Over the last few years, a new stream of research has emerged in the field of strategic management which focuses on the analysis of its microfoundations. This line of research analyzes strategic topics examining their foundations rooted in individual actions and interactions. The main purpose of this paper is to examine this emerging literature of microfoundations, indicating its usefulness and main characteristics. Through a systematic literature review, this paper contributes to the field by identifying the main areas studied, the benefits and potential of this approach, and some limitations and criticisms. Moreover, the paper studies how the integration of micro and macro aspects in strategy research may be carried out, examining several works that use a multilevel approach. Some methodological approaches that may help to effect this integration are indicated. These aspects will be analyzed in relation to the resource-based theory.

In the field of management and organizational sciences, specialization has led to a divide between the “macro” and “micro” areas (Aguinis et al., 2011). On the one hand, macro management research domains (for example, strategic management and organization theory) focus their research questions and analysis mainly on the organizational or firm level, and even on interorganizational relationships. On the other hand, micro areas (for example, organizational behavior and human resources management) examine research questions at levels within organizations, mainly individual and group levels, although some studies use the organizational level to analyze their questions.

Strategic management is considered to be a macro area. For example, the four main questions of strategy proposed by Rumelt et al. (1994) are related to the firm level. The present article focuses on one of these questions, namely, why firms are different, or in other words, what factors maintain performance heterogeneity among competitors in spite of competition and imitation. Strategy research tries to explain macro (firm) phenomena (typical dependent variables are firm performance or firm competitive advantages) on the basis of independent variables that are usually also collective firm variables (firm resources and capabilities, organizational routines).

However, over the last few years, some authors have emphasized the importance of understanding collective strategic issues and research questions taking into account aspects at the individual level as independent variables. The name of this research line is microfoundations of strategic management (Felin and Foss, 2005; Foss, 2010). This interest in micro issues is not exclusive to strategy but is part of a general process in the social sciences. Thus, several fields have also considered micro elements (for example, in economics several research lines have been developed, such as microeconomics and neuroeconomics, and in finance a line of behavior finance has also been developed).

We can follow researchers who are leading this emergent literature (Abell et al., 2008; Felin and Foss, 2005; Felin et al., 2012; Foss, 2010, 2011) in order to specify the foundations of microfoundations of strategy. Microfoundations research focuses on the influence of individual actions and interactions on firm heterogeneity. As indicated by Felin and Foss (2005, p. 441) in their seminal work: “Organizations are made up of individuals, and there is no organization without individuals. There is nothing quite as elementary; yet this elementary truth seems to have been lost in the increasing focus on structure, routines, capabilities, culture, institutions and various other collective conceptualizations in much of recent strategic organization research”. Therefore, the specific level of microfoundations is the individual level. Other issues located between individuals (micro) and firm (macro), such as organizational subunits, groups, teams or projects, may be considered as meso issues (Foss et al., 2010; Mathieu and Chen, 2011).

The main purpose of this paper is to examine the most relevant aspects of this emergent literature about microfoundations in strategy, carrying out a review of works published. Moreover, how micro and macro issues can be integrated in strategy research is analyzed, indicating some appropriate research methods that can facilitate this integration. These issues will be mainly studied with regard to the resource-based theory because this is the theory that has received most attention in microfoundations research, especially routines, capabilities and knowledge (Abell et al., 2008; Foss, 2010, 2011).

Several contributions of this article can be indicated. Firstly, through a systematic review of the microfoundations literature, this paper identifies the main areas and topics studied, the research methods used, the benefits, opportunities and potential of microfoundations to improve strategy research, and the main limitations, critiques and challenges that must be addressed. Secondly, this paper tries to reduce the divide between micro and macro research, suggesting ideas and methods that may help to implement micro–macro multilevel studies. This issue is relevant because the bridge across this macro–micro divide is considered as a key factor to help advance management research (Rynes, 2005).

The remainder of the article proceeds as follows. In the next section, the main characteristics of microfoundations in strategy are examined. Then a systematic literature review of microfoundations in the resource based theory is carried out, identifying studies published, examining main areas and topics, and analyzing the main opportunities, challenges and criticisms. Before the conclusions section, several issues with regard to the integration of micro and macro research are examined.

Microfoundations research in strategic managementStrategy research has usually been macro level in order to explain firm performance heterogeneity. Two important research lines in strategic management focus on this macro level. Firstly, some works have examined the determinants of firm performance (firm, industry and corporate effects, among others) and their relative importance (McGahan and Porter, 1997; Rumelt, 1991; Schmalensee, 1985). These studies are macro research as they analyze effects at firm or higher levels (strategic groups, industries, locations). Moreover, these effects are examined at an aggregated level. For example, the firm effect represents the firm's bundle of resources and capabilities, and no specific resource is analyzed. Secondly, other studies have examined the impact of specific resources on performance, but these works have analyzed resources at the firm level (firm resources, organizational routines) and not at an individual level (Armstrong and Shimizu, 2007; Crook et al., 2008; Newbert, 2007).

In addition, many topics of interest in strategic management, such as diversification patterns, vertical integration, competitive rivalry and so on are placed on a level of analysis that is above that of the individual (Abell et al., 2008). In fact, the dependent variables in strategic management are usually placed at the level of the firm, and the independent variables and the mechanisms that link them to the dependent variables are also usually considered at the firm level. Thus, organizations are considered as repositories of organizational routines, firm capabilities and organizational knowledge, and these routines, capabilities and knowledge are sources of competitive advantage, financial performance, innovation and the boundaries of companies.

A specific example is the analysis of knowledge as one of the main firm resources. The knowledge-based view of the firm advocates that the main sources of competitive advantage are knowledge assets that are built over time through processes of creating, integrating and sharing knowledge. Although some works highlight the importance of individual knowledge (Spender, 1996), the knowledge literature has been dominated by a macro orientation that considers constructs at the level of the firm (firm knowledge, firm absorptive capacity, etc.). However, processes of creating, integrating and sharing knowledge are critically dependent on the skills, efforts, knowledge and behaviors of individuals, often in response to rapidly changing contingencies (Foss, 2010).

The perspective in strategy of trying to explain dependent variables at the firm level (competitive advantage, firm performance) through independent variables that are also examined at this firm level (routines, capabilities) is not erroneous and, of course, it is legitimate. However, the specific gap and associated problem are that this macro or collectivist mode of explanation, which dominates large parts of the strategic management literature, is incomplete as individual actions and interactions (individual independent variables) may be relevant to the explanation of firm-level outcomes.

Felin and Foss (2006) and Foss (2011) point out some reasons for the macro bias in strategic management, or in other words, why microfoundations have taken so long to explicitly enter the research agenda of strategy scholars. One reason is that the lack of microfoundations in strategy is perhaps based on an implicit agreement that such discussions are best left at the level of the base disciplines (e.g., psychology at the individual level). That is, it can be argued that strategy is by definition a collective or firm-level discipline, and thus the key questions of interest should be pursued at this level, without consideration of other levels. Another reason is that it is arguable that there are pragmatic reasons rather than conscious neglect for microfoundations being somewhat sidetracked in the development of the strategic management field, reasons that turn on data collection costs, the need to learn unfamiliar statistical methods, and the sheer difficulty of theoretically linking micro and macro issues. Moreover, the empirically driven character of strategic management perhaps crowds out methodological, theoretical and philosophical inquiry related to the analysis of microfoundations.

However, there are several reasons why microfoundations are critical for strategy research (Abell et al., 2008; Foss, 2010, 2011).

Level of analysisA first issue is related to the appropriate level of analysis for strategic phenomena. In this regard, Foss (2010) provides an interesting example in competitive strategy. Consider the phenomenon of competitive interaction between firms. From a macro perspective, competitive interaction can be seen as constituted by the offensive and defensive actions of firms. However, those actions may be explicable in terms of the actions of individuals in those firms. Individuals make decisions, and several characteristics of these individuals (perceptions, emotions, cognitive aspects) may influence decision-making processes.

Often pragmatic considerations suggest that the relevant level for studying competitive interaction is the level of firms, while explanation directly in terms of individual decision-making is to be eschewed because it is too time-consuming. In any case, strategic management scholars should know that to say that a firm has a certain capability is essentially shorthand for a complex set of underlying individual actions and interactions, and associated characteristics or skills which make the realization of these capabilities possible (Abell et al., 2008; Foss, 2011). Thus, the collective behavior of a system (the firm) is the consequence of actions and interactions of its components (individuals). Because scholars may not always want to make explicit reference to complicated underlying patterns of individual actions, they often prefer to make use of explanatory shorthand in the form of collective concepts.

As noted by Felin and Foss (2005), organizations are made up of individuals, and there is no organization without individuals. Any theoretical and/or empirical effort to explain strategy phenomena (the explananda) has to make a choice that concerns the level at which explanation takes place, that is, the analytical level at which the important components of the explanans are located. In this regard, there has been an important philosophical and methodological debate for more than a hundred years in economics, sociology and the philosophy of science as to whether individuals or social collectives have explanatory primacy. This debate has raged under the label of methodological individualism versus methodological collectivism (Foss, 2010). On the one hand, in methodological collectivism, individuals are assumed to be homogeneous and randomly distributed; organizations exist prior to individual action; context and organization drive the behavior of individuals, that is, individuals are essentially extraneous and highly malleable by context and situation; and collective constructs are independent of the individuals. On the other hand, methodological individualists argue that collectives are inherently made up of and result because of heterogeneous individuals, and individuals should thus be the basic unit of analysis. From an ontological point of view, only individuals, and not collectives, are acting entities that may make decisions (Felin and Foss, 2005, 2006; Felin and Hesterly, 2007). Combining methodological individualism with an emphasis on causal mechanisms implies that strategic management should fundamentally be concerned about how intentional human action and interaction causally produce strategic phenomena (Abell et al., 2008).

Alternative explanationsA problem with a macro-level explanation is that there are likely to be many alternative lower level explanations of macro-level behavior that cannot be rejected with macro-analysis alone. Alternative explanations at lower levels are readily apparent in the capabilities view, which seeks the explanation of differential firm performance in firm-level heterogeneity, that is, heterogeneous routines and capabilities, when heterogeneity may be located at the individual level (Abell et al., 2008; Foss, 2010, 2011).

Managerial interventionOne of the main ideas that microfoundations emphasize is the fundamental mandate of strategic management: to enable managers to gain and sustain competitive advantage through their decisions and actions. To achieve this, managerial intervention is required, which inevitably has to take place at the micro level (Abell et al., 2008; Foss, 2010). A correlation between collective culture and collective outcomes tells the manager very little about what should be done to change culture. It makes little sense to argue that managers can directly intervene on the level of capabilities. However, managers can influence capabilities by hiring key employees or by changing human resources policies, all of which involve the micro level. The collectivist orientation underlying the capabilities approach provides a radical departure from the raison d’etre of strategic management, which ought to provide actionable and useful theoretical insights for the practicing manager. Microfoundations try to align with this key characteristic of strategy. The origins of collective concepts are likely to be at the individual level and ultimately to be rooted in purposeful and intentional action (Felin and Foss, 2005).

In summary, strategy research and practice in general, and research on the resource-based theory, can be improved through the application of a microfoundations approach. The main argument of microfoundations is that individuals matter, and this micro level is needed for explanation of collective strategic phenomena. As noted by Felin and Foss (2005), to fully explicate any strategic topic at an organizational level (capabilities, knowledge, learning, identity), one must fundamentally begin with and understand the individuals that compose the whole as the central actors, specifically their underlying nature, choices, abilities, propensities, heterogeneity, purposes, expectations and motivations.

The interest and attention devoted to microfoundations in strategy are growing. Within strategic management, the microfoundations project mainly focuses on the resource-based theory (capabilities, routines), and this line of microfoundations is considered by Barney et al. (2011) as one of the key themes for the future of this theory. Moreover, in the last few years, several special issues on microfoundations have been published in several journals. In 2011 the Strategic Management Journal published a special issue devoted to the psychological foundations of strategic management. Powell et al. (2011) pointed out that these psychological foundations are a key pillar to explain firm heterogeneity. In 2012, the Journal of Management Studies published a special issue on the micro-origins of organizational routines and capabilities. Felin et al. (2012) noted that microfoundations may help to advance research on organizational heterogeneity emphasizing the origins and development processes of capabilities and routines. In 2013 Academy of Management Perspectives also published a symposium focused on microfoundations. Devinney (2013) believes that microfoundations can be a key platform in moving the management field forward. In addition, a special conference of the Strategic Management Society will be held in 2014 in Copenhagen devoted to microfoundations for strategy research. Furthermore, the new Behavioral Strategy interest group in the Strategic Management Society tries to promote research that applies cognitive and social psychology to strategic management theory and practice.

Therefore, there are several indicators regarding the growing attention devoted to microfoundations in strategy research. An additional indicator is the high number of works on microfoundations that are being published. In the next section, a systematic literature review of these studies is carried out.

Literature review of microfoundations researchMicrofoundations in strategy can be considered, at the same time, as an “old” research line (or at least with antecedents for many years), and as a “new” or “emergent” line, due to its revitalization in the last few years. In this section, firstly the main antecedents of microfoundations are indicated. Secondly, from its revitalization and through a systematic literature review, the recent studies that focus on microfoundations of the resource-based theory are identified. Finally, the main opportunities, potential, challenges and critiques of microfoundations are examined.

Antecedents of microfoundations in strategy and the resource-based theoryAlthough there is a macro bias in strategy research, micro perspectives have also influenced the early development of strategic management and continues to influence this field through several streams of research and works that consider the individual level, particularly the role of managers. In fact, as noted by Hoskisson et al. (1999), the earlier works in strategy (Chandler, 1962; Ansoff, 1965; Learned et al., 1965; Andrews, 1971) have been influenced by earlier classics in management that analyzed internal processes, leadership, and the functions, key role and characteristics of managers (their behavior, cognition, motivations, etc.) (Barnard, 1938; Cyert and March, 1963; March and Simon, 1958; Penrose, 1959; Simon, 1945; Selznick, 1957).

Moreover, in the recent development of the field of strategic management, many streams of research are related to individual actions, internal processes and the role and characteristics of managers. For example, seminal works on a behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert and March, 1963; March and Simon, 1958) have been used to develop a behavioral strategy approach (Bromiley, 2005; Gavetti, 2012; Powell et al., 2011) that merges cognitive and social psychology with strategic management theory and practice. In the same way, an important aspect of strategy is related to how leaders make decisions and influence firm strategy and performance (Blettner et al., 2012). In this regard, the line of research about top management teams or upper echelons (Hambrick and Mason, 1984) analyzes the characteristics, role and influence of the general manager and top management teams in collective organizational variables. Moreover, some studies examine the emotions of managers (Delgado-García and De La Fuente-Sabaté, 2010; Nickerson and Zenger, 2008), the cognitive and psychological aspects that influence interpretations and perceptions of managers (Buyl et al., 2011; Eggers and Kaplan, 2013; Reger and Huff, 1993), and the role of motivations of employees together with the fit of individual and collective interests (Gottschalg and Zollo, 2007). In addition, the process school of strategy (Johnson, 1987) and the line known as strategy-as-practice (Vaara and Whittington, 2012) can also be considered as approaches that emphasize practices and actions at an individual level that influence the formulation and implementation of strategies.

In the resource-based theory, several works can also be considered as antecedents of microfoundations of this theory. For example, Coff (1997) focused on microfoundations of human assets (motivations, rationality or decision-making process). Coff (1999) and Lippman and Rumelt (2003a,b) used microfoundations to analyze the economic value of resources and their characteristics related to the creation and appropriation of economic rents. Foss (2003), in an analysis and critique of Nelson and Winter (1982), emphasized the absence of microfoundations and advocated its adoption in order to improve the power of explanation and prescription of organizational capabilities.

In summary, there are streams of research within the tradition of strategic management in general and in the resource-based theory in particular that are related to the microfoundations perspective and that could be considered as antecedents of this perspective and its emphasis on individual action and interaction. In this regard, Powell et al. (2011) point out that behavioral strategy is not a new idea, but they believe that the time has come for new beginnings. And Foss (2011) indicates that it is implicit in the call for microfoundations that existing work that touches on microfoundational issues (for example, top management teams, leadership, emergent strategies, or strategic human resource management) does not go far enough with respect to accounting for relevant microfoundations. Therefore, the recent calls for microfoundations and studies published in the last few years have this characteristic of newness, revitalization or new beginning as they explicitly emphasize the individual level as a key element in strategy research. In the next section, this emergent literature is examined.

As noted by Foss (2011), calls for microfoundations have seldom been made on the purely abstract level and have usually been tied to concrete strategic management issues, typically in the context of the resource-based theory. Consequently, the literature review focuses on the resource-based theory.

Review of emergent literature of microfoundations in the resource-based theoryAn important aspect to carrying out the search for studies is the beginning of this emergent approach of microfoundations. Foss, one of the main authors leading this approach, implicitly dates the start of this movement as 2005 in two articles (Foss, 2010, p. 12; Foss, 2011, p. 1414). The reason could be the publication in the journal Strategic Organization of a seminal article by Felin and Foss (2005). This work is devoted completely and explicitly to the analysis of microfoundations in strategy, and calls for the adoption of this approach in strategic management, providing the base ideas of this line of research, examining the main deficiencies of capabilities collectivism, and emphasizing the individual-level origins for organizational capabilities. Moreover, this work is considered by Winter (2013) as the opening salvo of microfoundations.1

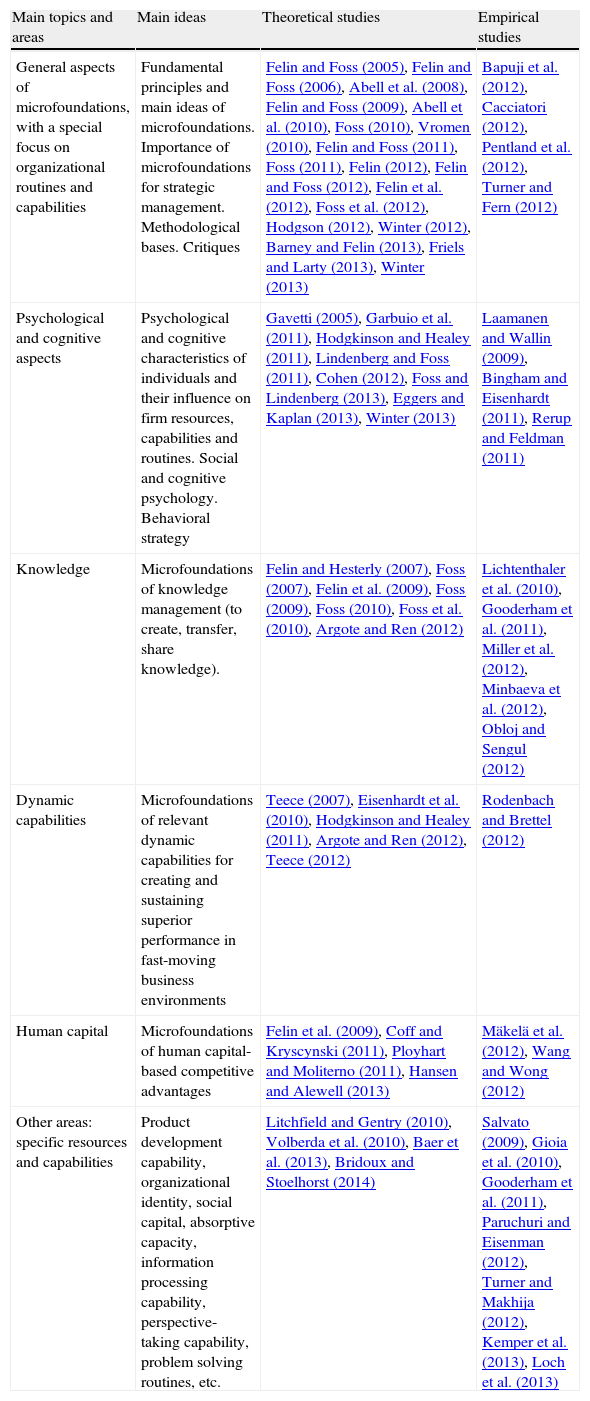

Table 1 shows the main studies on microfoundations in the resource-based theory published from 2005. In order to identify these works, a search was made in the main journals that publish strategy articles, both strategy journals (Strategic Management Journal and Strategic Organization) and general journals (Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Academy of Management Annals, Academy of Management Perspectives, Journal of Management, Organization Science, Journal of Management Studies and Administrative Science Quarterly). Moreover, a search of studies by the authors that are leading this approach, Teppo Felin and Nicolai Foss, was also made. In addition, studies that according to ISI Web of Knowledge have cited the seminal work by Felin and Foss (2005) were also reviewed. The references lists of studies identified were read in order to find other works. Several studies were found that had been published in other journals.

Studies about microfoundations in the resource-based theory.

Note: Some works related to several areas are included in all these areas.

In order to consider a work, the article title, abstract or keywords must contain some terms related to “micro” (microfoundations, micro-foundations, micro-level, micro-origins, etc.). Therefore, selected articles must focus explicitly on microfoundations as some of these three important parts of the article included these terms.2 This criterion can be considered as a limitation of the search strategy as some studies could not be identified, but we wanted to consider only those works that clearly analyzed some topic of microfoundations and this aspect was explicitly indicated from the beginning of the study. All articles identified were read and reviewed to check whether they analyzed some topic of the resource-based theory and the microfoundations approach was related to individual actions and interactions. In the end, 62 articles satisfied the search criteria. Table 1 shows these studies classified by the topic examined, distinguishing between theoretical and empirical articles.

Over the last decade, most articles have been published in recent years: in the first five years (2005–2009) only 12 studies (19%) were published, and since 2010 the remaining 50 articles were published (81%). Moreover, 23 journals were identified, and 6 journals have published three or more studies: Journal of Management Studies (16 articles), Organization Science (6 articles), Strategic Management Journal (6 articles), Academy of Management Review (3 articles), Journal of Management (3 articles) and Academy of Management Perspectives (3 articles).

Regarding the type of article, papers have been classified as theoretical or empirical articles. Most manuscripts are theoretical (40 articles, 65%). Only 22 articles are empirical (35%), and the methodologies used are diverse in this group. Specifically, some studies have used quantitative methods (14 articles, 64%), for example, experiments, simulations and questionnaires, carrying out statistical analysis, mainly regression analysis and structural equation modeling. Other works have employed qualitative methods (6 articles, 27%), mainly case studies. Finally, 2 articles (9%) combine quantitative and qualitative methods.

With regard to the main areas and topics studied, some works analyze general issues of microfoundations, with discussion and theoretical insights about what microfoundations are, why strategy and the resource-based theory need them, and which are the methodological bases that justify their analysis (issues examined previously in this article). Most of these works focus specifically on capabilities and routines in general. Some exemplars in this group are Felin and Foss (2005, 2006, 2009, 2011), Abell et al. (2008, 2010) and Foss (2011).

The analysis of psychological and cognitive issues is another relevant research area within microfoundations. Gavetti (2005) examines the development of firm capabilities based on cognitive characteristics of individuals. Powell et al. (2011) provide ideas about behavioral strategy emphasizing that this approach merges cognitive and social psychology with strategic management. Hodgkinson and Healey (2011) examine the psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities. Garbuio et al. (2011) also analyze the psychological influences on the resource-based theory, specifically on structuring a firm's portfolio of resources. Other important studies in this group are Eggers and Kaplan (2013) and Winter (2013).

Several works have also focused on the knowledge-based view of the firm. For example, Felin and Hesterly (2007) point out that extant knowledge-based research largely focuses on collectives as the source of new value or the locus of knowledge (knowledge lies at the firm level). However, they challenge this conceptualization and theoretically build toward more individualist foundations, emphasizing that nested (individual-level) heterogeneity may provide a better explanation of collective heterogeneity. Moreover, a few individuals usually play a key role in processes of creating and sharing knowledge and in innovation outcomes. Other studies that also focus on knowledge issues are Foss (2009, 2010), Foss et al. (2010), Minbaeva et al. (2012) and Obloj and Sengul (2012).

Another important area is related to dynamic capabilities. For example, Teece (2007) analyzed several dynamic capabilities that are relevant for creating and sustaining superior performance in fast-moving business environments. These capabilities are based on individuals, and this author examined the characteristics and behaviors of these individuals. Other works that study the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities are Eisenhardt et al. (2010), Hodgkinson and Healey (2011), Argote and Ren (2012), Rodenbach and Brettel (2012) and Teece (2012).

Microfoundations of strategy have also focused on human capital. Coff and Kryscynski (2011) examine the microfoundations of human capital-based competitive advantages, identifying individual- and firm-level components that interact to grant some firms unique capabilities in attracting, retaining, and motivating human capital. Ployhart and Moliterno (2011) define human capital as a unit-level resource that is created from the emergence of individuals’ knowledge, skills, abilities or other characteristics. These authors offer a new approach to the conceptualization of the human capital resource by developing a multilevel model connecting micro, intermediate and macro levels. Other studies about microfoundations and human capital are Wang and Wong (2012) and Hansen and Alewell (2013).

Along with the previous areas and topics, some works have studied specific resources and capabilities, such as product development capability (Salvato, 2009), organizational identity (Gioia et al., 2010), social capital (Kemper et al., 2013), absorptive capacity (Volberda et al., 2010), information processing capability (Turner and Makhija, 2012), strategic problem formulation capability (Baer et al., 2013), perspective-taking capability (Litchfield and Gentry, 2010) and problem solving routines (Loch et al., 2013).

Finally, some authors consider that there are two main approaches to microfoundations (Foss and Lindenberg, 2013; Molloy et al., 2011). Traditionally, microfoundations in strategy have been examined from an economic perspective (Abell et al., 2008; Lippman and Rumelt, 2003a), and recently a psychological perspective linked to behavioral strategy has also been used (Powell et al., 2011).

Opportunities, challenges and criticismsBased on the literature review, three important aspects of microfoundations are examined in this section: first, their potential and main opportunities for improving strategy research; second, the challenges and barriers that must be overcome to advance the microfoundations project; and third, the main criticisms received.

Regarding potential and opportunities, the resource-based theory helped and is helping to open the black box of the firm. Microfoundations may contribute and may help to advance in this important purpose, shedding light on internal elements, processes, and individual actions and interactions as a source of firm heterogeneity. In this regard, some research questions linked to microfoundations can be indicated: what is the relative importance and influence of individual versus collective variables on firm performance?; what are the micro-origins of organizational capabilities, competitive advantage and firm performance?; how do individual characteristics scale to collective variables?, how do collective capabilities emerge through social processes of aggregation and interaction of individual variables?; what are the cognitive and motivational antecedents of individual and collective learning and the development of organizational capabilities?; or how do initial conditions at firm and institutional levels influence individuals actions and learning processes? In summary, an important potential and opportunity of microfoundations is to ask, analyze and answer relevant research questions related to the explanation of firm heterogeneity.

In addition, as noted in some previous questions, another opportunity is the development and consolidation of multilevel research in strategy inquiry. Microfoundations of strategy inherently involve at least two levels of analysis: the macro level (firm), as dependent variables in strategic management are usually studied at this firm level, and the micro level (individual) that is examined by microfoundations. Given the importance of this potential, the next section is devoted to micro–macro multilevel research.

Furthermore, along with the resource-based theory, other topics that can be favored by the microfoundations lens and by a micro–macro multilevel approach are (Buckley et al., 2011): top management teams, executive compensation, strategic human resources management, corporate social responsibility, social networks, organizational learning, decision making and entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, several challenges, obstacles and barriers to the development and advancement of microfoundations can be indicated. Micro–macro multilevel research is more difficult than micro research or macro research, as more time, effort, knowledge and research capacities are needed. Thus, a researcher needs to know both micro and macro theories and how to combine them. And the integration of micro and macro issues may require appropriate methodologies that are different from methodologies used to analyze strategic issues at a macro level. In the next section, several methodologies that can be employed in micro–macro multilevel research are examined.

In addition, doctoral training of new researchers often does not foster a sufficient understanding of micro and macro aspects. Students now feel obliged to choose an area of specialization as soon as possible so they can begin developing a pipeline of research as soon as possible. Many doctoral programs do not require micro or macro students to take a doctoral seminar in a strategy or organizational behavior seminar (in a “competing” discipline), respectively. Furthermore, there are risks associated with trying to publish cross-disciplinary multilevel research that include micro and macro issues. For example, a strategy researcher integrating motivational or psychological theories may be unsure how the reviewers at a strategy-oriented journal will receive and evaluate this type of work (Buckley et al., 2011). These barriers may explain why there are so few empirical studies carried out using a micro–macro multilevel approach.

Finally, the microfoundations project is also receiving some criticism. Winter (2012) examines the origins of organizational capabilities. He argues that an adequate answer to the origins question must fully respect the element of time, emphasizing that we will not benefit much from an ‘individuals first’ account of origins that has no convenient place for the intrinsic connection to the element of time. The study of origins of capabilities is primarily a study of transition mechanisms between ancestors and descendants, and it merges continuously into the study of incremental change of existing capabilities. Moreover, all individuals in a firm are not equally relevant for determining and explaining firm performance and strategic decisions. Floyd and Sputtek (2011) indicate that it is necessary to identify the relevant individuals, an issue that is also considered by Felin and Hesterly (2007), Mollick (2012) and Aguinis and O’Boyle (2014).

In addition, Hodgson (2012) points out that authors who stress the need to build microfoundations rooted in individual action and interaction consistently ignore some ambiguities and problems. For example, a key statement of the microfoundations project is that organizations are made up of individuals and there is no organization without individuals (Felin and Foss, 2005). Another proposition is that combining methodological individualism with an emphasis on causal mechanisms implies that strategic management should fundamentally be concerned with how intentional human action causally produces strategic phenomena (Abell et al., 2008). Hodgson (2012) agrees with these statements, but he indicates that organizations are more than individuals as organizations involve social relations, emphasizing that there is no organization without social relations. Moreover, we are also required to explain the causes behind individual actions and intentions. In this regard, collective variables (organizational routines, structure and culture) may help to explain these individual characteristics. Therefore, causation runs both ways between the individual level and macro level phenomena. Jepperson and Meyer (2011) also indicate that methodological individualism has limitations. In summary, both individual characteristics and social/collective relations and aggregation processes are essential to understand and explain collective strategic phenomena and their emergence. Barney and Felin (2013), Kozlowski and Klein (2000) and Kozlowski et al. (2013) also emphasize this idea.

In conclusion, it is our opinion of the debate between methodological individualism and collectivism that the issue is not necessarily be methodological individualism (micro) versus methodological collectivism (macro) but rather it could be how to combine the strengths of each through a micro–macro integration recognizing their complementarity. Therefore, the criticism related to the excessive emphasis of microfoundations on methodological individualism suggests the need to consider jointly macro and micro aspects, examining their reciprocal influences.

Hoskisson et al. (1999) used the idea of the swings of a pendulum to analyze the development and evolution of the field of strategic management since its inception. They analyzed this evolution and theoretical contributions using two extremes of the pendulum: the attention to internal firm characteristics or the attention to external environment. A new pendulum can be specifically employed for examining the resource-based theory, taking into account micro and macro levels as the two extremes. In this regard, although this theory has mainly emphasized the macro level, the microfoundations project shifts attention toward micro issues. As collective/macro phenomena and variables are also relevant, in our opinion the desirable and appropriate situation in this pendulum would be an intermediate position that highlights the relevance and need of integrating macro and micro levels. This idea is examined in the next section.

Micro–macro integration in strategy and in the resource-based theoryAs noted previously, the field of management and organizational sciences stays/remains traditionally divided between micro and macro areas. This divide is reflected in the specialization of researchers in either micro or macro domains. This divide is further reflected by the preference for researchers to publish in either macro or micro journals. Evidence of this divide is also reflected by the sometimes divergent research design, measurement and data analysis techniques used across these domains (Aguinis et al., 2011). This divide is considered to be a weakness of management that must be overcome and then the integration of micro and macro aspects is considered as a key issue in the development of the field (Aguinis et al., 2011; Rynes, 2005) that can help to solve another important problem, namely, the science-practice gap. An integration of micro and macro aspects combining different levels of theory and analysis may provide a better understanding of strategic issues and questions, and be more interesting and useful for companies and their managers.

Integration of micro and macro issues is related to multilevel research (Dansereau et al., 1999; Hitt et al., 2007; Klein and Kozlowski, 2000). Some authors encourage researchers to carry out studies based on multitheoretical and multilevel approaches (Chen et al., 2005; Hofmann, 2002). The integration of micro and macro issues is a particular case of multilevel research, as some multilevel research does not consider micro and macro aspects. For example, the main methodologists in multilevel research are micro scholars (organizational behavior, industrial–organizational psychology) who have studied relationships between the micro level (individuals) and the meso level (groups, teams). The emergence of and growing attention to microfoundations in strategy inherently implies the integration of micro and macro issues, as the main dependent variable in this field is usually a macro variable (for example, firm performance or firm competitive advantages) and independent variables may be macro and micro variables. Several different relationships can be examined between these micro and macro variables (direct, mediating and moderating relationships). Therefore, a key aspect in multilevel research in strategy is to determine the relationships between micro and macro variables (Foss, 2010).

The purpose of this section is not to carry out a systematic literature review of micro–macro multilevel research in strategy, but we would like to indicate some works that consider the integration of these levels. Gavetti (2005) examines the development process of firm capabilities based on cognitive characteristics of individuals and the key role of organizational routines. Teece (2007) also considers that dynamic capabilities are based on both individual and organizational aspects. For example, the capability for sensing opportunities and threats can be developed and improved through both the cognitive and creative capacities of individuals and some organizational processes such as research and development activities. Then, an adequate integration of these individual and organizational elements strengthens this capability. Salvato and Rerup (2011) also emphasize the importance of multilevel research to examine organizational routines and capabilities. Specifically, these authors integrate three levels (firm, group and individual levels) in order to explain firm performance and the emergence of organizational routines and capabilities through the behavior and cognitive capacities of individuals.

In the area of human capital, Coff and Kryscynski (2011) highlight that a key aspect to create value and competitive advantages through human capital is the integration and interaction of the individual level (micro) and the organizational systems of human resources management (macro). These authors point out that the combination of idiosyncratic individuals and organizational systems for attracting, retaining and motivating talented employees may be among the most powerful isolating mechanism that can reduce imitation by competitors. Ployhart and Moliterno (2011) propose a multilevel model to analyze the emergence of human capital as a firm resource connecting micro, intermediate and macro levels. There are three main parts in this model. First, from the field of psychology, the origins and sources of human capital are cognitive (general cognitive ability, skills, experience) and non-cognitive (personality, interests) characteristics at the individual level. Second, these individual characteristics are combined and amplified through interaction processes at group and team level. Third, human capital as a firm collective resource emerges through these processes.

In the knowledge area, Foss (2009) also indicated the relevance of multilevel studies. Regarding the knowledge sharing process, Foss et al. (2010) propose a model of relationships between micro and macro levels (macro–macro, macro–micro, micro–micro and micro–macro) that they use in their literature review on this topic.

Payne et al. (2011) carry out a literature review about capital social research, indicating that most studies focus only on one level. These authors encourage multilevel research both to micro and macro scholars, proposing suggestions and opportunities derived from the integration of micro and macro issues.

In their article about the future of the resource-based theory, Barney et al. (2011) identify sustainability and corporate social responsibility as essential key future themes in this theory. In this regard, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) examine three levels of analysis: institutional, organizational and individual. For these three levels, and for a through literature review, the authors identify variables that may predict the level and initiatives of corporate social responsibility, and they also identify mediators and moderators of corporate social responsibility–outcomes relationships. These authors propose a multilevel and multidisciplinary model, emphasizing the relevance of multilevel research that integrates micro and macro aspects.

Mollick (2012) points out that performance differences between firms are generally attributed to organizational factors rather than to differences among the individuals who make up firms. Consequently, little is known about the part that individual firm members play in explaining the variance in performance among firms. In this work, the author employs a multiple membership cross-classified multilevel model to test the degree to which organizational and individual factors explain firm performance. The results indicate that variation among individuals matter far more in firm performance than is generally assumed.

Finally, micro–macro multilevel research poses a challenge regarding research designs and methodologies. Next, some methodologies that can be used in this type of multilevel research are briefly examined. From a quantitative approach, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) can help to overcome some limitations of traditional regression analysis when examining factors that determine firm performance. Specifically, HLM takes into account that these factors can be located at different levels and that the relationships between these levels may be of a nested nature (Hofmann, 1997). HLM is now the main statistical technique that is used in research about the relative importance of determinants of firm performance (for example, analysis of firm, industry and corporation effects). Hough (2006) and Misangyi et al. (2006) emphasize that previous works used statistical techniques that consider variables as independent, but actually the relationship is of a nested nature (firms are nested within both industries and corporations). Similarly, in micro–macro multilevel research, there is this nested relationship as firms (macro) are made up of individuals (micro), or in other words, individuals are nested within firms. Therefore, HLM3 overcomes this problem of non-independence (Mathieu and Chen, 2011).

Along with quantitative methods, the use of qualitative methods can also contribute to the advance of the microfoundations project and to micro–macro multilevel research. A relevant theme in this type of research is how individual actions and characteristics aggregate through some processes to create and develop collective phenomena, or in other words, how these collective variables emerge through a process of aggregation of individual variables (for example, how organizational routines and dynamic capabilities are created and developed from aggregation of individual actions and interactions). A detailed, in-depth and longitudinal analysis of these processes may be carried out through qualitative research (Mathieu and Chen, 2011).

Mixed methods research (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010), that is, the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods in the same study, can also contribute to micro–macro multilevel research. For example, the quantitative part could analyze the influence of micro variables (for example, cognitive and psychological characteristics of individuals) and macro variables (for example, organizational routines and capabilities) on firm performance using HLM. And the qualitative part could examine the emergence process of these organizational capabilities from individual characteristics. Therefore, such works would combine in the same study outcomes- and process-research. Powell et al. (2011) point out that as behavioral strategy expands and develop, the benefits of methodological pluralism will become increasingly apparent, seeing mixed methods research as the future of this strategy approach.

ConclusionsThe microfoundations project is quickly becoming an important research domain in strategic management in general and in the resource-based theory in particular. This resource-based theory has helped to open the black box of the firm and to understand and determine the sources of competitive advantage. In this regard, microfoundations can help to shed more light examining individual actions and interactions. The literature review has identified as the main areas studied the fundamental principles of microfoundations, psychological and cognitive aspects, knowledge, dynamic capabilities and human capital.

In our opinion, two important aspects in the future of microfoundations in strategy are multilevel research and aggregation processes. First, multilevel research can help to analyze influences and relationships between micro and macro variables. For example, how collective variables influence individual variables, how variables at the individual level influence firm collective phenomena, how both individual and collective variables influence the key dependent variables in strategy (performance, profitability, competitive advantage, firm boundaries, level of diversification and internationalization, etc.), and mediating and moderating relationships between micro and macro variables. Second, another relevant topic is the analysis of how individual actions and factors aggregate through social processes to create and develop collective strategic phenomena (organizational capabilities and routines), or in other words, how these collective variables emerge through transformation and aggregation processes of individual variables.

The microfoundations project must overcome some challenges and critiques derived from an excessive reductionism. Addressing these challenges and critiques, in our opinion microfoundations can help to improve and advance strategy research through four main aspects: first, defining and analyzing innovative, interesting and relevant research questions, and developing theory; second, improving research methods encouraging the use of appropriate quantitative and qualitative methods; third, bridging the micro–macro gap; and fourth, bridging the research-practice gap. Regarding this fourth point, we would like to emphasize that the microfoundations project highlights the analysis of research problems and questions connected to management practice, as both micro and macro aspects take part in actions and decisions made by companies when strategies are formulated and implemented. Therefore, microfoundations and micro–macro multilevel research can help to bridge this important gap between research and practice. There are important conceptual, theoretical and methodological challenges, but microfoundations can help to improve both the rigor of our research works and the implications for practice of our studies.

As noted previously, a limitation of this paper is the search strategy used to identify the studies about microfoundations in the resource-based theory that are included in Table 1. Moreover, a systematic literature review of micro–macro multilevel research in strategy has not been made, and then an interesting future research could be to carry out this literature review in order to determine the areas and research questions examined, the relationships between these two levels, the methods used, how to implement this type of multilevel research, and the main difficulties and problems that must be considered.

I would like to thank the guest editors of this special issue for their suggestions; in this regard, I am especially grateful to Luis Ángel Guerras-Martín. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. This paper has benefited from their interesting and relevant ideas and suggestions.

Felin and Foss (2005) had received 104 citations until August 2013, according to ISI Web of Knowledge.

Some exceptions were considered: Felin and Foss (2011) do not use any term “micro” in title, abstract or keywords, but it focuses clearly on microfoundations; two articles published in the special issue on psychological foundations in Strategic Management Journal, as these two studies focus on capabilities (Bingham and Eisenhardt, 2011; Hodgkinson and Healey, 2011); Garbuio et al. (2011) published in the special issue of the resource-based theory in the Journal of Management as the guest editors Barney et al. (2011) consider that this article is about microfoundations; and three articles published in the special issue of the Journal of Management Studies (Cacciatori, 2012; Miller et al., 2012; Wang and Wong, 2012) as this special issue focuses on microfoundations of organizational capabilities and routines.

The main ideas about the application of hierarchical linear models can be examined in Bryk and Raudenbush (1992), Hofmann (1997) and Hofmann et al. (2000).