This study delves in the controversy about the nature and the sign of the effect of interorganizational relationships on entrepreneurial orientation. The paper analyses the effects of networks of interorganizational relationships at firm level. Specifically, we study the influence of closure of interorganizational relationships in entrepreneurial orientation and the mediating role of dynamic capabilities. The empirical analysis was developed on a sample of 292 Spanish agri-food firms. We detect a positive mediating effect of the closure of interorganizational relationships, mainly cooperative relationships, on entrepreneurial orientation through dynamic capabilities. It highlights the emergence of a suppression effect uncovering the dark side of closed interorganizational relationships in several dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation – proactiveness, autonomy and risk-taking –. This paper contributes to link three theoretical approaches – social capital, entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities – to probe further into the implications of interorganizational relationships.

Recently, interorganizational relationships (IRs)1 have received increasing interest in the field of management (Barringer and Harrison, 2000; Barroso-Méndez et al., 2015; Majchrzak et al., 2015). Literature studies have looked at whether or not IRs make sense and whether the advantages outweigh the disadvantages from different theoretical perspectives (Barringer and Harrison, 2000). In this body of literature, research about the networks of IRs from the social capital theory has received increasing attention (Koka and Prescott, 2002; Zaheer et al., 2010; Bojica et al., 2012).

There are different approaches and divergent findings with respect to the consequences of IRs on strategic behaviour and firm's performance. Specifically, we find relevant disagreements about the nature and signs of the effect of closure of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation (Wu et al., 2008). Closure encompasses the whole social interaction within the firm's network and includes density and strength of the IRs (Coleman, 1990; Zaheer et al., 2010). Thus, “a network with complete closure is one in which all actors are connected to one another” (Zaheer et al., 2010: 67). The closure of IRs, is the most controversial aspect of social capital, because it creates network paradoxes, providing opportunities to obtain tacit knowledge, valuable ideas and new opportunities, but also involving restrictions in detecting and accessing new ideas due to myopia, inertia and lock-in (Hakansson and Ford, 2002), affecting the firm's entrepreneurial orientation (Inkpen and Tsang, 2005; Bojica et al., 2012). Thus, the literature suggests that closure of IRs can yield both costs and benefits to entrepreneurial orientation, but we find a gap requiring resolution as to why these divergent effects emerge.

Entrepreneurial orientation is reflected in the implementation process of business initiatives and corporate culture (Dess and Lumpkin, 2005) and it is a key factor in obtaining a greater performance through differentiation, the development of better solutions ahead of competitors, enhancing adaptation to environmental changes and market trends and weakening the ability of rivals to compete and respond to actions in the future (Hughes and Morgan, 2007). Previous studies that have analyzed the relationship of closure of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation and performance show ambiguous results and are often divergent – positive, negative, U-inverted, non-significant – (Lee and Sukoco, 2007). Several researchers demand new studies that detect which factors explain why a positive or negative effect of closure of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation is generated. We propose answering these questions by analysing the mediating role of dynamic capabilities, because firms require mechanisms for exploring and exploiting the external knowledge derived from closure of IRs to develop an entrepreneurial orientation and dynamic capabilities can play this role.

Recently, literature relating to dynamic capabilities has been strengthened. Teece et al. (1997:516) define dynamic capabilities as the “firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments”. Thus, the development of dynamic capabilities determines the firm's business strategy (Teece et al., 1997), leading firms to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage (Shamsie et al., 2009). In this sense, we suggest that dynamic capabilities are a key element to connect closure of IRs and entrepreneurial orientation. On the one hand, previous literature has suggested that the firm's strategic orientation will depend on its developed capabilities (Kyrgidou and Spyropoulou, 2013). On the other hand, closure of IRs connects the firm with its environment, being a key factor for the development of socially constructed capabilities (Schoemaker and Jonker, 2005). Thus, dense and strong IRs develop certain mechanisms that transform external knowledge into internal capabilities and can be used in the development of new processes, products or services (Zahra and George, 2002). Therefore, we propose that closed IRs lead firms to develop an entrepreneurial orientation, only if they are oriented to create and strengthen their dynamic capabilities.

The empirical analysis was conducted on a sample of firms in the Spanish agri-food industry. Several studies have highlighted the role of IR closure in the success and entrepreneurial behaviour of firms in this industry (i.e. Mason and Gos, 2014; Tudisca et al., 2014). In other traditional sectors, Parra-Requena et al. (2015) observe that IRs are a key determinant of firms’ innovativeness. We can find in the agri-food sector examples of these relationships such as the SIRO2 group, which due to the high cohesion with both suppliers and customers has got a strong development of its dynamic capabilities, enabling it to continuously detect changes in consumer preferences, recognition and incorporation of valuable external information for the company as well as a high capacity for innovation. As a consequence, the company has a higher entrepreneurial orientation, which along with its proactiveness and innovativeness has enabled it to get ahead of its competitors.

In short, we contribute to filling in the gap identified in the literature, by exploring the controversial connection between closure of IRs and firm's entrepreneurial orientation. To this end, we study the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities to explain the relationship between closure of IRs and firm's entrepreneurial orientation.

Therefore, the main contribution of the paper is to advance the understanding of the controversial consequences of closed IRs on firm's entrepreneurial orientation, delving into the leading role of generation and development of dynamic capabilities. Secondly, in this paper we analyze the network of IRs measured through their closure, which is characterized by the predominance of cooperation against competition between agents (Bojica et al., 2012). Finally, an important conceptual contribution of this paper is the linking together of three theoretical approaches to study the consequences of IRs – social capital, entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities –, which have previously been poorly addressed in the literature as a group.

This paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we explain the theory framework and the derived hypotheses. Then, we describe the methodology used, followed by the obtained results. Finally, we present the discussion and conclusions of the study.

Theory and hypothesesClosure of interorganizational relationshipsDuring the preceding decades, interest in the use of social capital theory to study IRs has grown, based on the potential benefits derived from a firm's positioning in a network of IRs. These networks provide value to the firms immersed in them, allowing them to take advantage of the resources established in their relationships (Bourdieu, 1986). IRs of the firm's network developed over time, provide the basis for cooperation and collective action of the actors (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). The main aim of firms when they establish different IRs is the cooperation between them and the positive outcomes of these collaborations. Thus, social capital is identified as an essential element, allowing these firms to get a competitive advantage (Zaheer et al., 2010). Thereby, taking our lead from Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), we define social capital as the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of IRs possessed by a firm.

Widen-Wulff and Ginman (2004) consider that social capital is a complex concept, difficult to measure and value. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) distinguish three social capital dimensions: structural, relational and cognitive. The structural dimension of social capital highlights the implications of several structural characteristics of the network of IRs, especially its density and strength (Bojica et al., 2012). Foremost, density and strength of IRs have generated heated discussion on both the advantages and disadvantages of such, and secondly, because structural dimension has strong implications for the detection and exploitation of new opportunities through entrepreneurial actions. Zaheer et al. (2010) highlight structural dimension at the firm level, in terms of analysis, in the study of IRs, paying attention not only to the characteristics of each IR per se, but also to the structure of IRs surrounding the organization. From this point of focus, the authors refer to closure of IRs (Coleman, 1990), which in turn refers to density and strength, as opposed to structural holes (Burt, 1992). Both concepts are related to the social capital perspective of Koka and Prescott (2002), which draw differences between information richness, as result of closure of IRs, and information diversity, as result of structural holes.

The controversy arises when closed IRs allow the achievement of certain advantages that would be difficult to obtain in its absence (Coleman, 1990). Those firms with closed IRs, based on a high density of their network of IRs and a high strength of their ties, benefit from the coordination provided by the social norms of the network, which limit opportunism and facilitate cooperation, trust and exchange of valuable information (Zaheer et al., 2010). In such instances IRs are more likely to develop a collective action (Wasko and Faraj, 2005). However, although closed IRs can benefit the firm in many ways, they can also restrict the firm's ability to abandon existing technologies and practices, and engage in creative processes (Hakansson and Ford, 2002). These types of IRs often cause redundancy problems in the information exchanged (Koka and Prescott, 2002) and it can lead to a situation of blindness or myopia, because firms pay little attention to competitors outside the network (Inkpen and Tsang, 2005).

Entrepreneurial orientationCovin and Lumpkin (2011) note that research into firms’ entrepreneurial orientation completes a significant gap in the field of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurial orientation is a key construct for understanding how and why certain firms are able to renovate themselves through new growth trajectories (Morris et al., 2011). We consider entrepreneurial orientation as the generation process of entrepreneurial strategy that managers use to make decisions by disseminating organizational purposes, maintaining vision and creating sustainable competitive advantages (Rauch et al., 2009).

Previous researchers who have analyzed entrepreneurial orientation propose several dimensions that form this construct. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) incorporate two additional dimensions, that can be found within the entrepreneurial process, to the initial proposal realized by Covin and Slevin (1989). Innovativeness is the firm's propensity or willingness to support new ideas, novelty, creativity, experimentation and the creative process that results in new products, services or technological processes (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Proactiveness represents a future perspective where firms try to improve the current products or develop new products, anticipating changes and opportunities that appear in the environment, promoting changes in tactics and detecting future market trends (Hughes and Morgan, 2007). Risk-taking is defined as the willingness of a firm to take advantage of opportunities although the likelihood of success is unknown, acting bravely without understanding the consequences (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Competitive aggressiveness refers to the firm's propensity to challenge its competitors directly and intensely, achieving entry to or improvement of their position in the industry (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Autonomy represents the independent individual action or team activity, supporting an idea or vision and bringing it to completion in a self-directed process (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Following Lumpkin and Dess (1996), we incorporate the two additional dimensions, since they provide greater value and explanatory depth to the entrepreneurial orientation concept. On the one hand, Lumpkin and Dess (2001) reinforce the importance of competitive aggressiveness, demonstrating that it is an aspect of entrepreneurial orientation that must be considered. On the other hand, Burgelman (2001) emphasizes that autonomy, connected with the independent spirit, is another key aspect that characterizes the firm's entrepreneurial orientation.

There is a broad discussion in the literature about unidimensionality or multidimensionality of entrepreneurial orientation (Wales et al., 2013). De Clercq et al. (2013) analyze two conceptualizations of firms’ entrepreneurial orientation, the multidimensional approach and the composite dimension approach, and conclude that neither approach is intrinsically superior and both are compatible with the other. Following on from this, we combine both approaches, defining and contrasting a general hypothesis for entrepreneurial orientation as a composite dimension and, complementarily, one sub-hypothesis for each of five dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (Covin et al., 2006).

The entrepreneurial orientation research focuses mainly on the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship, showing that the development of an entrepreneurial orientation leads firms to obtain a greater sustained performance over time (Rauch et al., 2009; Engelen et al., 2014; among others), but also detecting negative, curvilinear (U-inverted) and contingent effects (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996; Rauch et al., 2009; García-Villaverde et al., 2013). However, the studies that analyze the antecedents of the firm's entrepreneurial orientation are scarce and its origins as an organizational phenomenon remain uncertain (Wales et al., 2013). According to Wales et al. (2013), it is necessary to delve into how other less analyzed factors determine the firm's entrepreneurial orientation. Thus, contrary to those studies that have focused on the external or internal variables, we propose dealing, on the one hand, with the IRs as a key factor linking the company with the environment, providing relevant information about changes and opportunities that occur in it. On the other hand, we focus on dynamic capabilities, which are built with the knowledge acquired through the IRs (Schoemaker and Jonker, 2005) and support the development of entrepreneurial orientation, generating new products, processes or services (Zahra and George, 2002).

Closure of interorganizational relationships and entrepreneurial orientationAnderson et al. (2007) suggest that an entrepreneurial process occurs through social relationships, social interaction and networks. Closure of IRs is regarded as a key aspect for the development of entrepreneurial behaviour and activities. It promotes a cooperation that allows access to resources, markets and technologies, and facilitates new combinations of resources (Bojica et al., 2012). Therefore, the closure of IRs owned by a firm favours its entrepreneurial orientation. In one way, it facilitates the exploitation of innovative opportunities with uncertain results (Perry-Smith and Shalley, 2003). Alternatively, it improves the ability to identify potential information asymmetries (Hargadon, 2002). In this way, we can find some examples from agribusiness that highlight the positive effect of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation such as Mason and Gos (2014) and Tudisca et al. (2014).

Focusing on each dimension of entrepreneurial orientation, it can be seen that closed IRs allow a rapid information flow, determining the firm's innovativeness (Kaasa, 2009). These dense and strong IRs provide access to new knowledge and lead to increases in efficiency and productivity of the innovation process. Thus, it was found that firms with closed IRs identify more opportunities to act proactively than independent entrepreneurs (Hills et al., 1997). Similarly, firms that have established IRs in a dense network usually have higher risk-taking behaviours. Larson (1992) states that the closer the interaction between the entrepreneurial firms and their network of IRs, the stronger the exchange of information that will favour the possibility of undertaking more aggressive actions against rivals. Also, these IRs allow a greater access to valuable resources and ideas that improve the firm's internal autonomy and to know and understand the practices and behaviours of other firms (Gnyawali and Madhavan, 2001).

However, several studies have detected problems related to the paradoxes of the network, derived mainly from the closure of IRs, which can counteract the impulse of the firm's entrepreneurial orientation. In this sense, firms with closed IRs have problems of redundancy and information obsolescence, myopia and inertia (Inkpen and Tsang, 2005), discouraging the development of an entrepreneurial orientation. Although most of the studies suggest a net positive effect of IR closure on entrepreneurial orientation and its dimensions (Bojica et al., 2012), the heterogeneity of arguments and empirical evidences demand new studies that explain when and how closure of IRs drives to entrepreneurial orientation.

The mediating role of dynamic capabilitiesThe ambiguous arguments and contradictory results of the previous empirical analysis demand more studies that incorporate new factors to further elucidate the effects of closure of IRs on firms’ entrepreneurial orientation. In this regard, we believe that many of the studies that have analyzed this relationship have gained an alleged positive effect because they don’t consider intermediate variables that enable a better understanding of the true effect of the closure of IRs in the entrepreneurial orientation. We believe that in order to generate entrepreneurial orientation from high levels of density and strength in the IRs, firms must be channelled properly. Specifically, we believe that the dynamic capabilities can exert a key mediator role in this relationship, since they are built with the knowledge from the IRs and are a basic tool for ensuring the development of entrepreneurial orientation, exploring and exploiting new products, processes and services.

The dynamic capabilities approach has generated great interest in the literature relating to business management in recent years. This approach transforms the static perspective of the resource-based view in an approach that includes the attainment of a competitive advantage in a dynamic context (Helfat and Martin, 2015). Thus, in highly dynamic environments, a sustainable competitive advantage involves not only the complexity to replicate the firm's valuable resources, but also the difficulty in replicating their dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007).

One of the main criticisms received in the early founding stage of this approach is the difficulty to empirically measure the concept (Easterby-Smith et al., 2009). A set of processes and routines has been identified, and these components form the dimensions of dynamic capabilities (Teece, 2007). We identify three main dimensions of dynamic capabilities (Wang and Ahmed, 2007): adaptive capacity – firms’ ability to identify and capitalize the emerging market opportunities –; absorptive capacity – firms’ ability to recognize the value of new outside information, assimilate it and use it for a commercial purpose –; and innovation capacity – firms’ ability to develop new products and markets –. Although they are conceptually different, they are highly correlated.

Previously, we have provided arguments about the role of the closure of IRs as a driver to the firm's entrepreneurial orientation development. However, the density and strength of IRs, because of inherent disadvantages, is not a sufficient condition to lead firms to a greater entrepreneurial orientation. Only if companies orient their closed IRs to obtain dynamic capabilities, may they overcome the disadvantages of the closed IRs to exhibit a higher entrepreneurial orientation. Then, dynamic capabilities are a key explanatory factor linking closure of IRs with the firm's entrepreneurial orientation.

On one side, several studies have attempted to analyze what the origin of firms’ capabilities is (Ethiraj et al., 2005), highlighting the key role played by IRs to generate strategic resources and capabilities (Huang, 2011). Zahra and George (2002) suggest that IRs generate several mechanisms of social integration and they can transform external knowledge on firms’ distinctive capabilities. Thus, the most relevant resources and capabilities are socially constructed (Schoemaker and Jonker, 2005). Closed IRs provide access to knowledge and resources that are not readily available through market exchanges (Gulati et al., 2000). One of the key benefits of having dense and strong IRs is the access to specific tacit knowledge and external information that is difficult to obtain by other ways and favours the development of capabilities (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). In this manner, closed IRs of firms provide access to new information that improves the possibilities of the firm to explore, identify and perceive changes in the environment and develop their ability of adapting to them (Zhang and Wu, 2013). Also, the closure of IRs, facilitating the transfer of tacit and complex knowledge, enhances the ability of firms to recognize and evaluate external information (Zhang and Wu, 2013). Therefore, the absorptive capacity is determined by absorption of new external knowledge through IRs and its exploitation in the routines and processes of the firm (Todorova and Durisin, 2007). Finally, closed IRs of firms strengthen the innovation capacity because the processes involved are usually associated with insufficient resources, especially tacit knowledge. The possibility of getting this type of knowledge from external actors through IRs is one of the essential factors for the development of firms’ innovation abilities (Frishammar et al., 2012). In short, closed IRs not only allow firms to acquire knowledge more quickly, but also provide certainty about how to use this knowledge to develop new dynamic capabilities.

On the other hand, the resource-based view indicates that a firm's resources and capabilities have a significant influence on its strategic orientation (Teece et al., 1997). From this approach, several studies have pointed out that the chances of a firm carrying out an entrepreneurial orientation depend on its capabilities. Currently, very few studies have provided a convincing explanation as to the ability of some firms to create, discover and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities continuously. Zahra et al. (2006) propose that one of the sources of entrepreneurial orientation differences between firms lies in the development and implementation of firms’ dynamic capabilities. This positive effect of the dynamic capabilities is highlighted in the different dimensions of the entrepreneurial orientation. Thus, the capability to obtain, assimilate and exploit new knowledge encourages the company to develop greater innovativeness (Kyrgidou and Spyropoulou, 2013). Dynamic capabilities also contribute to the recognition and ability to take advantage of the opportunities to develop and introduce new products in the market (Helfat and Martin, 2015). Furthermore, the information provided by them allows better interpretation of the changes and their potential consequences, which makes the company more likely to take risky actions (Liao et al., 2003). Dynamic capabilities also facilitate the early perception of opportunities and threats that drive more aggressive behaviour from the company trying to anticipate the competitive action of rivals (Barringer and Bluedorn, 1999). Finally, the mechanisms of knowledge and learning absorption offered to employees of the company allow them the possibility of introducing creative ideas freely, encouraging the autonomy of workers and equipment to develop new products (Caloghirou et al., 2004).

We propose that dynamic capabilities have a mediating role between closure of IRs and entrepreneurial orientation. Therefore, dynamic capabilities are essential to transform the benefits of having density and strength IRs in a higher entrepreneurial orientation. The existence of knowledge flows between firms through higher closure of IRs, does not guarantee the transformation of this knowledge into a higher entrepreneurial orientation. This will only be the case if the firm takes advantage of the knowledge from their closed IRs to generate capabilities, enabling it to identify, assimilate, transform and exploit this knowledge (Zhang and Wu, 2013). Therefore, dense networks and strong ties allow firms to get access to a high quality tacit knowledge, which is the base for the development of capabilities needed to explore and exploit the environment opportunities (Rowley et al., 2000). Thus, dynamic capabilities drive firms to effectively exploit the knowledge gained from their dense and strong IRs to generate a greater entrepreneurial orientation (Engelen et al., 2014).

In sum, dynamic capabilities lead to and explain the effect of closure of IRs on a firms’ entrepreneurial orientation and dimensions. In this way, firms that are able to develop strong dynamic capabilities from their closed IRs are in a better position to take advantage of an entrepreneurial behaviour and, thus, they will tend towards entrepreneurial orientation. From the previous arguments, we propose the next hypotheses:

H1. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation.

H1a. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ innovativeness.

H1b. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ proactiveness.

H1c. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ risk-taking.

H1d. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ competitive aggressiveness.

H1e. Dynamic capabilities mediate the relationship between closure of IRs and firms’ autonomy.

The empirical study was conducted in the Spanish agri-food industry. This industry is one of the main economic engines in the country. It combines the maturity, the tradition, the predominance of small firms, territorial embeddedness and proximity to raw materials, with an increasing internationalization, technological innovation and the development of distribution channels in order to compete globally. These factors provide the need of these firms to relate with other firms to acquire the necessary knowledge to perform these actions. Therefore, we consider it an appropriate sector to analyze the role of IRs to develop both an entrepreneurial behaviour and internal capabilities necessary to acquire and exploit both possessed and potential knowledge. In addition, it is particularly appropriate for our research to analyze a mature and traditional industry. First, IRs require a wide period of time to develop. Second, the highly competitive environment of these mature industries allows us to study several aspects related to the accumulation, assimilation and exploitation of knowledge.

To obtain the information for the development of our research, we explored several databases – SABI,3 Camerdata,4 INE5 and those of food-industry associations –. In order to configure our database, we put forward an additional requirement, namely not to include firms with less than 20 employees. We obtained a total of 3992 firms. Once duplicated cases, errors and firms that had ceased their activity were eliminated, a total of 2887 firms remained. Before launching the questionnaire in order to ensure as far as possible the quality of responses, we organized and designed the questionnaire according to the proposals suggested by Dillman (1978). A postal questionnaire was then sent to the firms’ CEOs in order to ensure that they had the required expertise to answer the questionnaire.6 Within two weeks of the mail questionnaire being sent, we repeated the mailing by e-mail once a month during the data collection. In the end, we obtained a total of 292 valid questionnaires, which represents a response rate of 10.11% for a confidence level of 95% and the most unfavourable situation of p=q=0.5. The sample represents a sampling error of 5.44%. This can be considered an acceptable response rate in comparison to similar studies using postal/on-line questionnaires (Engelen, 2010).

In order to check whether the sample data were representative of the population under scrutiny, we conducted a mean difference test. We did not find significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of age and size. In addition, we did not observe significant differences in the structural characteristics between early and late respondents for the dependent, independent, intermediate or control variables (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). Finally, we carried out two tests to check common methodological bias. First, we performed a Harman's test7 (Podsakoff et al., 2003) and then another, through the evaluation of a random subsample8 of our total sample of firms. We sent back a questionnaire to firms that had responded previously for completion by another manager. We did not find any significant differences between the first and second manager in the variables used in our study, and between firms that responded to this new survey and those firms that did not for independent, dependent and control variables.

Variables9Closure of IRs: To measure this variable we use a reflective second-order construct consisting of two components. Firstly, we used the scale proposed by Maula et al. (2003) which measures the frequency and strength of the IRs. Secondly, we used a scale of density of IRs adapted from Molina and Ares (2007) which has been used in recent studies (Parra-Requena et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurial orientation: As noted above, we analyzed this variable across the five dimensions proposed by Lumpkin and Dess (1996) – innovativeness, proactiveness, risk-taking, competitive aggressiveness and autonomy-. In order to measure the first three dimensions of the construct, we incorporated the scale of nine items proposed by Covin and Slevin (1989), widely used in the previous literature. Regarding the two additional dimensions, we used the subsequent scale proposed by Lumpkin and Dess (2001) to measure competitive aggressiveness. Finally, to measure autonomy we selected the scale proposed by Lumpkin et al. (2009). We consider entrepreneurial orientation as a reflective second-order construct consisting of the five dimensions, in line with studies such as those of Lee and Sukoco (2007) and Li et al. (2009).

Dynamic capabilities: We use the classification proposed by Wang and Ahmed (2007). This is close to Teece's (2007) classification and distinguishes three types of capabilities: adaptive capacity, absorptive capacity and innovative capacity. As performed by Monferrer et al. (2015) in their study, we adapted the scale proposed by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) to measure adaptive capacity and the scale proposed by Akman and Yilmaz (2008) to measure innovative capacity. For measuring absorptive capacity, we selected the scale proposed by Flatten et al. (2011). These three capabilities form a reflective second-order construct.

Control variables: We introduced several control variables. Firm size is measured by the number of employees. The literature shows conflicting results, although generally, larger firms have the resources needed to develop an entrepreneurial behaviour (Su et al., 2009). The firm age is measured as the difference between the firm's year of establishment and the year of data collection. According to Simsek et al. (2010) we consider that older firms tend to have a lower entrepreneurial orientation, so we expect a negative influence of firm's age on entrepreneurial orientation. Moreover, we adapted the scale proposed by Jaworski and Kohli (1993) to measure technological dynamism. This variable reflects the difficulty in predicting changes within the industry, thereby influencing the strategic behaviour of the firm. In a similar vein to technological dynamism, the literature has noted that market dynamism has a positive effect on a firm's entrepreneurial orientation because firms can exploit the opportunities that may arise in the environment and increase the uncertainty of competitors (Atuahene-Gima et al., 2006). We decided to use the three items scale proposed by Atuahene-Gima et al. (2006) to measure this variable. We expect a positive influence of both variables, because the firm's entrepreneurial behaviour in dynamic environments is more relevant (Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Finally, we also incorporate a sub-industry variable to control the potential heterogeneity of firms that belong to different agro-food industry sub-sectors – foods (0) or beverages (1) –. We include this dummy variable due to the singular competitive conditions of each of the branches of the industry, which can affect the processes and behaviours of firms (Bremmers et al., 2007).

AnalysisWe have used structural equations analysis because of the advantages it offers over traditional multivariate analysis (Haenlein and Kaplan, 2004). Particularly, in order to evaluate our model and analyze data we use Partial Least Squares (PLS) with SmartPLS software. PLS was used because it is ideal for predictive purposes, where theoretical knowledge is underdeveloped. In this case, we do not have a consolidated model and theory to confirm, so PLS is the best option (Barclay et al., 1995). Furthermore, PLS avoids two serious problems in the form of improper solutions and indeterminacy of factors (Fornell and Bookstein, 1982). In keeping with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2014) we use PLS because the goal is predicting key target constructs or identifying key ‘driver’ constructs; the research is exploratory or an extension of an existing structural theory and the objective of the research is to use latent variable scores in subsequent analyses. Finally, SEM techniques are recommended to test the mediation hypothesis. Thus, several recent studies have analyzed mediating effects with the PLS technique (Parra-Requena et al., 2015, among others).

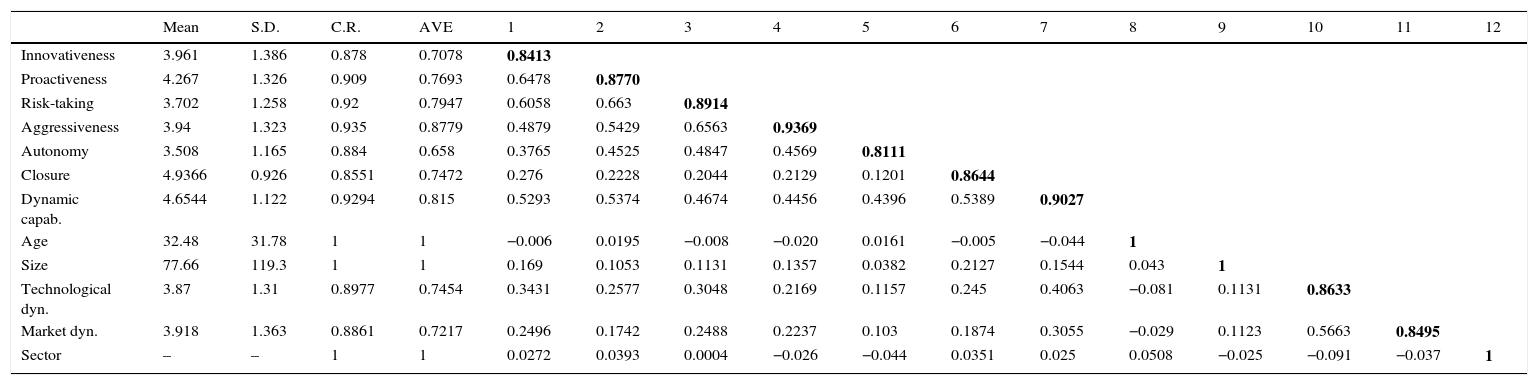

ResultsEvaluation of the measurement modelWe developed four analyses for evaluating the measurement model using PLS: individual item reliability, scale reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity. First, individual item reliability is assessed by analysing item loading (λ). All indicators exceed the value (0.707) proposed by Carmines and Zeller (1979). Regarding the scale reliability, we analyzed the composite reliability (ρc). As can be observed in Table 1, all the scores obtained have a value greater than 0.8 (Nunnally, 1978) except hostility (0.745), so they show a strict reliability. In order to evaluate convergent validity, we analyze the average variance extracted (AVE). All constructs have an AVE above the recommended threshold of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) (Table 1).

Scale reliability and validity.

| Mean | S.D. | C.R. | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovativeness | 3.961 | 1.386 | 0.878 | 0.7078 | 0.8413 | |||||||||||

| Proactiveness | 4.267 | 1.326 | 0.909 | 0.7693 | 0.6478 | 0.8770 | ||||||||||

| Risk-taking | 3.702 | 1.258 | 0.92 | 0.7947 | 0.6058 | 0.663 | 0.8914 | |||||||||

| Aggressiveness | 3.94 | 1.323 | 0.935 | 0.8779 | 0.4879 | 0.5429 | 0.6563 | 0.9369 | ||||||||

| Autonomy | 3.508 | 1.165 | 0.884 | 0.658 | 0.3765 | 0.4525 | 0.4847 | 0.4569 | 0.8111 | |||||||

| Closure | 4.9366 | 0.926 | 0.8551 | 0.7472 | 0.276 | 0.2228 | 0.2044 | 0.2129 | 0.1201 | 0.8644 | ||||||

| Dynamic capab. | 4.6544 | 1.122 | 0.9294 | 0.815 | 0.5293 | 0.5374 | 0.4674 | 0.4456 | 0.4396 | 0.5389 | 0.9027 | |||||

| Age | 32.48 | 31.78 | 1 | 1 | −0.006 | 0.0195 | −0.008 | −0.020 | 0.0161 | −0.005 | −0.044 | 1 | ||||

| Size | 77.66 | 119.3 | 1 | 1 | 0.169 | 0.1053 | 0.1131 | 0.1357 | 0.0382 | 0.2127 | 0.1544 | 0.043 | 1 | |||

| Technological dyn. | 3.87 | 1.31 | 0.8977 | 0.7454 | 0.3431 | 0.2577 | 0.3048 | 0.2169 | 0.1157 | 0.245 | 0.4063 | −0.081 | 0.1131 | 0.8633 | ||

| Market dyn. | 3.918 | 1.363 | 0.8861 | 0.7217 | 0.2496 | 0.1742 | 0.2488 | 0.2237 | 0.103 | 0.1874 | 0.3055 | −0.029 | 0.1123 | 0.5663 | 0.8495 | |

| Sector | – | – | 1 | 1 | 0.0272 | 0.0393 | 0.0004 | −0.026 | −0.044 | 0.0351 | 0.025 | 0.0508 | −0.025 | −0.091 | −0.037 | 1 |

Bold numbers represent the square root of the AVE of each construct.

For discriminant validity, Barclay et al. (1995) note that the shared variance between a variable and its indicators must be higher than the variance shared with other variables in the model, as we observe in our results – Table 1.

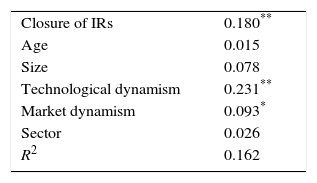

Evaluation of the structural modelThe results show that closure of IRs has a positive and significant initial effect on entrepreneurial orientation (Table 2).

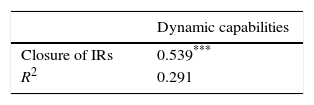

Table 3 presents the effect of closure of IRs on dynamic capabilities, showing a positive and significant effect (β=0.539; p<0.001). In addition, dynamic capabilities exert a positive and significant influence on a firm's entrepreneurial orientation (β=0.621; p<0.001).

When we introduce the dynamic capabilities as an intermediate variable, the direct relationship of closure of IRs on the firm's entrepreneurial orientation decreases significantly (β=−0.107; p<0.05), confirming our proposed general hypothesis.

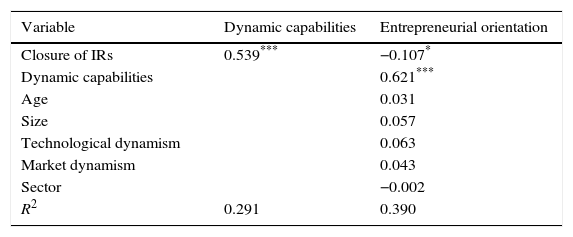

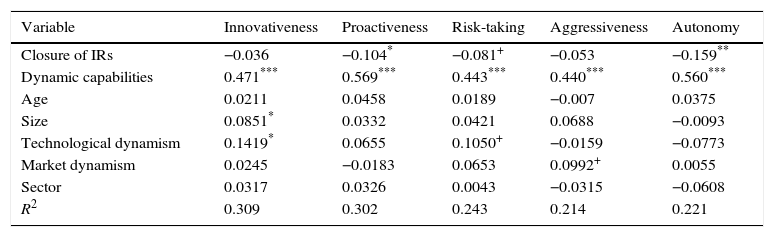

Moreover, we analyzed the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities in the relationship of closure of IRs on each entrepreneurial orientation dimension. In this sense, closure of IRs has an initial positive and significant effect on the five entrepreneurial orientation dimensions (Table 4) and on dynamic capabilities (Table 5). In Table 6, we observe that dynamic capabilities has a positive and significant effect on entrepreneurial orientation dimensions. Finally, when we introduce dynamic capabilities as a mediator variable, the direct relationship of closure of IRs on each entrepreneurial orientation dimension is eliminated, allowing us to confirm our sub-hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d and 1e.10 The relationship of closure of IRs in each entrepreneurial orientation dimension is negative and significant in the case of proactiveness (β=−0.104, p<0.05), autonomy (β=−0.159, p<0.05) and risk-taking (β=−0.081, p<0.1), showing a suppression effect, like the results obtained with the entrepreneurial orientation aggregated construct. A suppression effect, within a mediation model, is present when the direct and mediated effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable have opposite signs (MacKinnon et al., 2000). Then, a suppressor variable is “a variable which increases the predictive validity of another variable (or set of variables) by its inclusion in a regression equation” (Conger, 1974: 36–37). The omission of a suppressor will lead to a wrong estimation of the real effect of a dependent variable on an independent variable, reducing, inflating or changing the sign of the relationship between them.

Direct effect of closure of IRs on each entrepreneurial orientation.

| Variable | Innovativeness | Proactiveness | Risk-taking | Aggressiveness | Autonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closure of IRs | 0.179** | 0.155** | 0.123* | 0.146* | 0.097* |

| Age | 0.010 | 0.033 | 0.007 | −0.011 | 0.025 |

| Size | 0.096* | 0.046 | 0.052 | 0.081* | 0.003 |

| Technological dynamism | 0.261*** | 0.207** | 0.216** | 0.095 | 0.061 |

| Market dynamism | 0.060 | 0.025 | 0.099 | 0.132+ | 0.055 |

| Sector | 0.048 | 0.054 | 0.025 | −0.016 | −0.038 |

| R2 | 0.172 | 0.100 | 0.122 | 0.093 | 0.027 |

Direct effect of closure of IRs on dynamic capabilities.

| Dynamic capabilities | |

|---|---|

| Closure of IRs | 0.539*** |

| R2 | 0.291 |

Results of the global model.

| Variable | Innovativeness | Proactiveness | Risk-taking | Aggressiveness | Autonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closure of IRs | −0.036 | −0.104* | −0.081+ | −0.053 | −0.159** |

| Dynamic capabilities | 0.471*** | 0.569*** | 0.443*** | 0.440*** | 0.560*** |

| Age | 0.0211 | 0.0458 | 0.0189 | −0.007 | 0.0375 |

| Size | 0.0851* | 0.0332 | 0.0421 | 0.0688 | −0.0093 |

| Technological dynamism | 0.1419* | 0.0655 | 0.1050+ | −0.0159 | −0.0773 |

| Market dynamism | 0.0245 | −0.0183 | 0.0653 | 0.0992+ | 0.0055 |

| Sector | 0.0317 | 0.0326 | 0.0043 | −0.0315 | −0.0608 |

| R2 | 0.309 | 0.302 | 0.243 | 0.214 | 0.221 |

In Tables 3 and 5 we can observe the results of the global model. These models show a significant change of R2 from the initial direct model. In addition, to analyze the overall fit, we obtained the Goodness of Fit index (GoF). In our case, both the direct model – 0.312 and indirect model – 0.483 – have a good fit and exceed the value recommended in the literature – 0.31 – (Tenenhaus et al., 2005). Moreover, we use the Q2 index developed by Stone and Geisser to measure the predictive relevance of our model. The literature suggests that values of Q2 above 0 imply that the model has predictive relevance. In our global model, we observe a correct predictive relevance – 0.2371.

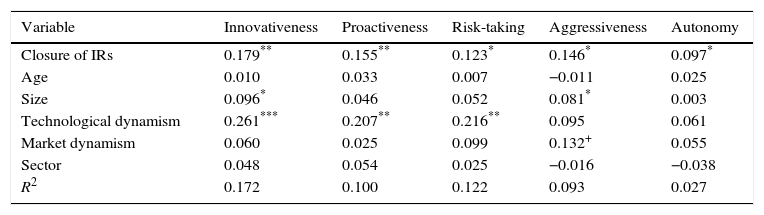

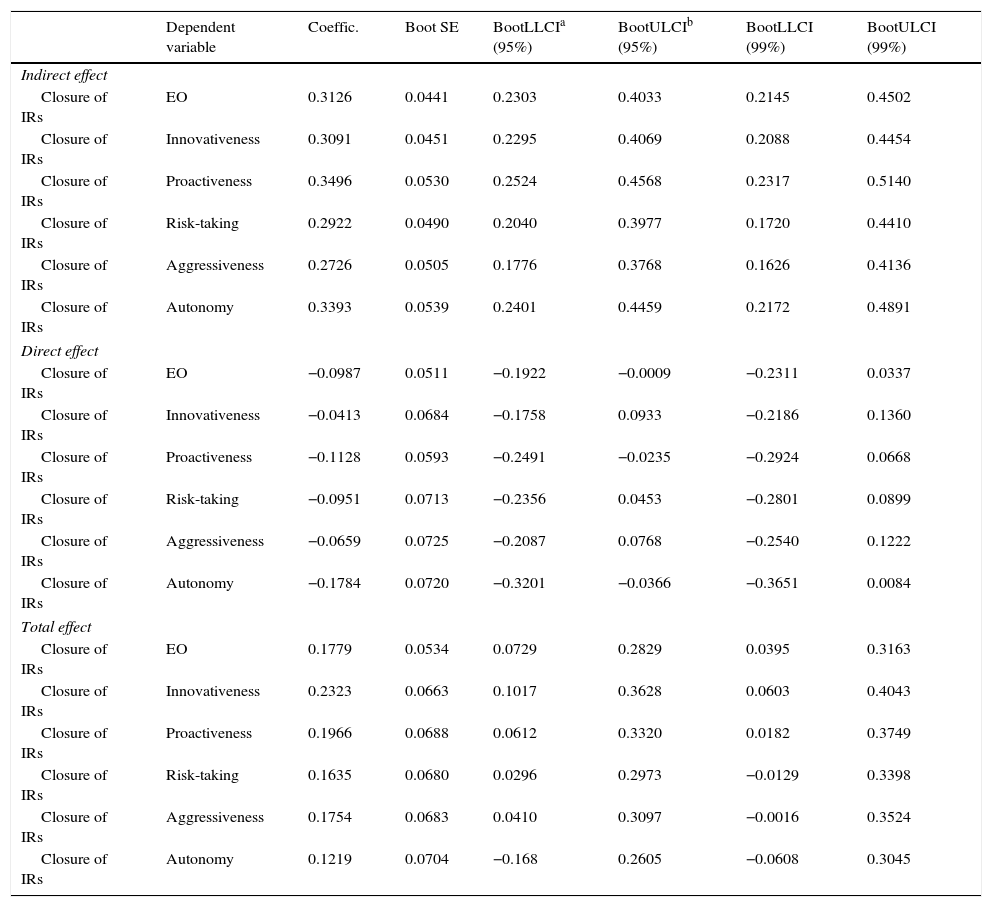

The results could lead to confirmation of an erroneous mediating effect if the significance of the regression coefficients is analyzed in isolation. In this instance the absolute effect must be examined. Hayes (2009) points out that bootstrap resampling is the best option to check the indirect effect. This method is a nonparametric approach which has greater power and control over type I errors. Following the lead of Preacher and Hayes (2008), we studied the significance of direct and indirect effects using PROCESS macro for SPSS. The results – Table 7 – confirm the validity of the positive indirect effects through dynamic capabilities and the negative direct effect of closure of IRs on a firm's entrepreneurial orientation, for a confidence level of 95%, supporting the main findings obtained in the regression model. In addition, the significance of effects for each firm's entrepreneurial orientation dimensions also support the suppression effect for proactiveness, risk-taking and autonomy. Outcomes corroborate that closure of IRs exerts a positive indirect effect through dynamic capabilities and a negative direct effect on them.

Test of mediation effect of dynamic capabilities. Bootstrap results.

| Dependent variable | Coeffic. | Boot SE | BootLLCIa (95%) | BootULCIb (95%) | BootLLCI (99%) | BootULCI (99%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| Closure of IRs | EO | 0.3126 | 0.0441 | 0.2303 | 0.4033 | 0.2145 | 0.4502 |

| Closure of IRs | Innovativeness | 0.3091 | 0.0451 | 0.2295 | 0.4069 | 0.2088 | 0.4454 |

| Closure of IRs | Proactiveness | 0.3496 | 0.0530 | 0.2524 | 0.4568 | 0.2317 | 0.5140 |

| Closure of IRs | Risk-taking | 0.2922 | 0.0490 | 0.2040 | 0.3977 | 0.1720 | 0.4410 |

| Closure of IRs | Aggressiveness | 0.2726 | 0.0505 | 0.1776 | 0.3768 | 0.1626 | 0.4136 |

| Closure of IRs | Autonomy | 0.3393 | 0.0539 | 0.2401 | 0.4459 | 0.2172 | 0.4891 |

| Direct effect | |||||||

| Closure of IRs | EO | −0.0987 | 0.0511 | −0.1922 | −0.0009 | −0.2311 | 0.0337 |

| Closure of IRs | Innovativeness | −0.0413 | 0.0684 | −0.1758 | 0.0933 | −0.2186 | 0.1360 |

| Closure of IRs | Proactiveness | −0.1128 | 0.0593 | −0.2491 | −0.0235 | −0.2924 | 0.0668 |

| Closure of IRs | Risk-taking | −0.0951 | 0.0713 | −0.2356 | 0.0453 | −0.2801 | 0.0899 |

| Closure of IRs | Aggressiveness | −0.0659 | 0.0725 | −0.2087 | 0.0768 | −0.2540 | 0.1222 |

| Closure of IRs | Autonomy | −0.1784 | 0.0720 | −0.3201 | −0.0366 | −0.3651 | 0.0084 |

| Total effect | |||||||

| Closure of IRs | EO | 0.1779 | 0.0534 | 0.0729 | 0.2829 | 0.0395 | 0.3163 |

| Closure of IRs | Innovativeness | 0.2323 | 0.0663 | 0.1017 | 0.3628 | 0.0603 | 0.4043 |

| Closure of IRs | Proactiveness | 0.1966 | 0.0688 | 0.0612 | 0.3320 | 0.0182 | 0.3749 |

| Closure of IRs | Risk-taking | 0.1635 | 0.0680 | 0.0296 | 0.2973 | −0.0129 | 0.3398 |

| Closure of IRs | Aggressiveness | 0.1754 | 0.0683 | 0.0410 | 0.3097 | −0.0016 | 0.3524 |

| Closure of IRs | Autonomy | 0.1219 | 0.0704 | −0.168 | 0.2605 | −0.0608 | 0.3045 |

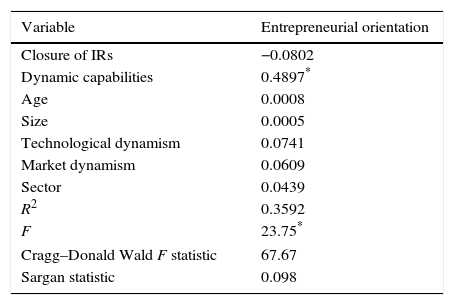

Despite the acceptance of the use of Baron and Kenny methodology to check mediating effects, this method can generate biased and inconsistent estimators because there may be correlations between the error terms of the mediation model equations (Shaver, 2005). With this in mind, possible endogeneity in our model was controlled by using the process employed by Bojica et al. (2012). To this end, we used the two-stage least-squares technique to test our mediation hypothesis (Bascle, 2008). Applying the Shaver (2005) indications we introduced two distinct instruments: knowledge acquisition and availability of financial resources. These concepts were also measured in the questionnaire. Previous literature suggests that knowledge acquisition and financial resources are causally related with dynamic capabilities (Helfat and Martin, 2015). These variables satisfy the conditions proposed by Shaver (2005): First, they directly affect the mediating variable but do not directly affect the dependent variable. Secondly, they explain a significant percentage of the variance of the mediating variable. In addition, the results of Sargan statistic and the first stage F-statistic – Wald F statistic (Table 8), indicate the adequacy of the instrumental variables used and that their exogeneity is respected (Bascle, 2008).

Results of the two-stages least-squares analysis.

The results of the two-stage least-square analysis confirm a mediating effect of dynamic capabilities on the relationship between closure of IRs and entrepreneurial orientation, conditional to the instruments used (Table 8). The analysis with instrumental variables presents similar results to those obtained in the mediation analysis. This suggests that endogeneity and reverse-causality have not exerted any influence on our mediated relationship. Therefore, we can indicate that the causality between our variables follows the relationship proposed and not the opposite direction.

Discussion and conclusionsIn this paper, we contribute towards explaining the influence of IRs as a determinant factor of firms’ entrepreneurial orientation, probing into its generation and development (Covin and Lumpkin, 2011) and providing a better understanding of the real effect of closure of IRs. We contribute to the detection of which factors explain when and how a positive or negative effect of closure of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation is generated. Therefore, we analyze how dynamic capabilities affect this relationship, exposing the latent negative direct effect of closure of IRs, in accordance with several previous studies. We highlight the key role of dynamic capabilities to connect closure of IRs with firms’ entrepreneurial orientation. When we incorporate the mediating variable, the positive and significant effect of closure of IRs on firms’ entrepreneurial orientation becomes negative and significant. This suppression effect reveals that if we extract the positive indirect effect of closure of IRs on entrepreneurial orientation through dynamic capabilities, a real negative and significant direct effect would emerge. Thus, closure of IRs that is not focused on generating and developing capabilities, often generates a lock-in, inertia, information redundancy and myopia, discouraging the development of entrepreneurial orientation.

Exploring the effect of dynamic capabilities in the effect of closure of IRs on firms’ entrepreneurial orientation dimensions further, we observe a suppression effect of dynamic capabilities on the relationship of IR closure with proactiveness, risk-taking and autonomy. This confirms that the redundant knowledge of IR closure restricts the detection of new opportunities in the environment and the anticipation of future demands of customers and risky behaviour because the knowledge of the firm is not renewed. Also, results confirm that closure of IRs limit the firm's autonomy. Firms’ in closed IRs tend to have similar behaviour, isolating those firms that behave differently. Against the results in these variables, closure of IRs does not reduce the willingness of the firm to engage in creativity and experimentation or the propensity to pursue new business models or products, as it does not represent a specific innovation, but a way of going about decision making actions. Therefore, closure of IRs cannot limit the attitude of the firm or its internal culture. The same argument can be established for the competitive aggressiveness dimension. Thus, closure of IRs does not reduce the firm's propensity to challenge its competitors directly or the willingness of the firm to enter or improve their position in the industry because it is a reflection of the firm's internal culture or attitude. Therefore, high density and strength of the IRs will not discourage firms’ entrepreneurial orientation if they strengthen the leading role of dynamic capabilities.

We consider that one of the main contributions of the study is that it unmasks the dark side of dense and strong IRs on firms’ entrepreneurial orientation, that emerges when IRs are not driven through the generation and development of dynamic capabilities. Our study provides new arguments and evidence in the debate about the controversy of the effects of closure of IRs, mainly cooperative relationships. These effects are diluted in works that study social capital as an unidimensional construct. Thus, we identify and contrast the perverse effects suggested in the literature which can be derived from excessively closed IRs. However, we found in the development of dynamic capabilities a common bridge to drive network density and social interaction to firm's entrepreneurial orientation. We emphasize the role of these socially constructed capabilities because they are an essential driver mechanism to counteract the negative effect of IRs on firm's entrepreneurial orientation. Furthermore, we contribute to reinforcing the dual approach to entrepreneurial orientation of De Clercq et al. (2013), combining both the unidimensional and multidimensional focus of entrepreneurial orientation. Additionally, this paper discusses in depth the relational determinants of entrepreneurial orientation, as it has been broadly described (Covin and Lumpkin, 2011). Finally, we link three theoretical approaches scarcely analyzed together in the literature to date, delving into the consequences of IRs – social capital, entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities. The relevance of social capital theory in understanding the implications of IR networks at firm level is particularly highlighted.

The results we have obtained allow us to suggest the existence of several implications for both managers and institutions. Firstly, the development of dense and strong IRs is essential for the development of any entrepreneurial behaviour. These IRs will facilitate the sharing of resources, particularly knowledge, which will allow firms to modify their internal capabilities to better face environmental changes. However, firms should try to drive their closed IRs to develop and enhance the firm's dynamic capabilities in order to maintain and develop an entrepreneurial orientation. Managers should also monitor their propensity to maintain an imitating, reactive and risk-averse behaviour derived from closed IRs. We also consider that firms not only focus their efforts to improve the density of their networks and develop ties characterized by greater strength and frequency of interaction. These efforts need more resources than the benefit they may derive from them. Finally, we recommend that those institutions related to the agri-food industry should focus on facilitating the generation of IRs, which will improve the amount of knowledge possessed or the potential knowledge that they can access. Furthermore, institutions should focus on developing new opportunities for firms that do not have independent access, mainly those actions related to external trade.

Despite the precautions taken in the realization of this paper, several limitations are apparent. First, we consider dynamic capabilities as higher-order constructs. However, we note that there is a high correlation between the dynamic capability dimensions. Secondly, we assume the limitations arising from the absence of longitudinal information in order to contrast our hypothesis. Furthermore, dynamic capability is still a very open issue in which multiple classifications of its dimensions are considered. However, we chose the classification proposed by Wang and Ahmed (2007) by reason of the broad development of their measurement scales and their adaptation to the context of our work. Thirdly, despite previous efforts to validate the scales and measures used in our model, we cannot exclude a potential bias in the use of these measures. With this in mind, previous efforts to select reliability and validity scales, as far as possible, go some way towards ensuring their validity. Also, managers’ perceptions may not necessarily coincide with the objective values, which can cause a possible bias in the results. However, we believe that managers’ perceptions, in accordance with previous studies in this field of research, determine the firm's strategic behaviour and reflect significantly the firm's reality, even more precisely than some objective values. Furthermore, the control of the bias developed with a sub-sample provides greater validity to the managers’ perceptions with regard to our variables. Finally, we must assume several limitations of PLS, for example the use of PLS-SEM does not offer goodness of measurement, relationships are always unidirectional, and with a small sample size, PLS can offer high coefficient values, although in our case this limitation does not affect our study.

As future lines of research, we suggest further investigating the effects of specific IRs – such as strategic alliances or franchising – on entrepreneurial orientation. We also propose to address how closure of IRs and dynamic capabilities affect, independently and jointly, the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. Furthermore, we propose that the independent role that each dynamic capability dimension can have on a firm's entrepreneurial orientation be analyzed. Although we have noted that these dimensions are highly correlated, it would be advisable to analyze the unique effect of each dimension on the firm's entrepreneurial orientation. Finally, one interesting line of research would be to study the possible long-term interdependence between closure of IRs and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation through a longitudinal study.

This research was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain – ERDF [Projects: ECO2013-42387-P and ECO2016-75781-P]. We wish to thank the Guest Editors and the three anonymous reviewers of BRQ the proposed comments and suggestions.

IRs. Interorganizational relationships.

The SIRO group is a company dedicated to the transformation of cereals into different foodstuffs.

SABI compiles a directory of Spanish and Portuguese firms with general information and financial data.

Camerdata database is a directory of all Spanish firms from the local Chambers of Commerce.

INE: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.

Those surveys received that had not been answered by the firm's manager were eliminated from the sample.

The principal component factor analysis of the all variables used in our model showed 8 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 (68.59% of the variance in the data). Then, common method bias does not seem to be a problem: we identify more than one factor, the first factor accounted for 30.93% of the variance and the unrotated factor structure does not show a general factor (Gruber et al., 2010).

Sub-sample of 49 firms (16.78% of the total sample) of which we obtain a second response from a second manager of the same questionnaire previously sent to our population.

All items were measured on 7-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), except the entrepreneurial orientation scale in which we used pairs of opposing statements.

This mediating relationship of dynamic capabilities was analyzed in other dependent variables: new product performance and new process performance. The results of this analysis confirm that dynamic capabilities acts as a mediating variable on the relationship between structural embeddedness and these dependent variables. These models explain 36% and 40% of the variance of dependent variables: new product performance and new process performance, respectively. Results are available upon request.