The aim of this study is to explore the human or employee-related factors that shape customer satisfaction in the context of call centres. The literature review draws from a range of disperse disciplines including Service Quality, Human Resource Management and Marketing. The empirical study explores the different variables identified to obtain a nuanced analysis of the employee-related paths that lead to customer satisfaction in call centres. The study employs data from 109 call centres and utilises PLS for our exploratory purposes. Call centre managers should note that investing in HR practices will pay off in terms of improving the elusive phenomenon of customer satisfaction within call centres.

The call centre industry is a peculiar service industry, in as much as it is almost entirely based on a voice-to-voice encounter between the employee and the customer, on opposite ends of the telephone line. In general, customers are less satisfied with the service they receive from call centres than from the more traditional brick n’ mortar, or face to face service encounters (Bennington et al., 2000; Makarem, 2009). Academic researchers attribute this dislike of call centres to various reasons, such as cultural acceptance of technology (Bennington et al., 2000), a general lack of experience in dealing with technology (Mittal et al., 1999) and the difficulties experienced by older consumers with technology (Makarem, 2009). In addition, people often feel irritated when dealing with automated answering machines (Prendergast and Marr, 1994), with rude employees, with long waiting times and overall poor service (Helms and Mayo, 2008). Ironically, although the concept of the call centre originated as a relationship marketing tool, it is widely accepted that customer satisfaction is not generally associated with call centre operations (Bennington et al., 2000; Makarem, 2009).

In call centres, employees (call centre operators) are the main connection between the organization and the customer. Employees are often required to undertake many different tasks at the same time (Jasmand et al., 2012). They are expected to display ambidextrous behaviour, being able to accomplish managerial requirements such as: maintaining service quality, including attentiveness, perceptiveness, responsiveness and assurance (de Ruyter and Wetzels, 2000; Upal and Dhaka, 2008), satisfy customers (Sergeant and Frenkel, 2000), solve problems (Bharadwaj and Roggeveen, 2008), attend a large number of calls in a short time while ensuring first call resolution (Cheong et al., 2008; Feinberg et al., 2000; Piercy and Rich, 2009b, 2009a) and engage in additional activities, such as adaptive selling (Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Jasmand et al., 2012). All of this often takes place in a stressful environment, dealing with problematic customers (Poddar and Madupalli, 2012; Wegge, 2006) under the managerial pressure associated with the production line approach (Gilmore and Moreland, 2000; Gilmore, 2001) and a low-cost approach to HR practices (Wallace et al., 2000; Fernie and Metcalf, 1998; Taylor et al., 2002). This extremely challenging environment and loss of control over the task activity causes exhaustion and subsequently, employee turnover or absenteeism (Poddar and Madupalli, 2012).

It is quite remarkable that, given the key role of the call centre employee in customer relations, little academic research has directly addressed the customer satisfaction metric in the context of the call centre. Accordingly, we are interested in exploring the employee-related paths that lead to customer satisfaction. In other words, we explore a variety of employee-related factors and consider how these contribute to customer satisfaction in the voice-to-voice service encounter of the call centre industry.

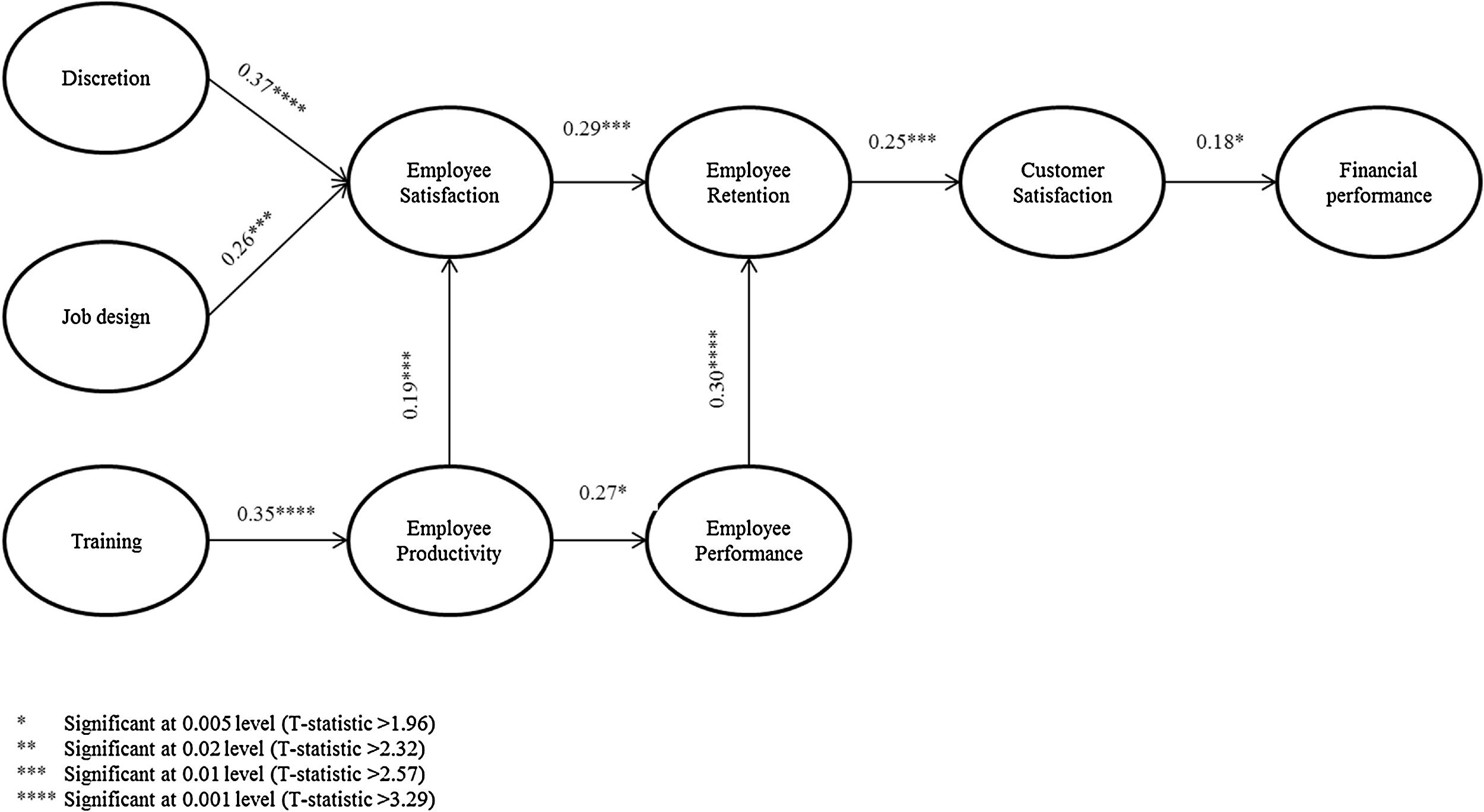

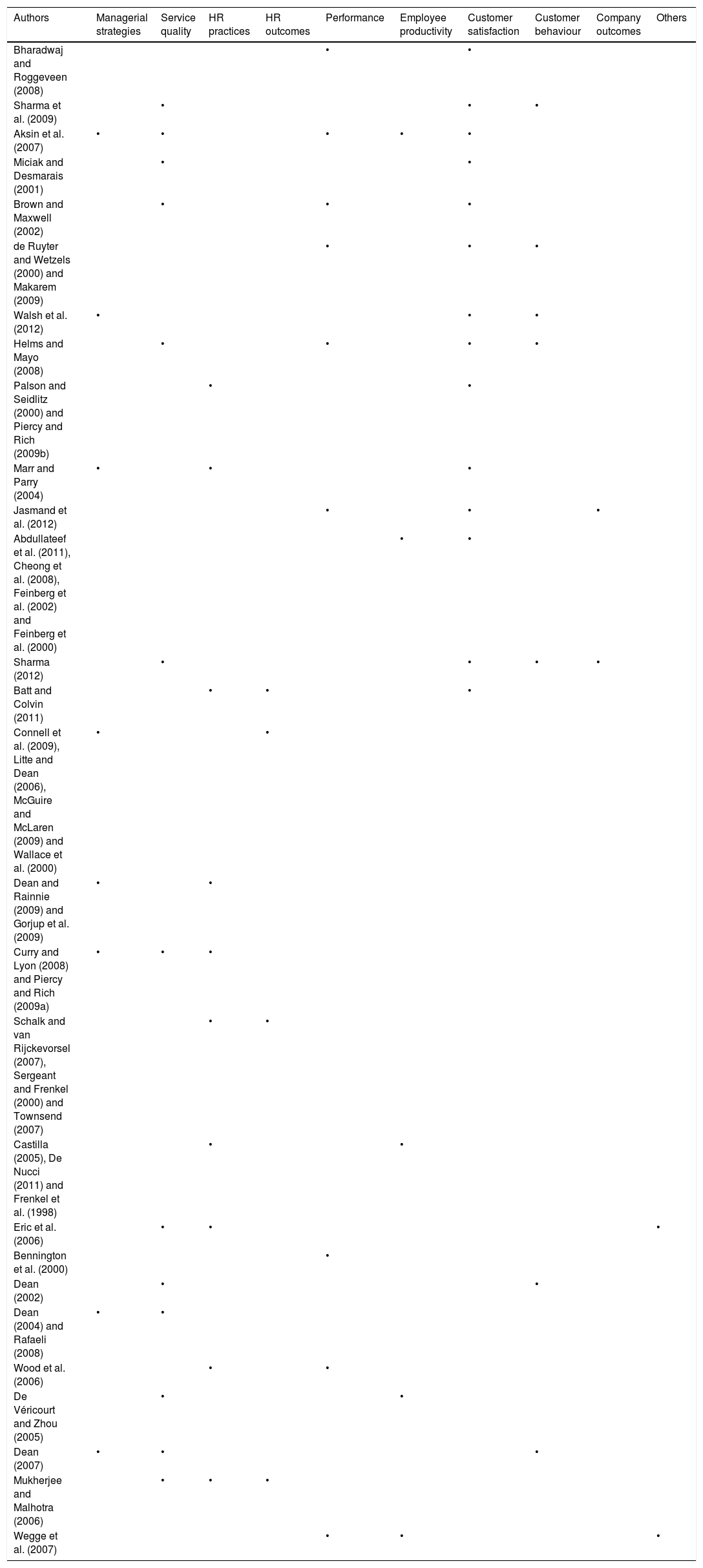

The paper is structured as follows. Firstly, in the literature review, we identify and consider the human (or employee-related) factors that influence or lead to customer satisfaction. The literature is summarised and classified in Table 1. This is followed by a section on the main takeaways from the literature review and leads directly into the formulation of the central research question, which subsequently guides the development of our research methodology. In the methodology section, we explain each of the measures used in the study. Next, we present the results and culminate with a discussion of our findings and limitations.

A categorisation of the literature on the human factor in customer satisfaction in call centres.

The preparation of the literature review was undertaken with a view to identifying the human factors that shape customer satisfaction in call centres. Firstly, we identified the relevant literature on customer satisfaction in call centres, noting that among the range of factors, some were more proximal and others more distal to the customer satisfaction concept and that there was much interaction between these factors, leading to a series of complex and intertwined relationships. Therefore, we extended the literature search in order to include related studies that despite not focusing necessarily on customer satisfaction, do consider some of the range of factors identified in the first phase of the literature search. In this way, we were able to more thoroughly explore the factors surrounding and shaping customer satisfaction in call centres, to move beyond the core factors and consider the interaction between peripheral factors. The main collection of studies identified is listed in Table 1. The literature that deals directly with customer satisfaction is grouped at the beginning of the table. The papers identified in the second part of the table are those that do not deal with customer satisfaction per sec, but deal with issues surrounding customer satisfaction. The literature is drawn from a disperse set of disciplines such as the KPI literature which is performance based, the Service Quality literature, the HRM literature and the Marketing literature. Therefore, we present the categories outlined in Table 1 as an initial contribution of this study. Beyond Table 1, the subsections of the literature review deal accordingly with each of the categories identified in the table, following the same order as they appear in the table.

Managerial strategiesAccording to the literature we can distinguish between two main managerial approaches to call centres. On the one hand, the production-line approach focuses on quantitative performance measures (such as attending a large number of calls within a short time) without considering the service quality, customer satisfaction or employee well-being (Gilmore and Moreland, 2000; Gilmore, 2001). In other words, according to this approach, the company homogenizes its operations, focuses on sales volume, and constantly monitors and controls employees, with an emphasis on recording the quantitative results.

On the other hand, the customer orientation approach focuses on delivering service quality, by attempting to commit and motivate employees through empowerment and company support (Gilmore and Moreland, 2000; Gilmore, 2001). Although some studies report the use of both quantitative and qualitative metrics to measure call centre performance (Bain et al., 2002), there is much evidence to suggest that call centre managers still focus primarily on quantitative metrics (Gilmore, 2001). Ironically, the achievement of these metrics generally have a negatively effect on employees’ ability to deliver on service quality (Dean and Rainnie, 2009). In this sense, it is essential to consider whether a call centre is set up for achieving (the commonly conflicting goals of) service quality or customer satisfaction. However, the call centre is generally seen as a functional tool, employed to achieve more customers, or as a CRM tool in order to highlight the customer orientation approach. Under the customer orientation approach, the call centre is geared towards building up stronger relationships with the customer by supporting and helping them with their requirements. Call centres generally take two basic forms, in-house or out-sourced. In-house call centres are within the same organization. Outsourced call centres offer their services to other companies who prefer to contract an outside firm to operate their call centre. Call centres may also be classified in terms of the types of telephone calls involved (inbound or outbound). In this context, managerial strategies are generally determined by the type of contract between the client company and the outsourced call centre.

The most suitable option to achieve the optimal level between employee activities and employee effort would be the partnership contract (whereby the call centre pays a user fee and also shares a part of the costs) and pay-per-call plus share costs (where the call centre earns for every call resolution and in addition shares the cost with the main company) (Ren and Zhou, 2008). Nevertheless, the issue regarding call centre managerial strategies is not about addressing causality between service quality and customer satisfaction, it is about discerning the desired outcomes for the call centres. The customer orientation approach is still considered the most suitable managerial approach for organizations that aim to ensure service quality or customer satisfaction (Curry and Lyon, 2008; Gilmore and Moreland, 2000; Gilmore, 2001).

Service qualityIn general, previous research shows a direct cause-effect relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction (Ciavolino and Dahlgaard, 2007; Maddern et al., 2007; Ravichandran et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2009; Upal and Dhaka, 2008). However, it seems that customer attitude or their previous experience with the organization moderates this relationship (Sharma et al., 2009; Sharma, 2012). In other words, regardless of the service quality level, a negative predisposition will inhibit customer satisfaction (Sharma et al., 2009). Additionally, managers, customers and employees often display different viewpoints and interpretations of service quality (Gilmore, 2001). For instance, from the customer point of view, call centre service quality depends on the ability of the call centre operator to adapt to each caller, to show empathy, attentiveness, responsiveness and authority (Bharadwaj and Roggeveen, 2008; de Ruyter and Wetzels, 2000; Burgers et al., 2000). However, managers generally disregard customer orientation and prefer operational metrics, such as speed of answers, number of calls attended, etc., in order to measure service quality (De Nucci, 2011; Jaiswal, 2008; Liu, 2010). Meanwhile, the service quality of the call centre service depends on the adaptiveness, assurance, empathy and authority of call centre agents (Burgers et al., 2000) and communication, including attentiveness, perceptiveness and responsiveness (Bharadwaj and Roggeveen, 2008; de Ruyter and Wetzels, 2000).

A number of studies consider the service quality of call centres from the alternative perspective of customer satisfaction versus dissatisfaction. According to this perspective, the factors that lead to satisfaction are not necessarily the ones that lead to dissatisfaction when they are not present. For instance, while customer satisfaction depends on employee ability to ensure first call resolution (Abdullateef et al., 2011; Aksin et al., 2007; Feinberg et al., 2000) or service level (Cheong et al., 2008), other factors such as rude employees, overall poor or slow service (Helms and Mayo, 2008) are drivers of customer dissatisfaction. Similarly, customers do not tend to mention “service speed” when they are satisfied, but they do so when the call ends in dissatisfaction (Helms and Mayo, 2008).

Although service quality and first call resolution depend mainly on employees and how they perform their tasks (Abdullateef et al., 2011; Aksin et al., 2007) there may also be a link between first call resolution and managerial strategies. In some cases, call centre jobs are designed in a way that responsibilities are distributed among agents so that employees are often required to transfer calls to other departments. Consequently, customers find themselves repeatedly facing technology barriers, while paying for the call's cost as they are waiting. Once the call is transferred to the correct agent, the customer will experiment satisfaction only if they are provided with quality information and service (Garcia et al., 2012). Therefore, employees play the key role in the actions that lead to customer satisfaction. In effect, to achieve customer satisfaction in the call centre industry, we must focus on both technology service quality and human service quality (Brown and Maxwell, 2002; Makarem, 2009; Miciak and Desmarais, 2001) and align these with customer expectations as well as with the company's forecast and managerial strategies. Therefore, achieving customer satisfaction is a complex process with many intervening factors and interrelationships.

Human resource practicesAs stated earlier, the often high pressure environment of call centres can lead to employee exhaustion, turnover and absenteeism (Poddar and Madupalli, 2012), which are the main internal problems associated with call centres (Piercy and Rich, 2009a). Indeed, it should be noted that employee behaviour and outcomes mainly depend on HR practices. For instance, some suggest that positive HR practices improve employees’ ability to deliver service quality (Litte and Dean, 2006), or that HR practices based on employee training and appraisal improve service quality as well as customer satisfaction (Curry and Lyon, 2008). However, it seems that in the call centre industry it is common to adopt sacrificial HR practices (Wallace et al., 2000) and to measure employees performance based on “hard” quantitative measures (Bain et al., 2002). Consequently, this leads to negative outcomes, such as high employee turnover or low commitment (Connell et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2000).

It is widely accepted that adopting the customer orientation approach and improving job quality solves the root cause of these negative outcomes (Batt and Colvin, 2011; Frenkel et al., 1998; Marr and Parry, 2004; Wood et al., 2006). Job quality may be shaped by external factors, such as the economic or politic situation (Holman, 2013), or by internal factors, such as training programs (Marr and Parry, 2004; Piercy and Rich, 2009a; Valverde et al., 2007), teamwork (Hutchinson et al., 2000), recruitment of emotionally ready employees (Poddar and Madupalli, 2012; Townsend, 2007) or the type of work contract (Batt and Colvin, 2011; Schalk and van Rijckevorsel, 2007; Valverde et al., 2007). For instance, hiring emotionally fit employees who are capable of dealing with stressful environments makes it possible to improve call centre results (Dean and Rainnie, 2009), and to reduce turnover and absenteeism among employees (Poddar and Madupalli, 2012; Townsend, 2007). The teamwork concept plays an important role in job design (Hutchinson et al., 2000), by incorporating dimensions such as group autonomy, decentralized problem-solving, team discretion and collective responsibility (Thompson and Wallace, 1996). However, it seems that in the context of the call centre, teams are generally conceived as tools for facilitating staff control and monitoring (Van den Broek et al., 2004). This may create a contradiction between service quality and efficiency (Raz and Blank, 2007). Additional concepts that are related to job quality and employees well-being in call centres include the physical environment and company support (McGuire and McLaren, 2009), which in turn may also contribute to achieving employee commitment (Batt and Colvin, 2011). In summary, positive HR practices in terms of recruitment, training, developing teamwork, ensuring a pleasant physical environment and company support, reduce employee's burnout, absenteeism and turnover and increase commitment among employees.

Human resource outcomesThis section considers the employee-centred outcomes of the implementation of specific human resources practises in call centres. In other words, we examine the consequences of human resources practices in terms of factors such as stress, job satisfaction and absenteeism. Although employee satisfaction is considered a determinant of both customer satisfaction (as suggested by the service profit chain model (Heskett and Schlesinger, 1994)) and service quality (Evanschitzky et al., 2012), it seems that in the context of the call centre industry, this relationship is bidirectional in both cases. On the one hand, the literature suggests that even if employee satisfaction leads to service quality, the inverse of this relationship is negative. In other words, in the voice-to-voice encounter, most of the SERVQUAL dimensions seems to be negatively related to employee satisfaction (Maddern et al., 2007; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2010), mainly because managerial requirements on ensuring SERVQUAL metrics are considered extremely demanding by employees, causing emotional burnout and dissatisfaction (Rod and Ashill, 2013).

On the other hand, very few studies address the direct relationship between customer satisfaction and employee's satisfaction in the call centre environment (Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Upal and Dhaka, 2008). According to Upal and Dhaka (2008) the relationship is mutual and complex. For instance, it should be noted that in addition to employee satisfaction leading to customer satisfaction, customer feedback (in terms of recognition or abuse) can generate satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or emotional dissonance among employees (Litte and Dean, 2006; Poddar and Madupalli, 2012; Wegge et al., 2007). For example, when employees deal with problematic or demanding customers, the negative customer feedback is perceived as a lack of recognition, which leads to employee dissatisfaction or burnout. On the contrary, customer gratitude can lead to employee satisfaction. So, the relationship between customer and employee satisfaction is bidirectional in nature, and depending on the interaction, satisfaction may be achieved by both parts or by none. In addition, in the voice-to-voice encounter this relationship could also be affected by external factors, such as customer attitude toward the company (Sharma et al., 2009; Sharma, 2012), or employee commitment to the organization (Malhotra and Mukherjee, 2004; Sergeant and Frenkel, 2000). Therefore, dealing with customers or employees that display negative attitudes, could create a negative interaction between both parts, and consequently, to customer dissatisfaction (Helms and Mayo, 2008) or employee dissatisfaction (Wegge, 2006; Poddar and Madupalli, 2012). Additional employee outcomes can be considered in terms of whether the employee wishes to stay with the firm. In general, employee satisfaction promotes employee retention within the firm. Naturally, the more employees wishing to remain working at the call centre, the greater the knowledge and training, built up over time, will also remain within the firm.

Employee productivityIn the few studies that consider customer satisfaction in call centres, research focuses mainly on the key performance indicators (KPI) which include the following: service level (calls answered within a specific number of seconds), average speed of answer, average time in queue, average abandonment rate, percentage of first call resolution, adherence to schedule, average talk time, average after call work time, employee turnover rate, percentage of calls blocked, time before abandoning wait, inbound calls per agent, and total calls (Feinberg et al., 2000). But most of these indicators are extracted from the SERVQUAL model (Parasuraman et al., 1988) and are well established as the call centre's internal service quality metrics (Anton, 1997). These factors can be further classified as follows: employee behaviour (turnover rate, adherence to schedule), employee performance (service level, average speed of answer) and technology performance (average time in queue, abandonment rate), which in fact could be considered as part of service quality.

Customer satisfactionAlthough the main focus of our study is on customer satisfaction, as we have seen in the discussion of the literature, customer satisfaction is a complex topic. In order to fully appreciate the intertwining relationships between the variables that surround customer satisfaction, our analysis of the literature goes beyond satisfaction and includes a number of variables that are a consequence of satisfaction, such as customer behaviour and customer outcomes. Indeed, it is noteworthy that some research skips the customer satisfaction construct and connects customer behaviours directly to other business outcomes. For example, customer loyalty has been interpreted as consequence of the customer orientation approach adopted by call centre managers (Dean, 2007) or employee's empathy and trust (Keiningham et al., 2006). The customer orientation strategy is suggested as the source of customers’ trust and positive word of Walsh et al. (2012). Surprisingly given the results-orientation of call centres as industry, we found no study that addresses the link between customer satisfaction and call centre financial performance.

In general, customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction entails consequences that may be positive or negative. For instance, among the customer dissatisfaction outcomes are: take no action; take some private action such as quitting the service or spreading negative word of mouth; and take some public action, such as legal action or registering a complaint (Day and Bodur, 1978). Further supporting evidence about the likelihood of losing customers following a dissatisfactory experience has been gained from studies on customer service evaluation (Helms and Mayo, 2008; Levesque and McDougall, 1996). At the other extreme, customer loyalty, customer retention and positive word of mouth are considered positive customer satisfaction outcomes (Yi, 1990).

In the context of the call centre industry, little academic research has addressed customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Some authors simply endorse the generally held view that customer satisfaction leads to positive word-of-mouth, repeat purchase intention or loyalty (de Ruyter and Wetzels, 2000; Makarem, 2009; Sharma et al., 2009; Sharma, 2012). However, customer loyalty is not often an outcome of satisfaction in the context of call centres and is more likely to be attributed to the hassle factor in the case of services (such as financial services) where the switching cost is considered especially high or cumbersome (Panther and Farquhar, 2004). Other studies take a more negative perspective, by considering the customer dissatisfaction construct as a mediator between rude employees and customer defection (Helms and Mayo, 2008) or as a mediator between perceived service quality and complaining intention (Sharma et al., 2009).

Literature takeawaysAlthough the review of the literature points to a broad spectrum of cause and effect relationships that begin with managerial strategies and HR practices and end in customer outcomes, it should be noted that the specific order of the cause-effect relationships is not entirely clear. In this sense, it would be appropriate to further explore some of the intermediate and peripheral relationships. This analysis may be facilitated by identifying and analysing the classical models that integrate all these groups of variables, especially those that predict company performance. These models include the Lean Technique (Krafcik, 1988), the Balanced scorecard (Kaplan and Norton, 1992, 1998), Six sigma (Henderson and Evans, 2000; Welch et al., 2005), and the Service-Profit Chain model (SPC) (Heskett et al., 1997; Heskett and Schlesinger, 1994). However, most of these models require a qualitative approach (Lean Technique, Balanced scorecard, Six-sigma) whereas our dataset is quantitative. Many of these models were designed originally for the manufacturing industry, but have also been adapted for different service industries, including call centres (Piercy and Rich, 2009a; Halliden and Monks, 2005; Robinson and Morley, 2006; McAdam et al., 2009).

One recent study demonstrates that the Service Profit Chain model is suitable for analysing Call Centres in the International context (Chicu et al., 2016). Following this example, we tested the SPC model with our Spanish data set. However, the model did not fit and hence we do not present it here (this analysis is available on request from the authors). This outcome suggests that we should explore similar variables and consider the possibility of different directions in the relationships among the variables at the points where the original model was incongruent with the data. Hence, the authors decided to undertake an exploratory approach with the SPC model as a basis, in order to tease out the nature of the relationships between the variables. Indeed, the Service profit-chain (SPC) model requires a quantitative approach, and despite being designed especially for the service industry, academic research has focused mainly on the face-to-face encounter (Papazissimou and Georgopoulos, 2009; Silvestro, 2002; Yee et al., 2008, 2011), while overlooking the applicability of this model in the specific context of the voice-to-voice encounter.

MethodologyIn order to explore the complex relationships related to human factors that, according to the literature, lead to customer satisfaction in call centres, we used a sample of secondary data obtained from the Global Call Centre Research Project (Holman et al., 2007). The sample comprised of 109 Spanish call centres, including inbound and outbound, in-house and outsourced call centres from different industries, such as telecommunication, banking, insurance, transport, public administration, etc. The surveys were administered to the call centre manager or call centre HR manager via onsite visits or over the telephone.

Measures employedIn order to measure the various elements related to the human factors that we consider in the literature review, while keeping in mind the limitations implied by the use of a secondary dataset, we used the following measures for exploring the human factors that shape customer satisfaction in call centres.

Service quality. This construct is made up of various elements of the company's HR management practices. In the current study, this was measured using job characteristics that are especially relevant to call centre work quality, as explained in the literature review, focusing on the employees discretion and job design (Wood et al., 2006). Therefore, the two factors employed are:

- •

Discretion is modelled as a reflective factor and is measured by three indicators: the extent to which employees have discretion over work tasks, discretion over methods of work, and discretion over speed of work (all on a five-point Likert scale).

- •

Job design is modelled as a formative factor and is measured by: the percentage of employees working in self-managed or semi-autonomous teams, and percentage of employees with flexible working arrangements.

Training. As one of the key HR practices highlighted in the literature review as a determinant of customer satisfaction in call centres, training is a reflective construct and is measured by two indicators: formal training for typical core-employees in interpersonal or team-building skills, and number of days of formal training received per year by experienced core employees.

Employee outcomes. In order to measure this key aspect of the human factor in terms of how it responds to the policies put in place by the company, we take the two following central indicators:

- •

Employee satisfaction. As this was an organizational level survey, we followed the common practice of substituting the individual measure of employee satisfaction with organizational level proxy measures. Origo and Pagani (2008) suggest that employee satisfaction may be apprehended as any form of employee utility. In this regard, absenteeism is one of these measures. Indeed, in their meta-analysis, Scott and Taylor (1985) found a significant negative relationship between absenteeism and job satisfaction, indicating that this would be a good proxy. Similarly, and more specifically in the context of SPC studies, Hurley and Estelami (2007) found that employee turnover was just as good a measure as employee satisfaction in determining the relationship with customer satisfaction. This finding moved them to recommend the use of turnover rather than satisfaction as the former is a readily available measure in organizations as opposed to the significant costs involved in collecting employee satisfaction data. Following these recommendations, the variables employed as proxies for employee satisfaction in this study are: absenteeism (the percentage of employees absent on normal working days), and employee turnover (percentage of employees who quit in one year), both of which inverted into positive indicators. The construct of Employee Satisfaction is modelled as a reflective factor.

- •

Employee retention. Following Heskett and Schlesinger (1994) this construct was measured by two items: typical tenure of core employees and percentage of core employees with tenure more than five years. This was considered a reflective construct.

Employee productivity. This factor was measured by two common indicators of call centre employee productivity: percentage of calls answered within target time (Piercy and Rich, 2009b; Banks and Roodt, 2011) and number of calls a core employee handles per day. This factor was modelled as a formative construct.

Employee performance. This is a reflective construct measured by a single indicator, namely the percentage of performance achievement. This indicator was obtained by asking call centre managers about how, in their specific call centres, the overall performance of their employees was measured. This is a broader and more nuanced measure than employee productivity, such as typical call centre measures of abandoned calls, because it captures the specific requirements of what constitutes employee performance in each call centre surveyed.

Customer satisfaction. As this study involved an organizational level survey, customer satisfaction was a single measure obtained from the call centre manager, based on their customer satisfaction data and transformed into a five-point Likert scale. This construct was modelled as a reflective factor.

Firm performance. In line with Heskett and Schlesinger (1994) who proposed that the final link in the SPC is represented by the company's revenue growth, this study measured performance in terms of percentage by which value of sales increased or decreased over the last two year (Batt, 2002b, 2002a). This is considered a reflective construct.

Categorical variables were used as controls in order to reflect the strategy of the CC (in-house vs outsourced) and the main type of call (inbound vs outbound). In-house versus outsourced reflects the general strategy of the call centre as a business unit. This characteristic, which is often a managerial choice, may be simply a reflection of the ownership of the call centre, or it can also be seen as a proxy for managerial strategies of quality versus cost, service orientation versus production orientation. Inbound versus outbound reflects the nature of the service offered by the call centre.

Data analysis: the exploratory approachAccording to Jöreskog (1993), the general framework for testing structural equation models allows researchers to opt for modelling generator scenarios, which implies the rejection of a theoretical model on the basis of poor fit. Consequently, this study turned to PLS Graph to analyse the data. PLS Graph version 3.0 was used to test the measures and the model. In order to estimate the significance (t-value) of the relationship, we employed a bootstrap technique (Chin, 2003), which involves resampling the data set 1000 times (Efron and Tibshirani, 1994). The blindfolding procedure was carried out in order to obtain Stone-Geisser's Q2 (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974), which is expected to be greater than 0 in order to confirm the predictive relevance of the model (Wold, 1982, 1985).

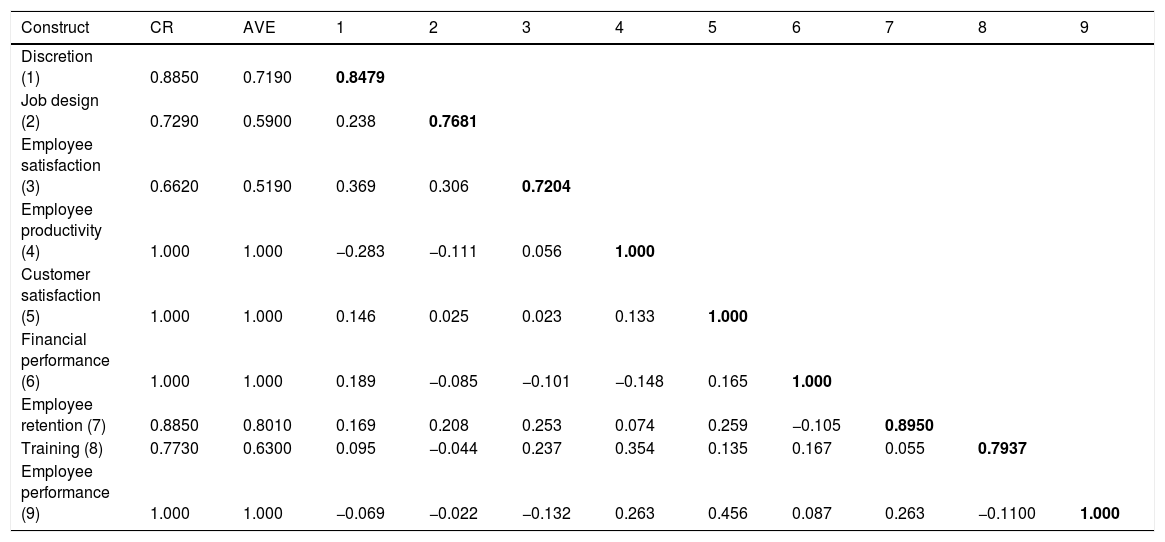

ResultsMeasurement model evaluationTo assess whether the latent constructs were consistently measured by observable variables, we checked for convergent and discriminant validity, as shown in Table 2. Convergent validity assesses the internal consistency for a given block of indicators by considering the composite reliability level (Werts et al., 1974). The composite reliability is only applicable for reflective indicators (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998) and according to Nunnally (1967) it should be greater than 0.7. Table 2 shows that most of the latent variables from our model meet this requirement.

Correlation matrix.

| Construct | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discretion (1) | 0.8850 | 0.7190 | 0.8479 | ||||||||

| Job design (2) | 0.7290 | 0.5900 | 0.238 | 0.7681 | |||||||

| Employee satisfaction (3) | 0.6620 | 0.5190 | 0.369 | 0.306 | 0.7204 | ||||||

| Employee productivity (4) | 1.000 | 1.000 | −0.283 | −0.111 | 0.056 | 1.000 | |||||

| Customer satisfaction (5) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.146 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.133 | 1.000 | ||||

| Financial performance (6) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.189 | −0.085 | −0.101 | −0.148 | 0.165 | 1.000 | |||

| Employee retention (7) | 0.8850 | 0.8010 | 0.169 | 0.208 | 0.253 | 0.074 | 0.259 | −0.105 | 0.8950 | ||

| Training (8) | 0.7730 | 0.6300 | 0.095 | −0.044 | 0.237 | 0.354 | 0.135 | 0.167 | 0.055 | 0.7937 | |

| Employee performance (9) | 1.000 | 1.000 | −0.069 | −0.022 | −0.132 | 0.263 | 0.456 | 0.087 | 0.263 | −0.1100 | 1.000 |

Square root of AVE on diagonal.

Discriminant validity was checked by using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), which is applicable only for reflective indicators (Barclay et al., 1995), and should be greater than 0.5 (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998). This requirement was fulfilled by all the constructs in the model. In addition, it is recommended that a construct has a good discriminant validity if the square root of the AVE for each construct is greater than the correlation between the construct and any other construct in the model (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998; Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As we can see in Table 2, all the constructs estimated in the model meet this condition, as any of the elements in the matrix exceeded the respective diagonal element. Thus, the discriminant validity of the estimated model is confirmed.

Structural model evaluationAs PLS is a variance-based technique, Chin and Marcoulides (1998) suggest that we may assess the predictive capacity by considering the R-square for dependent latent variables (Cohen, 1988), the Stone-Geisser Q2 (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974) and the average variance extracted (AVE) developed by Fornell and Larcker (1981). R-square is extracted from the inner path model and is expected to reach 0.67 value for substantial significance, 0.33 for moderate level and 0.19 for weak level (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998). In our case, all the constructs are below the minimum required level, and the only construct reaching only the weak level is employee satisfaction (R-square=0.21).

The Stone-Geisser Q2 (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974) was obtained by carrying out the blindfolding procedure that is expected to be greater than 0 (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998; Wold, 1982). Therefore, the cross-validated communality for this model was 0.42, confirming that the predictive capacity of the model is relevant. Also, the average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from 0.51 to 0.80, which means that at least 50% of the indicator's variance is explained (Chin and Marcoulides, 1998; Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated model, including the path coefficients as well as the t-values obtained from the bootstrapping method in PLS. As suggested by Chin and Marcoulides (1998), the standardized path should be at least 0.20 in order to be considered meaningful. As we can see in Figure 1, both Discretion as well as Job Design, are significantly related to Employee Satisfaction at p<0.001 (t-statistic=3.78) and p<0.01 (t-statistic=2.87), respectively. The effect of Training on Employee Productivity is also significant, p<0.001 (t-statistic=3.70). In turn, Employee Productivity is significantly related to Employee Satisfaction at p<0.01 (t-statistic=2.61), as well as to Employee Performance at p<0.005 (t-statistic=2.00). All the same, both Employee Satisfaction (at p<0.01 and t-statistic=2.66) as well as Employee Performance (at p<0.001 and t-statistic=2.81) lead to Employee Retention. Subsequently, Employee Retention leads to Customer Satisfaction (at p<0.01 and t-statistic=2.69). Finally, Customer Satisfaction is significantly related to company results (p<0.005 and t-statistic=1.97).

Additionally, we ran the model with the two categorical variables that were outlined earlier in the methodology section, i.e., inbound versus outbound (calls) and in-house versus outsourced (call centre). However, no significant results were obtained from the analysis because of the limitations imposed by the sample size. Furthermore, we ran the same adjusted model with only inbound and then only outbound, with only in-house and only outsourced. Yet once again the small sample size limited any meaningful results. The model showed the same relations but none of which were significant.

DiscussionIn this paper, we set out to investigate the role of the call centre employee in generating customer satisfaction, as research to date has not yet focused on this issue in the call centre context. This is an important issue because of the essential role of the call centre in driving and maintaining customer satisfaction. However, research has not yet adequately considered the relationship between employee agency and customer-related outcomes in the context of the call centre.

In order to undertake this study, we explored the employee-related paths that lead to customer satisfaction. Our review of the literature explored the factors surrounding and shaping customer satisfaction in call centres. We noted that the specific order of the cause and effect of employee-related factors on customer satisfaction is not yet a clear-cut issue. To investigate these complex relationships more carefully we initially considered established models such as the Service-Profit Chain, which has previously been tested on the call centre sector in other national contexts (Chicu et al., 2016). However, the reality of Spanish call centres did not accurately match this model and merited the exploration of a more nuanced system of relationships. Therefore, we adopted a theory building approach aided by PLS analytical methods. In the following section we outline the results of this analysis.

Summary of resultsIn the first block of relationships, we explored the interactions between HR policies and practises (job design, discretion, training, team work, etc.) and the most immediate outcomes in terms of employee satisfaction and productivity. We disentangled these relationships in the following way: Employee satisfaction is not the only outcome of positive HR practices. Some HR practices, such as job design and job discretion, may lead to employee satisfaction. Others, such as training, lead to employee productivity, rather than satisfaction. In turn, employee productivity is significantly related to employee satisfaction. Hence, our study shows that these relationships are rather more complex and intertwined than some other established models would suggest.

The next block of relationships relates to the factors that lead to employee retention. Once again, we note the presence of more nuanced relationships, whereby employee satisfaction encourages employees to remain in a company (a crucial aspect of the call centre sector, characterised by high levels of employee turnover), yet does not necessarily encourage productivity. Subsequently, on the one hand, employee retention is the main indicator that mediates the relationship between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction. On the one hand, employee retention also mediates between employee productivity and employee performance, and customer satisfaction. The final link of the model shows that customer satisfaction leads to call centre revenue growths. This relationship has been observed in our study, although with limited strength.

ContributionsA contribution of this study is to caution researchers who deal with employee–customer encounters, that the relationships they study are not as simple as they might necessarily be envisaged. This is especially relevant for any topic that intends to connect HR and Marketing. In this section, we discuss the main findings with which this study contributes.

Our study suggests that investing in training employees will pay off in terms of customer satisfaction, but that the link is not a simple linear one. What our study demonstrates is that customer satisfaction is achieved as a result of employees being satisfied in their jobs and that this satisfaction is a result of investment in training and upskilling employees. By investing in training employees, employee productivity is directly impacted and this, in turn, impacts on employee satisfaction. This finding is in line with Porter and Lawler's seminal work (1968), in the sense that employee productivity depends on the employee's ability to perform the task. It is useful here to discuss the AMO framework, which has been widely accepted in the HRM literature for explaining the linkage between human resources practices and performance (Boxall and Purcell, 2003). In this model, performance is a function of capacity/ability to perform (in our study, achieved by training), willingness/motivation to perform (in our study, satisfaction) and opportunity to perform (in our study, discretion and other characteristics of job design) (Blumberg and Pringle, 1982). Therefore, investing in HR practices, particularly in terms of training, will assist employees in task performance and will result in more satisfied employees. This finding has important implications for those charged with the management of call centres. One of the ways in which employees can be more productive and thus more satisfied is by investing in training and developing employees. And ultimately this will lead to an increase in customer satisfaction levels. Furthermore, this also concurs with previous research that positive HR practices will improve employee's ability to deliver service quality (Litte and Dean, 2006) and that HR practices based on employee training and appraisal will improve service quality as well as customer satisfaction (Curry and Lyon, 2008).

A further contribution of our study is the identification of a weak relationship between customer satisfaction and the financial performance of the call centre. This merits some reflection: Firstly, in the case of call centres, the “hassle factor” involved in complaining or in changing service provider is significant (Panther and Farquhar, 2004). Consequently, most customers, even those who are unsatisfied, do not take any action. In other words, some customers become loyal not because they experience satisfaction, but because they face difficulties or additional costs when changing service provider. Therefore, customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction might not have a considerable effect on call centre financial performance. Secondly, it seems that in the context of the call centre, employees often deal with angry and dissatisfied customers (Helms and Mayo, 2008). In this sense, an alternative route to company growth and performance may be managing customer dissatisfaction rather than satisfaction (Levesque and McDougall, 1996). Therefore, in the call centre sector we may not expect strong levels of satisfaction among customers, but nevertheless it is important to focus on minimizing their dissatisfaction.

Limitations and future researchThere are a number of limitations of this study that should be noted. Firstly, because we employ secondary data, we did not have all of the variables that could have benefitted our analysis and that would encompass all of the dimensions outlined in Table 1. In this sense, future research may also consider developing measures of service quality that are specific to call centres. This should distinguish between technology and human service encounters (Dean, 2008; Ellway, 2014), in line with a tried and tested service quality measurement tool (such as SERVQUAL), but adapted to the specific context of call centres.

Secondly, this is an organizational level study that gathers data from a single respondent. While this has some inherent advantages in terms of internal coherence and access to a knowledgeable informant, future research should consider testing this model by collecting the data from different informants, such as employees, customers and call centre managers, and at different levels of unit of analysis.

Given the finding on the central role of employee retention in generating customer satisfaction, we believe that further research of a qualitative nature should be conducted to establish what methods call centres are using to retain employees. The dissemination of best practice in this area would be of value to all those in this sector. Additionally, the finding that the AMO framework is of use in understanding the link between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction is worthy of further investigation to establish if the framework can deliver improved performance in the call centre setting.

Finally, this study does not consider that the relationship between employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction could also be reciprocal. According to some authors, customer feedback, in terms of recognition or abuse, can generate satisfaction, dissatisfaction, or emotional dissonance among employees (Litte and Dean, 2006; Poddar and Madupalli, 2012; Wegge et al., 2007). Therefore, the relationship between customers and employees is mutual, and depending on the interaction, satisfaction can be achieved by both parts, or neither of them. Therefore, future research should draw on the contributions that have been made into phenomena such as customer rage and incorporate them into studies that consider both directions simultaneously.

Concluding thoughtsIn terms of management takeaways, it is important to note that this study encourages us to reflect upon the importance of a whole range of factors across the entire business process. In other words, the traditional separation of the functions of business may hinder the realisation that policy decisions in HR will have real consequences for Marketing and vice-versa. In this sense, we would encourage the development of further cross discipline models, like the one proposed by this study, that facilitate a more holistic view of processes across the entire business.

In conclusion, the sustained growth experienced in online retail and services, suggests that, as consumers, more and more of our purchases (in ever more product categories) are made online. Therefore, we will increasingly deal with customer support in the online realm, mostly through call centres and online help desks. This means that traditional face-to-face encounters between employees and customers will be replaced by online, technology mediated service encounters. Hence, customer satisfaction will become increasingly dependent on virtual encounters through call centres, necessitating greater knowledge and understanding of how customer satisfaction is manifested in an environment that is commonly associated with negative experiences rather than customer satisfaction. Indeed, we still know relatively little about human interactions in technology-mediated versus traditional offline environments. This is likely to change as we learn to interact online and on the telephone, and as we develop new technologies to do so.