This paper examines the determinants of perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the Chilean pension funds industry. Results show that price consciousness and brand credibility are positively associated with perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by pension fund contributors. Results also show that financial literacy is only positively associated with actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Additionally, results show that price based advertising exposure is only positively associated with perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. This association is stronger for contributors with a high use of the price-quality cue. Based on the findings presented, implications for managers, regulators and researchers are drawn.

Frequently, managers, regulators and researchers use common assumptions to analyze and discuss the effects of price on the consumer decision making process, and which strategies the firms should use in order to set prices and to communicate them to customers. One such assumption is that customers know (to a reasonable degree) the prices of the goods and services they purchase (Frank, 2006). However, studies examining customers price knowledge have revealed that while the customer may possess accurate knowledge of prices in certain categories, customer knowledge of prices varies significantly across various product categories and in some cases may be far below levels required for optimal decision making (Dickson and Sawyer, 1990; Estelami and Lehmann, 2001). Despite the practical significance of a customer's price knowledge, few studies on price knowledge are existent and most of the existing research has focused purely on manufactured goods (Estelami, 2005; Rödiger and Hamm, 2015). Published studies of price knowledge in services are far less frequently available and little is known about the level of price knowledge for services in general, and financial services in particular (Estelami, 2005).

In Chile, pension fund providers (administradoras de fondos de pensiones, AFPs) are firms with the exclusive objective of managing pension funds, along with the provision of all benefits and guarantees established by law. As a retribution for its services, these firms charge a commission to each of its contributors in order to finance its activities. A pension funds provider is required (by regulation) to charge the same variable commission over taxable salary to all of their contributors. In the Chilean pension funds industry, Hidalgo et al. (2008) demonstrated that matching the industry's price leader reduced the firm's profits, and thus diminished the firm's incentive to offer the lowest commission rates. They comment that contributors do not exhaustively search for information about commission paid nor do they evaluate commission paid in the Chilean pension funds industry. Hidalgo et al. (2008) suggest that contributors are passive information receivers. As a result, the level of knowledge contributors have about commission paid to their pension fund providers is quite limited. This lack of knowledge surrounding commission paid serves as a catalyst for creative and sometimes manipulative marketing practices. In contrast, high levels of knowledge surrounding commission paid would make a contributor capable of understanding and assessing diverse offers from pension fund providers.

Empirical evidence suggests the existence of ample variance in terms of price knowledge across both consumers and firms (Estelami et al., 2001; Olavarrieta et al., 2012; Samoggia, 2016). Consequently, how valid it is to treat contributors and pension fund providers in the same homogenous group is questionable because in practice it is likely that they both have varying important characteristics, which may have implications for the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. If these characteristics influence the knowledge of commission paid by contributors, managers and regulators need to understand those differences in order to create and to regulate pricing strategies in the pension funds industry.

This paper examines the determinants of perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the Chilean pension funds industry. An empirical study utilizing a survey administered through personal in-home interviews has been carried out. The study uses this data to measure the knowledge of commission paid – the dependent variable – and to estimate models of price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure as the explanatory variables. This approach is consistent with earlier studies on customer's price knowledge (e.g., Conover, 1986; Dickson and Sawyer, 1990; Estelami and De Maeyer, 2004; Le Boutillier et al., 1994; Olavarrieta et al., 2012; Vanhuele and Drèze, 2002). This study measures actual knowledge of commission paid, that is, what contributors actually know, as well as perceived knowledge of commission paid, that is, what contributors think they know about commission paid in the context of the Chilean pension funds industry. Both knowledge constructs were included in the study since past research has shown that what customers think they know is not always a good indicator of their actual knowledge (Gaston-Breton and Raghubir, 2014; Mägi and Julander, 2005).

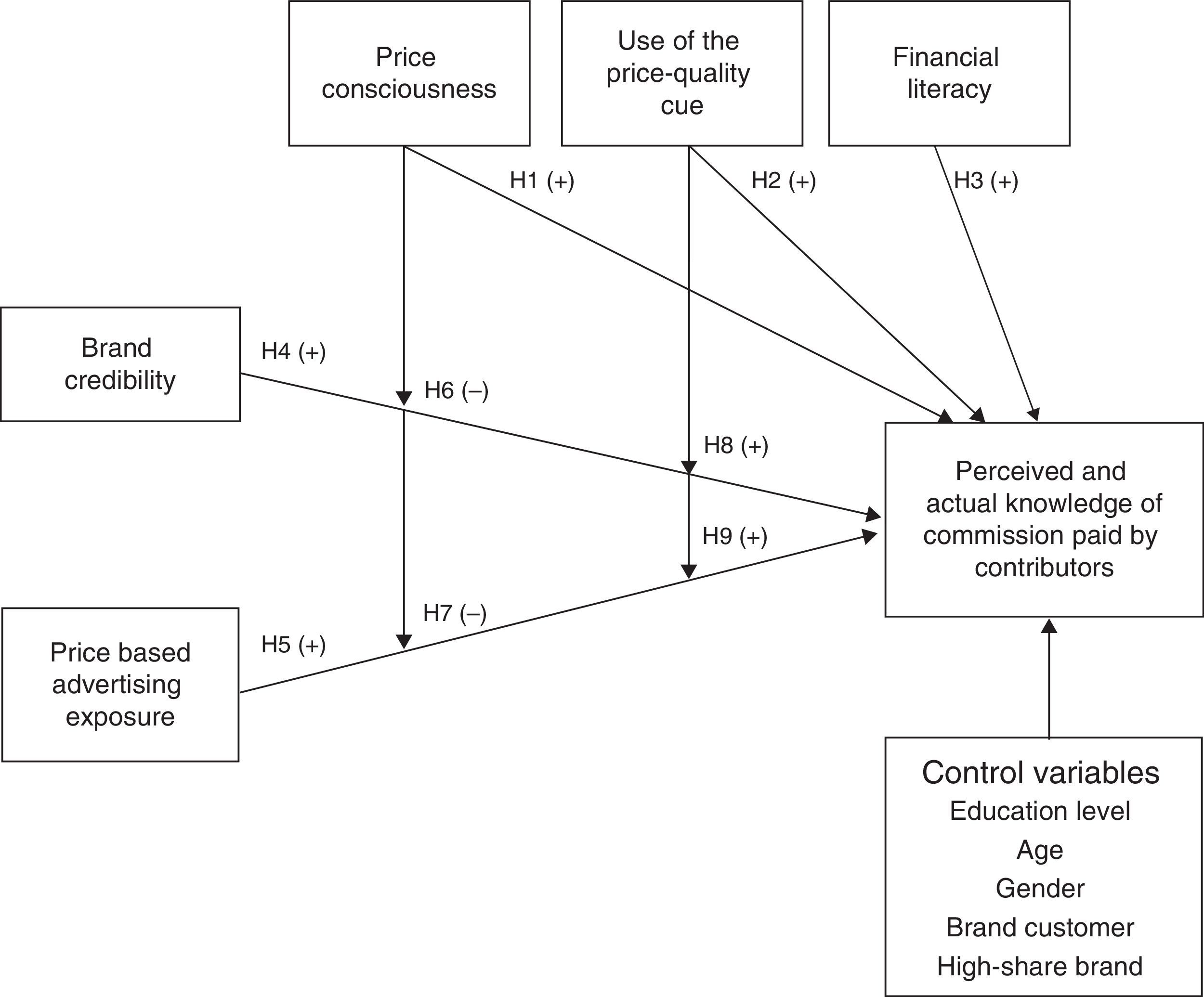

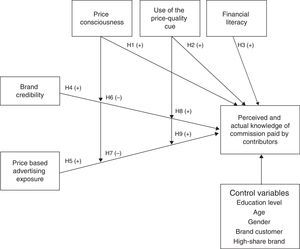

Conceptual frameworkThe review of the literature and the hypothesis development follows the structure of the framework shown in Fig. 1. This section reviews the literature to derive hypotheses about the effects of price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure on perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the Chilean pension funds industry.

The effects of price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue and financial literacy on the knowledge of commission paid by contributorsPrevious studies define price consciousness as the degree to which the consumer focuses exclusively on paying a low price (Alford and Biswas, 2002; Jung et al., 2014). Highly price-conscious consumers usually attempt to minimize the price paid and typically face lower price search costs due to enhanced psychological (e.g., enjoyment) and economic (savings) benefits from conducting price search than less price-conscious individuals, and therefore engage in higher levels of price search (Alford and Biswas, 2002; Kukar-Kinney et al., 2007). Consequently, highly price-conscious consumers process more price information than less price-conscious customers (Le Boutillier et al., 1994; Gauri et al., 2008). Previous studies of manufactured goods show a positive relationship between price consciousness and the level of actual price knowledge (e.g., Jensen and Grunert, 2014; Olavarrieta et al., 2012). Thus, highly price-conscious contributors could regularly beat the market, by knowing when and where to hire the services of a pension fund provider, which is derived from an accurate knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Hence:H1 Price consciousness is positively associated with (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

Price plays two distinct roles in a consumer's evaluation of product alternatives: as a measure of sacrifice (i.e., amount of money customer must sacrifice) and as an informational cue (i.e. quality and status inference) (Völckner, 2008). Price could influence ones image or opinion of a pension fund provider. Research in pricing has established that when quality is unclear, price is used by individuals as more than a simple measure of monetary sacrifice, and is often used as a proxy for quality (Dodds et al., 1991). The complexity of the pension funds and its associated components (e.g., pension fund's assets and return on investment, customer service) further complicate the notion of quality, thereby increasing reliance on simpler quality cues, such as commission paid by contributors (Sivakumar and Raj, 1997). Although the relationship between price and quality may be a true reflection of objective quality variations, it is also often a result of the inability of the consumer to objectively determine quality using any source of information other than price itself (Monroe, 2003). In such circumstances, a consumers use of price as an indicator of quality would imply that price information might be of considerably higher diagnostic value than simply a determinant of monetary sacrifice. This increases the value of price knowledge and promotes additional incentives for customers to develop a working memory for prices (Estelami and De Maeyer, 2004). Measuring only perceived price knowledge, Estelami (2005) show that the use of the price-quality cue increases price knowledge. Therefore, one might expect a positive relationship between contributor's use of the price-quality cue and the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Hence:H2 Use of the price-quality cue is positively associated with (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

Financial literacy has implications for contributor's knowledge of commission paid. Bernheim (1995) was the first to point out not only that most individuals cannot perform very simple calculations and lack basic financial knowledge but also that the saving behavior of many customers is dominated by crude rules of thumb. Stango and Zinman (2009) show that those who are not able to correctly calculate interest rates out of a stream of payments end up borrowing more and accumulating lower amounts of wealth. Banks and Oldfield (2007) find that financial literacy is strongly correlated to people's understanding of pension arrangements. Therefore, one might expect a positive relationship between financial literacy and the knowledge of commissions paid by contributors. Hence:H3 Financial literacy is positively associated with (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

Brand credibility refers to the degree to which the consumer trusts the information offered by the brand (Brexendorf et al., 2015; Chang and Wu, 2014; Erdem and Swait, 1998). Consumers frequently use brand credibility to cope with uncertainty in their decision making (Akdeniz et al., 2013). Erdem et al. (2002) propose that brand credibility represents the cumulative effect of the credibility of all previous marketing actions (e.g., pricing) taken by that brand. Brand credibility is the believability of the information that the brand market, which requires that consumers perceive that the brand has the ability and willingness to continuously deliver what it says it will as promised. If contributors believe in the brand of the pension fund provider, contributors will have confidence in the information about commission paid by contributors offered by the brand of the pension fund provider, increasing the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Hence:H4 Brand credibility is positively associated with (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

Measuring only perceived price knowledge, Estelami (2005) shows that price based advertising has a positive effect on price knowledge. Price based advertising may result in the development of more precise knowledge of prices (Jacoby and Olson, 1977; Sawyer, 1975). According to adaptation level theory (Helson, 1964), exposure to market information through mechanisms such as advertising can help produce a database of information in customer's memory. These memorized data is then utilized in evaluating product offers (Winer, 1986). Increasing the level of customer exposure to price based advertising is therefore likely to help make consumers more price knowledgeable. The multiple-store theory of human memory (Lindsay and Norman, 1972) also suggests that increased exposure to advertisements is associated with a higher likelihood of the customer elaborating on the presented information. The result of this is the strengthening of memory traces through the movement of information from short-term to long-term memory, leading to higher levels of price knowledge (Vanhuele and Drèze, 2002). Thus, the presentation of information about commission paid by contributors in advertisements is likely to contribute to the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Hence:H5 Price based advertising exposure is positively associated with (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

In addition to directly affecting the knowledge of commission paid by contributors, price consciousness could moderate the impact of brand credibility and price based advertising exposure. Price consciousness is the degree to which consumers are motivated to seek out price information regarding particular offerings (Naidoo and Hollebeek, 2016). Highly price-conscious consumers seek price information regardless of how easily accessible it is. Conversely, less price-conscious consumers engage less easily in price information searching. Less price-conscious consumers normally are looking for cues that would help them reduce the price search (Gauzente and Roy, 2012; Kukar-Kinney et al., 2007). Less price-conscious consumers generally seek only easily accessible price information (Miyazaki et al., 2000; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986). Price based advertising along with brand credibility provide consumers with easier access to price information that they believe. Thus, increasing brand credibility and price based advertising exposure is expected to have a greater effect among contributors who not very price conscious. Hence:H6 The relationship between brand credibility and (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors is stronger among contributors who have lower price consciousness rather than a high price conscious. The relationship between price based advertising exposure and (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors is stronger among contributors who have lower price consciousness rather than a high price conscious.

Besharat et al. (2016) comment that the use of the price-quality cue could significantly influence the effects of many marketing strategies. In addition to directly affecting the knowledge of commission paid by contributors, the use of the price-quality cue could moderate the effects of brand credibility and price based advertising. The use of the price-quality cue would imply that price information might be of considerably higher diagnostic value than simply a determinant of monetary sacrifice. This increases the value of price information for contributors who use of the price-quality cue regularly. Consequently, increasing brand credibility and price based advertising exposure is expected to have a greater effect among those contributors who use the price-quality cue more regularly. Hence:H8 The relationship between brand credibility and (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors is stronger among those contributors who use the price-quality cue most regularly. The relationship between price based advertising and (a) perceived and (b) actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors is stronger among those contributors who use the price-quality cue most regularly.

Education level, age, gender, brand customer, and high-share brand were used as control variables. The benefits and costs of the knowledge of commission paid by contributors suggest three demographic characteristics of contributors: education level, age, and gender. These three control variables are major segmentation variables used in marketing (Castilla and Haab, 2013; Olavarrieta et al., 2012). Education links to thinking costs (Raju, 1980; Urbany et al., 1996). Regarding contributor's ability to acquire knowledge regarding commission paid, it is reasonable to suggest that it would increase with the level of formal education. Age links to search and thinking costs (Martínez and Montaner, 2006; Urbany et al., 1996). Cole and Balasubramanian (1993) found that older consumers searched less intensely and less accurately than younger consumers did. Gaston-Breton and Raghubir (2013) found that older shoppers were less able to complete memory based tasks than younger shoppers were. Consequently, older contributors could be less involved in the search for information around commission paid to pension fund providers than younger contributors, on average, contributing to age differences in the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Gender links to thinking costs (Darley and Smith, 1995; Milner and Higgs, 2004). In cognitive studies, it is widely accepted that women excel in verbal skills, whereas men show superiority in mathematical ability (Kim et al., 2007). Thus, men could be more involved in information about commission paid to pension funds providers than women, on average, contributing to gender differences in the knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Additionally, brand customer and high-share brand were included as control variables. Brand customers have higher and more recent exposure to prices, reflected with their superior price knowledge. Low-share brands often suffer from low brand awareness across individuals (Farías, 2015; Manzur et al., 2012). Thus, individuals are likely to ignore information offered by low-share brands.

Research designSampleAn empirical study utilizing a survey administered through 640 personal in-home interviews is carried out. Recognizing that various parts of the country may have differences regarding pension fund providers and contributor characteristics in the Chilean pension funds industry and due to practical limitations, the survey includes only participants in Santiago, the capital of Chile. The target population are prospective (i.e., who plans to hire a pension fund provider within next three months) and current contributors aged 18 years and over in a household in Santiago. All participants were personally surveyed face-to-face in 2015 by trained interviewers. All interviews were carried out at the household of the respondent. The sampling method was stratified (commune), randomized in each of its three stages (block, household, interviewed). The initial sample size was 1070. After the filter questions, the final sample size was 640 personal in-home interviews. With a confidence level of 95 per cent, the maximum level of sampling error is below 4 per cent.

MeasuresThe survey instrument is a questionnaire based on the literature review. The interviewer points to a university lapel label and says: “Excuse me, I am from ______ University. May I ask you questions about financial services?” Filter questions were used to establish whether a respondent was contributor in the pension funds industry. If the respondent was not a contributor, an additional filter question was used to establish whether the respondent planned to hire a pension fund provider within next three months.

A complete list of items appears in Appendix A. Existing scales were used for item generation. All materials were translated into Spanish using a double translation procedure, which is proven to be one of the best ways to provide validity to this process (McGorry, 2000). This paper distinguishes between two kinds of customer's knowledge of commission paid by contributors: actual and perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Participants reported actual knowledge of commission paid for two brands of pension fund providers (a high-share brand: Provida, and a low-share brand: Planvital) in the Chilean pension funds industry. Consequently, a total of 1280 (640×2) observations were collected to measure actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. The study uses this data to measure actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors (accuracy of knowledge of commission paid within 0.5% variation of the actual commission paid) – the dependent variable – and to estimate hierarchical logistic regression models with price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure as the explanatory variables. This approach is consistent with earlier studies on customer's price knowledge (e.g., Conover, 1986; Damay et al., 2014; Dickson and Sawyer, 1990; Estelami and De Maeyer, 2004; Le Boutillier et al., 1994; Olavarrieta et al., 2012; Vanhuele and Drèze, 2002). Additionally, perceived (self-reported) knowledge of commission paid is measured with three items (Estelami, 2005). Consequently, a total of 640 observations were collected to measure perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. The study uses this data to estimate hierarchical regression models with price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure as the explanatory variables. All statistical analyses were undertaken with IBM SPSS software version 21.

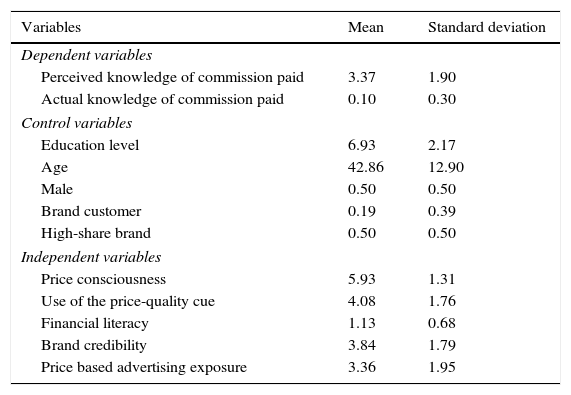

ResultsTable 1 shows the descriptive statistics. The average age of the sample was 43. The sample was 50 per cent female. These demographic characteristics reveal a sample that closely resembles the underlying population from which it is drawn. The average age of contributors in the Chilean pension funds industry is 38 and the population is 51 per cent female (Farías, 2014). The multi-item Likert scales exhibit high reliability levels, indicated by coefficient alphas which all exceed 0.7. The multi-item Likert scale values for each of the constructs were determined by computing the mean of the individual items on that scale. The resulting Likert multi-item scale measures therefore range from a low of 1 to a high of 7.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Perceived knowledge of commission paid | 3.37 | 1.90 |

| Actual knowledge of commission paid | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Control variables | ||

| Education level | 6.93 | 2.17 |

| Age | 42.86 | 12.90 |

| Male | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Brand customer | 0.19 | 0.39 |

| High-share brand | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Independent variables | ||

| Price consciousness | 5.93 | 1.31 |

| Use of the price-quality cue | 4.08 | 1.76 |

| Financial literacy | 1.13 | 0.68 |

| Brand credibility | 3.84 | 1.79 |

| Price based advertising exposure | 3.36 | 1.95 |

The independent variables employed in the study were mean-centered before creating the interaction terms to minimize multicollinearity. The data was employed in a series of hierarchical regression analyses to estimate the path coefficients for the hypothesized relationships. In each regression, education level, age, gender, and brand customer were controlled in order to see if the hypothesized effects accounted for variance in perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors over and above these control variables.

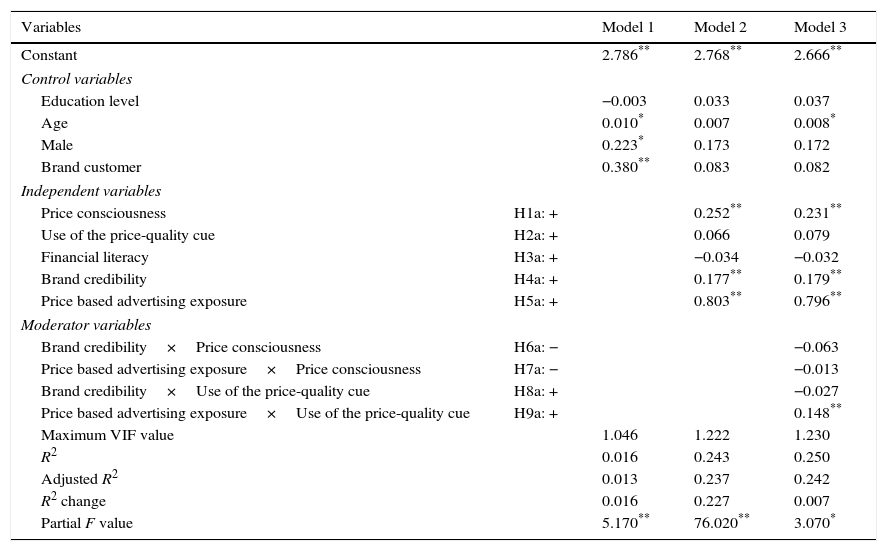

The results of the hypotheses tests are shown in Table 2. To begin, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for each regression coefficient range from a low of 1.004 to a high of 1.230, suggesting that the variance inflation factors in each regression are at acceptable levels (Hair et al., 2006). As Table 2 summarizes, the Model 1 regression analysis results indicate that the control variables explain only 1.6% of the variance in perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Adding the linear terms of price consciousness, use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure in Model 2 increased the R2 value by 22.7% (ΔF=76.020, p<0.01). Model 2 shows that price consciousness, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure are positively related to perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Consequently, H1a, H4a and H5a are supported. Conversely, the results suggest that the use of price-quality cue and financial literacy are not related to perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Consequently, H2a and H3a are not supported.

Regressions predicting perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.786** | 2.768** | 2.666** | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Education level | −0.003 | 0.033 | 0.037 | |

| Age | 0.010* | 0.007 | 0.008* | |

| Male | 0.223* | 0.173 | 0.172 | |

| Brand customer | 0.380** | 0.083 | 0.082 | |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Price consciousness | H1a: + | 0.252** | 0.231** | |

| Use of the price-quality cue | H2a: + | 0.066 | 0.079 | |

| Financial literacy | H3a: + | −0.034 | −0.032 | |

| Brand credibility | H4a: + | 0.177** | 0.179** | |

| Price based advertising exposure | H5a: + | 0.803** | 0.796** | |

| Moderator variables | ||||

| Brand credibility×Price consciousness | H6a: − | −0.063 | ||

| Price based advertising exposure×Price consciousness | H7a: − | −0.013 | ||

| Brand credibility×Use of the price-quality cue | H8a: + | −0.027 | ||

| Price based advertising exposure×Use of the price-quality cue | H9a: + | 0.148** | ||

| Maximum VIF value | 1.046 | 1.222 | 1.230 | |

| R2 | 0.016 | 0.243 | 0.250 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.013 | 0.237 | 0.242 | |

| R2 change | 0.016 | 0.227 | 0.007 | |

| Partial F value | 5.170** | 76.020** | 3.070* | |

Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported.

Adding the interaction terms in Model 3 increased the R2 value by 0.7% (ΔF=3.070, p<0.05). Model 3 show that H6a and H7a are not supported because data do not allow the assertion that the effects of brand credibility and price based advertising exposure on perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors are moderated by price consciousness. Similarly, the results show that the effect of brand credibility on perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors is not moderated by the use of the price-quality cue. Therefore, H8a is not supported (see Table 2; ps>0.10). Conversely, Model 3 show that the effect of price based advertising exposure on perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors is stronger for individuals with a high use of the price-quality cue (p<0.01). Thus, H9a is supported.

Determinants of actual knowledge of commission paid by contributorsAbout 10.3% of the responses in the sample show an accuracy of knowledge of commission paid within 0.5% variation of the actual commission paid. These data clearly indicate that contributors paid low attention to commission paid to pension fund providers in the Chilean pension funds industry.

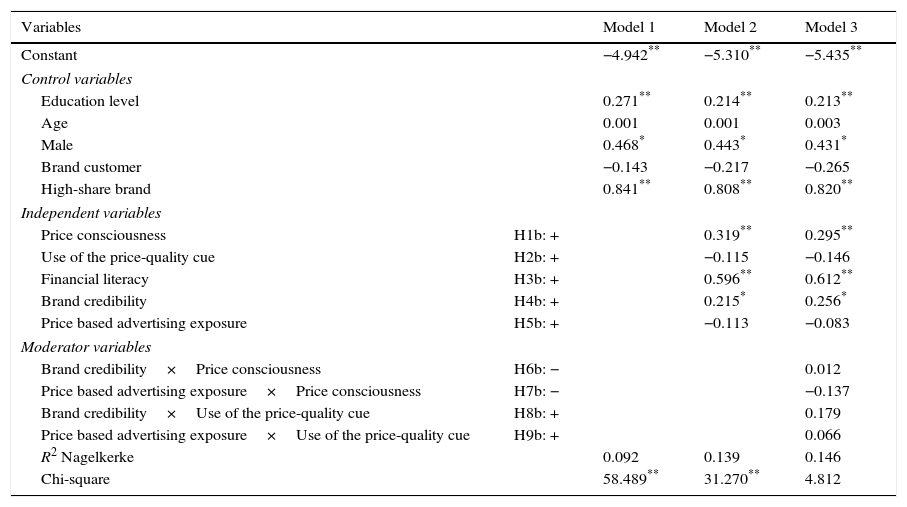

The hypothesized effects on actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors were analyzed using hierarchical logistic regression analyses. In each regression, education level, age, gender, brand customer, and high-share brand were controlled in order to see if the hypothesized effects accounted for variance in actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors over and above these control variables. The results of the hypotheses tests are shown in Table 3.

Regressions predicting actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −4.942** | −5.310** | −5.435** | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Education level | 0.271** | 0.214** | 0.213** | |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Male | 0.468* | 0.443* | 0.431* | |

| Brand customer | −0.143 | −0.217 | −0.265 | |

| High-share brand | 0.841** | 0.808** | 0.820** | |

| Independent variables | ||||

| Price consciousness | H1b: + | 0.319** | 0.295** | |

| Use of the price-quality cue | H2b: + | −0.115 | −0.146 | |

| Financial literacy | H3b: + | 0.596** | 0.612** | |

| Brand credibility | H4b: + | 0.215* | 0.256* | |

| Price based advertising exposure | H5b: + | −0.113 | −0.083 | |

| Moderator variables | ||||

| Brand credibility×Price consciousness | H6b: − | 0.012 | ||

| Price based advertising exposure×Price consciousness | H7b: − | −0.137 | ||

| Brand credibility×Use of the price-quality cue | H8b: + | 0.179 | ||

| Price based advertising exposure×Use of the price-quality cue | H9b: + | 0.066 | ||

| R2 Nagelkerke | 0.092 | 0.139 | 0.146 | |

| Chi-square | 58.489** | 31.270** | 4.812 | |

Note: Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported.

As Table 3 summarizes, the Model 1 regression analysis results indicate that the control variables explain 9.2% of the variance in actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Adding the linear terms of price consciousness, use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure in Model 2 increased the R2 value to 13.9% (Chi-square=31.270, p<0.01). Model 2 shows that price consciousness, financial literacy and brand credibility are positively related to actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Consequently, H1b, H3b and H4b are supported. Conversely, the results suggest that the use of the price-quality cue and price based advertising exposure are not related to actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Consequently, H2b and H5b are not supported.

Adding the interaction terms in Model 3 increased the R2 value to 14.6% (Chi-square=4.812, p>0.10). Model 3 show that H6b, H7b, H8b and H9b are not supported because data do not allow the assertion that the effects of brand credibility and price based advertising exposure on actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors are moderated by price consciousness and/or the use of the price-quality cue (see Table 3).

DiscussionPast price knowledge studies for manufactured goods (e.g., Dickson and Sawyer, 1990; Olavarrieta et al., 2012; Vanhuele and Drèze, 2002) suggest that less than half of the customers know the price of products they purchased. Consistent with these studies, this paper shows that contributors do have heterogeneous knowledge levels of commission paid to pension fund providers in the Chilean pension funds industry. The results show that only 10.3% of the sample shows an accuracy of knowledge of commission paid within 0.5% variation of the actual commission paid.

This paper also examines the influence of price consciousness, the use of the price-quality cue, financial literacy, brand credibility and price based advertising exposure on contributor's perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid to pension fund providers in the Chilean pension funds industry and tests the hypothesized relationships. This study shows that perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors are driven by different factors.

Consistent with Estelami (2005), this study show that price based advertising exposure has a positive effect on perceived knowledge of commission paid by contributors. This study contributes to the existing literature by showing that perceived knowledge of commission paid is also positively associated with price consciousness and brand credibility. The results also suggest that the effect of price based advertising exposure on perceived knowledge of commission paid is stronger for individuals with a high use of the price-quality cue.

Consistent with previous studies for manufactures goods (e.g., Jensen and Grunert, 2014; Olavarrieta et al., 2012), this study show that price consciousness has a positive effect on actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. This study contributes to the existing literature by showing that actual knowledge of commission paid is also positively associated with financial literacy and brand credibility. Additionally, the data does not support the idea that the effects of brand credibility and price based advertising exposure on actual knowledge of commission paid depends on price consciousness or the use of the price-quality cue.

Implications for managers and regulatorsBefore driving any public policy and managerial implications, regulators and managers will need to test and check contributor's knowledge of commissions paid and the antecedents that may influence it. Some insights from this study may help this search. This information can be very useful for both designing adequate and ethical marketing strategies, but also for designing choice environments that are fair and more adequate for social well-being. Promoting and improving price consciousness, financial literacy and brand credibility may definitely improve contributor's actual knowledge of commission paid.

Price consciousness, which denotes the degree to which contributors are motivated to seek out price information, exerts a potential effect on perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid. Additionally, financial literacy has a positive effect on actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. Consequently, contributors with low price consciousness and/or low financial literacy represent public policy target markets (e.g., for financial education programs, for specific regulations).

This study also shows that price based advertising exposure has an effect on perceived knowledge of commissions paid only. Therefore, the results suggest that pension fund providers could invest on building brand credibility in order to increase perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors. The findings of this study suggest that managers and regulators need to monitor brand credibility more closely. The results show that the effect of brand credibility does not depends on price consciousness or the use of the price-quality cue. That is, brand credibility could be effective across a wide range of contributors.

Implications for researchersThe current research shows the importance of investigating the perceived and actual knowledge of commission paid by contributors in the pension funds industry and offers some interesting explanations for why some contributors are more knowledgeable than others. Given that previous research on this topic is very limited, there are several avenues for future research, such as looking at other possible explanatory factors of the knowledge dimensions and comparing customer's perceived and actual price knowledge across financial services, customers and countries.

Further research is needed to extend these results beyond the pension funds industry. For example, an extension of price knowledge studies to mortgage loans, personal loans, mutual funds, insurances, etc. will be very useful, in order to determine what factors may affect price knowledge for financial services, and how the effects of these factors might vary between financial services.

Additionally, the role of firms and customer factors, other than those present in this study, on price knowledge remains open to further study. These possible factors could be brand positioning, brand loyalty, payment methods, the numerical price (e.g., prices that end in 9), the lifestyle of the customer, etc. In addition, future studies may include longitudinal and more comprehensive data (e.g., customer transaction histories), providing further insights on this issue.

Financial support from FONDECYT, under grant Iniciacion #11130614, is gratefully acknowledged. I thank reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have been very helpful to improve the paper.

Perceived knowledge of commission paid (adapted from Estelami, 2005)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (Rated on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 1=“strongly disagree” and 7=“strongly agree”).

My knowledge of commission paid in this type of service is quite good

I’m good at guessing commission paid of this type of service

I’m very confident in my estimates of commission paid in this type of service

Actual knowledge of commission paid (adapted from Dickson and Sawyer, 1990)

The stated commission paid is measured by, “What is the commission paid by contributors for ________ (brand of the pension fund provider)?”

The stated commission paid and the actual commission paid to the pension fund provider were recorded. The error between the latter two measures provides an estimate of the contestant's actual knowledge of commission paid. When the error is close to zero, it signifies an accurate estimate, close to the actual commission paid, and hence an accurate level of knowledge of commission paid by contributors. In contrast, when the error is large, contestant's knowledge of commission paid is likely to be poor.

Price consciousness (adapted from Batra and Sinha, 2000)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (Rated on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 1=“strongly disagree” and 7=“strongly agree”).

Commission paid is the most important factor when I am choosing a pension fund provider.

Use of the price-quality cue (adapted from Estelami and De Maeyer, 2004)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (Rated on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 1=“strongly disagree” and 7=“strongly agree”).

The higher the commission paid for this type of service, the higher the quality

Financial literacy (adapted from Van Rooij et al., 2011)

Questions measure the ability to perform simple calculations (in the first question), the understanding of how compound interest works (second question), and the effect of inflation (third question). Financial literacy is measured as the number of correct answers.

- 1.

Suppose you had 100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow? (More than 102, Exactly 102, Less than 102, do not know, Refusal)

- 2.

Suppose you had 100 in a savings account and the interest rate is 20% per year and you never withdraw money or interest payments. After 5 years, how much would you have on this account in total? (More than 200, Exactly 200, Less than 200, do not know, Refusal).

- 3.

Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, how much would you be able to buy with the money in this account? (More than today, exactly the same, less than today, do not know, Refusal).

Brand credibility (adapted from Kau and Loh, 2006)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (Rated on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 1=“strongly disagree” and 7=“strongly agree”).

I believe that _________ (brand of the pension fund provider) is trustworthy

Price based advertising exposure (adapted from Estelami and De Maeyer, 2004)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements? (Rated on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored by 1=“strongly disagree” and 7=“strongly agree”).

Commission paid for services like this are often advertised

Education level (adapted from Manzur et al., 2011)

What is your education level? (1=without education, 2=some primary school, 3=primary school, 4=some high school, 5=high school graduate, 6=some technical school, 7=technical school graduate, 8=some college, 9=college graduate, 10=post-graduate or more)

Age (Olavarrieta et al., 2012)

“What year were you born?”

Male

Gender (0=Female, 1=Male)

Brand customer (Olavarrieta et al., 2012)

Current customer of the pension fund provider (0=No, 1=Yes)

High-share brand (Manzur et al., 2012)

Brand share of the pension fund provider (0=Low-share brand, 1=High-share brand)