To assess the effectiveness of an educational intervention on antibiotic adherence and patient-reported resolution of symptoms.

DesignA controlled experimental study with systematic assignment to groups.

SettingA pharmacy in Murcia. Participants were patients who came to the pharmacy with a prescription for antibiotics. Intervention provided information on treatment characteristics (duration, dose and method of use) and correct compliance. A control group received routine care. Main variables “treatment adherence” and “perceived health” were evaluated one week after dispensation by telephone interview.

ResultsA total of 126 patients completed the study, 62 in the Control Group (CG) and 64 in the Intervention Group (IG). There were no differences between the groups in baseline characteristics, including the level of knowledge before the intervention. At the end of the study, treatment adherence in the CG was 48.4% (CI: 36.4–60.6), compared with 67.2% (CI: 55.0–77.4) in the IG. The difference of 18.8% was statistically significant (p=0.033; 95% CI=15.8–34.6). Non-compliance through missing more than one dose was 81.2% in the CG versus 38.1% in the IG, which is a statistically significant difference of 43.1% (p=0.001; 95% CI=16.4–63.1%). No significant differences were found in patient-perceived health. Logistic regression showed as predictor of adherence, the medication knowledge and the coincidence between duration of treatment indicated by physician and duration of treatment written in the prescription.

ConclusionsAn educational intervention during antibiotic dispensation improves treatment adherence versus routine care.

Evaluar la efectividad de la intervención educativa en la adherencia al tratamiento con antibióticos y en la evolución de los síntomas referidos por el paciente.

DiseñoEstudio experimental controlado con asignación sistemática. Emplazamiento: farmacia comunitaria en Murcia. Participantes: pacientes que acudieron a la farmacia con una receta de antibiótico.

IntervenciónAportar información sobre las características del tratamiento (duración, pauta y forma de utilización) y la correcta adherencia. En el grupo Control se procedió a una venta habitual. Mediciones principales: se evaluaron la «adherencia al tratamiento» y la «percepción de salud» a la semana de la dispensación mediante entrevista telefónica.

ResultadosFinalizaron el estudio 126pacientes: 62 en el Grupo Control (GC) y 64 en el Grupo Intervención (GI). No hubo diferencias entre grupos en las características basales, incluido el nivel de conocimientos previo a la intervención. Tras la intervención, la adherencia al tratamiento en el GC fue del 48,4% (IC 95%: 36,4-60,6) frente al 67,2% (IC 95%: 55,0-77,4) del GI, siendo esta diferencia del 18,8% (p=0,033; IC 95%: 15,8-34,6;). La falta de adherencia fue de más de una toma en el 81,2% GC vs el 38,1% GI, diferencia del 43,1% (p=0,001; IC 95%: 16,4-63,1%). En la percepción de salud del paciente no se encontraron diferencias. La regresión logística mostró como predictor de adherencia el conocimiento de la medicación y la coincidencia entre la duración del tratamiento indicado por el médico y la duración del envase prescrito en la receta.

ConclusionesUna intervención educativa durante la dispensación del antibiótico mejora la adherencia al tratamiento frente a una atención habitual.

Lack of treatment adherence and self-medication are two of the biggest problems in antibiotic misuse among patients.1–3 Adherence has been specially studied in chronic but not in acute diseases such as infectious diseases.4 A meta-analysis found that 37.8% of patients forget to take a dose of antibiotic.5 The rate of adherence in this therapy in our country is not well known. Few studies have examined the compliance with antibiotic regimens, with figures between 40 and 60%.6,7 The 42% found in the Pan European Survey of Patients was higher than values found in Italy (34%), Belgium (18%), France (16%) and Britain (9%).8

Unlike drugs that only affect individual patients, misused antibiotics add the global risk of bacterial resistance, which jeopardizes their effectiveness.9 In Spain resistance rates are particularly high and their consequences are serious: resistant bacterial infections are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, health demands, hospitalization, medical expense and impairment of the effectiveness of treatment of future patients.10,11

The WHO Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance encourages prescribers and dispensers to educate patients on the proper use of antibiotics and the importance of completing the prescribed treatment.12

Results of intervention studies in community pharmacy about improving treatment adherence are variable. A systematic revision conducted in 2005 concluded that it is impossible to identify an overall successful adherence-improving strategy performed by pharmacists and that more well-designed and well-conducted studies need to be performed.13

In our country there are few studies that address this question from the sphere of pharmacy; they are of local scope or with design problems, they provide written information and their results are non-significant.14,15 For this reason, we considered it important to conduct a study to evaluate the benefit of an oral educational intervention, in terms of increased treatment adherence and symptom improvement or resolution, vs. “routine pharmaceutical care”.

MethodsStudy populationOur study, the ICAB (Interventión in Compliance of AntiBiotics), is a community pharmacy-based, open-label, controlled trial to improve medication adherence in antibiotic users. The fieldwork took place at a community pharmacy in Murcia, and it covered a period of eight months (January–August 2010).

The study had an experimental design with a control group (CG), which followed routine dispensing practice, and an intervention group (IG), which followed an antibiotic dispensing protocol, as described below.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or older and came to the pharmacy during the study period to collect oral antibiotics prescribed for themselves or someone they were looking after.

Study designAll adult patients who came to the pharmacy with a prescription for an antibiotic were selected until the required sample size was attained. The patients were invited to sign the consent form and only those who gave their consent entered the study.

Assignment to groups was carried out systematically.We randomized if the first patient entered the intervention group or control group through a coin toss, and thereafter patients were assigned consecutively to the IG or the CG.

InterventionsThe patients or carers in the IG followed an antibiotic dispensing protocol drawn up by the head pharmacist. For this, a Dispensing Guideline that contained the most important pharmacological data on each antibiotic, using two books for reference,16,17 was written. The intervention focused on providing individualized verbal information to the patient or carer about treatment characteristics, duration, dosage regime and how to use the antibiotic. Written information was not provided. The talk took place in an area set apart from the counter, and lasted about 20min.

The subject's degree of knowledge of the antibiotic was evaluated before the intervention by means of the validated questionnaire by Garcia et al.18

If the antibiotic was being dispensed for the first time, the pharmacist checked if there were criteria for not dispensing it (clinically relevant interactions or contraindications, in which case the patient was referred to the physician), and the patient understood the process of using the antibiotic, through a knowledge test. If it was not the first time, treatment effectiveness was assessed, checking whether the antibiotic was being used correctly and safely through the same knowledge test. In all cases, if a lack of knowledge was detected, personalized information was provided to make up for it.

In the CG, any questions asked by the patient or carer at their initiative was answered, and the antibiotic was not dispensed if there were any criteria for not doing so.

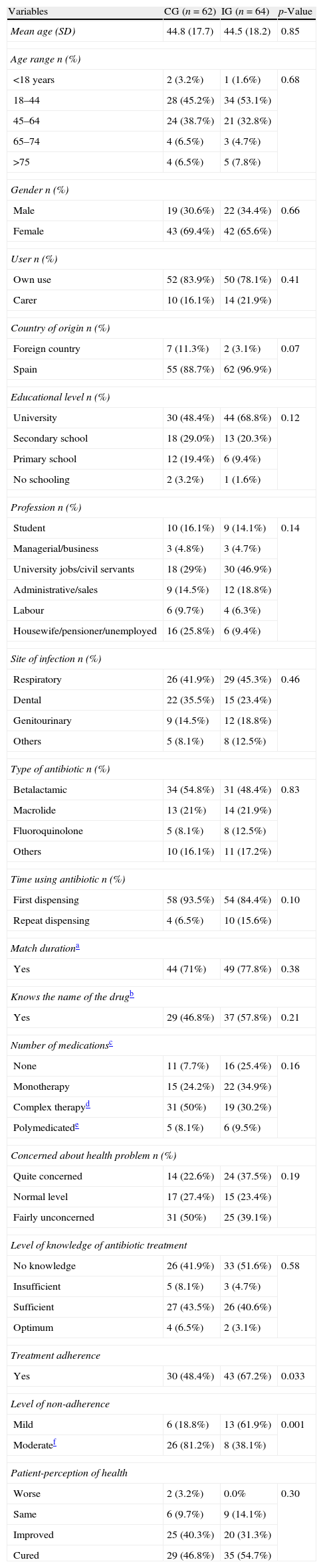

VariablesSociodemographic and clinical variables were registered in all cases (Table 1). We measured the coincidence between duration of treatment indicated by physician orally and duration of drugs container written in the prescription.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical variables between control group and intervention group.

| Variables | CG (n=62) | IG (n=64) | p-Value |

| Mean age (SD) | 44.8 (17.7) | 44.5 (18.2) | 0.85 |

| Age range n (%) | |||

| <18 years | 2 (3.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0.68 |

| 18–44 | 28 (45.2%) | 34 (53.1%) | |

| 45–64 | 24 (38.7%) | 21 (32.8%) | |

| 65–74 | 4 (6.5%) | 3 (4.7%) | |

| >75 | 4 (6.5%) | 5 (7.8%) | |

| Gender n (%) | |||

| Male | 19 (30.6%) | 22 (34.4%) | 0.66 |

| Female | 43 (69.4%) | 42 (65.6%) | |

| User n (%) | |||

| Own use | 52 (83.9%) | 50 (78.1%) | 0.41 |

| Carer | 10 (16.1%) | 14 (21.9%) | |

| Country of origin n (%) | |||

| Foreign country | 7 (11.3%) | 2 (3.1%) | 0.07 |

| Spain | 55 (88.7%) | 62 (96.9%) | |

| Educational level n (%) | |||

| University | 30 (48.4%) | 44 (68.8%) | 0.12 |

| Secondary school | 18 (29.0%) | 13 (20.3%) | |

| Primary school | 12 (19.4%) | 6 (9.4%) | |

| No schooling | 2 (3.2%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Profession n (%) | |||

| Student | 10 (16.1%) | 9 (14.1%) | 0.14 |

| Managerial/business | 3 (4.8%) | 3 (4.7%) | |

| University jobs/civil servants | 18 (29%) | 30 (46.9%) | |

| Administrative/sales | 9 (14.5%) | 12 (18.8%) | |

| Labour | 6 (9.7%) | 4 (6.3%) | |

| Housewife/pensioner/unemployed | 16 (25.8%) | 6 (9.4%) | |

| Site of infection n (%) | |||

| Respiratory | 26 (41.9%) | 29 (45.3%) | 0.46 |

| Dental | 22 (35.5%) | 15 (23.4%) | |

| Genitourinary | 9 (14.5%) | 12 (18.8%) | |

| Others | 5 (8.1%) | 8 (12.5%) | |

| Type of antibiotic n (%) | |||

| Betalactamic | 34 (54.8%) | 31 (48.4%) | 0.83 |

| Macrolide | 13 (21%) | 14 (21.9%) | |

| Fluoroquinolone | 5 (8.1%) | 8 (12.5%) | |

| Others | 10 (16.1%) | 11 (17.2%) | |

| Time using antibiotic n (%) | |||

| First dispensing | 58 (93.5%) | 54 (84.4%) | 0.10 |

| Repeat dispensing | 4 (6.5%) | 10 (15.6%) | |

| Match durationa | |||

| Yes | 44 (71%) | 49 (77.8%) | 0.38 |

| Knows the name of the drugb | |||

| Yes | 29 (46.8%) | 37 (57.8%) | 0.21 |

| Number of medicationsc | |||

| None | 11 (7.7%) | 16 (25.4%) | 0.16 |

| Monotherapy | 15 (24.2%) | 22 (34.9%) | |

| Complex therapyd | 31 (50%) | 19 (30.2%) | |

| Polymedicatede | 5 (8.1%) | 6 (9.5%) | |

| Concerned about health problem n (%) | |||

| Quite concerned | 14 (22.6%) | 24 (37.5%) | 0.19 |

| Normal level | 17 (27.4%) | 15 (23.4%) | |

| Fairly unconcerned | 31 (50%) | 25 (39.1%) | |

| Level of knowledge of antibiotic treatment | |||

| No knowledge | 26 (41.9%) | 33 (51.6%) | 0.58 |

| Insufficient | 5 (8.1%) | 3 (4.7%) | |

| Sufficient | 27 (43.5%) | 26 (40.6%) | |

| Optimum | 4 (6.5%) | 2 (3.1%) | |

| Treatment adherence | |||

| Yes | 30 (48.4%) | 43 (67.2%) | 0.033 |

| Level of non-adherence | |||

| Mild | 6 (18.8%) | 13 (61.9%) | 0.001 |

| Moderatef | 26 (81.2%) | 8 (38.1%) | |

| Patient-perception of health | |||

| Worse | 2 (3.2%) | 0.0% | 0.30 |

| Same | 6 (9.7%) | 9 (14.1%) | |

| Improved | 25 (40.3%) | 20 (31.3%) | |

| Cured | 29 (46.8%) | 35 (54.7%) | |

SD, standard deviation.

To determine the effectiveness of the intervention, a telephone interview was carried out seven days after the dispensation. In case of longer duration treatments, the call was delayed until the end date of treatment. The interviewer was blinded to the group allocation of the patient.

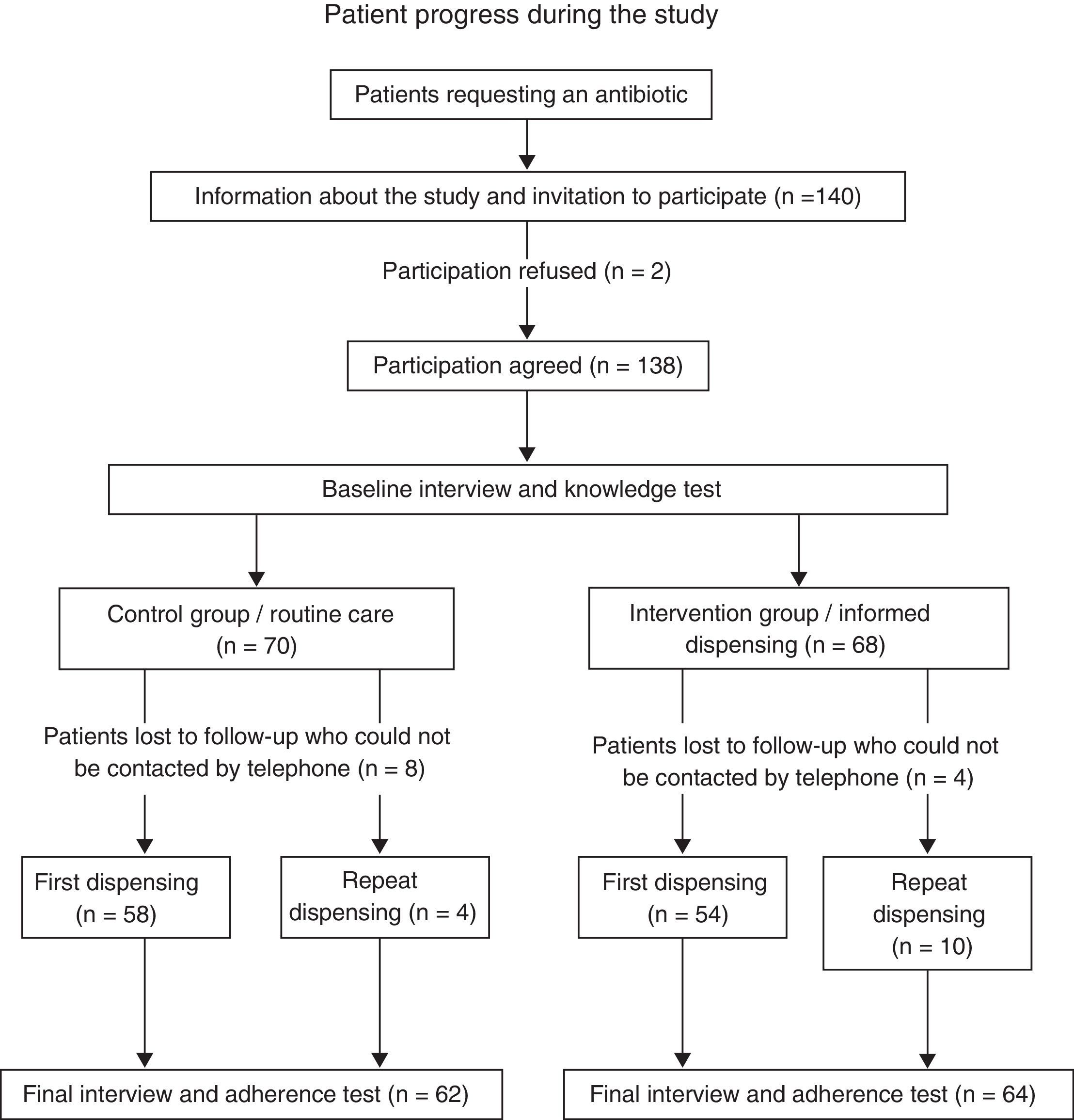

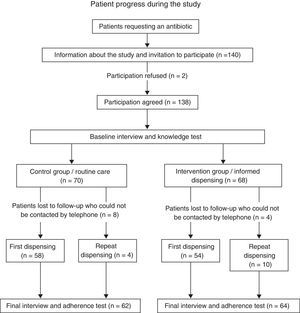

The study architecture is summarized in the flowchart.

The adherence to antibiotic treatment was evaluated by a combination of the Morisky–Green test and a self-reported Pill Count.19,20 Patients were considered compliant if they were categorized as such in both evaluations, and non-compliant if they were found to be non-compliant in either of the two tests. Patients who took liquid dosage forms were only evaluated using the Morisky–Green test.

Non-treatment-compliant patients were categorized as mild if a single dose was missed, and moderate, if more than one dose was missed.

The subject-perceived health was evaluated by the question: How did you get on with the treatment? The answers were classified as cured, improved, the same, or worse.

Statistical analysisThe required sample size was calculated in order to make a comparison of two proportions in independent groups, with an 80% power to detect a difference of 25% in adherence, assuming a compliance of 50% in the CG,26 using a two-tailed statistical test and an alpha risk of 0.05. At least 58 patients were required per group. Considering a potential loss to follow-up and dropout rate of 20%, 70 patients were needed to be enrolled in each group.

The statistical package SPSS v.18.0 was used for the data analysis. Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation (SD). Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated at 95%. The Pearson Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables.

To assess potential factors associated with treatment adherence, a binary logistic regression model was drawn up using the backward stepwise method (likelihood ratio).

The logistic regression model was used to analyze the association of the dichotomous dependent variable (adherence to antibiotic treatment) and a set of independent variables. The model included as predictors variables that were statistically significant in the bivariate analysis (p<0.1).

ResultsOf the 138 patients initially included, 12 were lost to follow-up because they could not be contacted by telephone. There were no statistically significant differences, so the 126 valid cases (62 CG vs. 64 IG) were analyzed.

The groups were comparable by the sociodemographic and clinical variables (Table 1). In the CG, the mean age was 44.8 years (SD=17.7) and in the IG it was 44.5 years (SD=18.2). There was a majority of women in both groups (69.4% and 65.6% in the CG and IG, respectively). No significant differences in the degree of knowledge were found between the groups.

Adherence to antibiotic treatment was 48.4% (CI: 36.4–60.6) in the CG and 67.2% (CI: 55.0–77.4) in the IG, with a difference of 18.8% (95% CI=15.8–34.6; p=0.033). Moderate non-compliance (more than one dose intake missing) was observed in 81.2% of patients in the CG and in 38.1% in the IG, with a difference of 43.1% (95% CI=16.4–63.1%; p=0.001).

There was no significant difference in the health perception, although it was higher in the IG, with reports of being “totally cured” in 54.7% (95% IC=42.6–66.3) in the IG and in 46.8% (95% IC=34.9–59.0) in the CG (p=0.297).

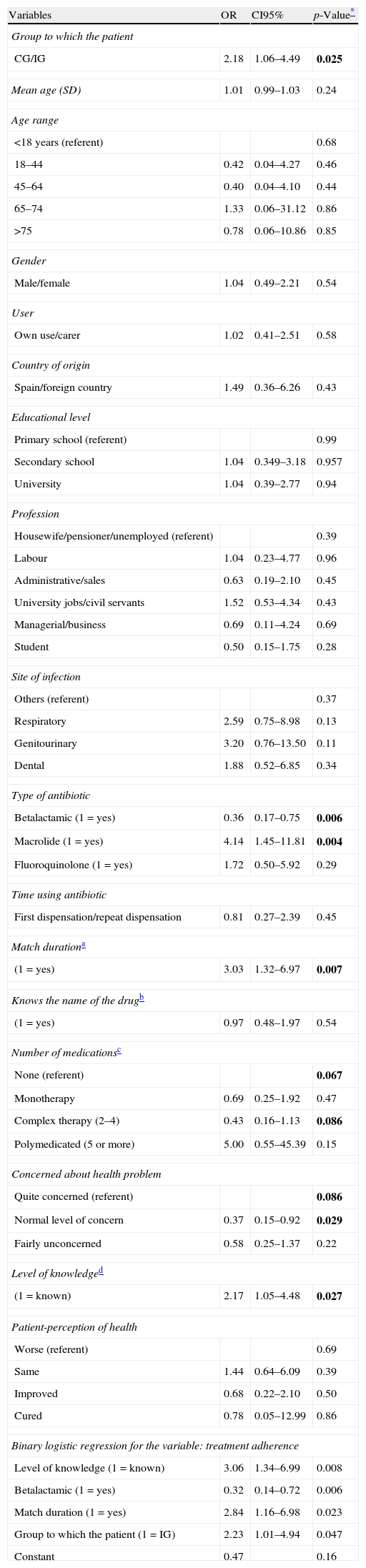

Results of the bivariate analysis are presented in Table 2. Variables with a p<0.1 were selected to be included in the regression model. The logistic regression analysis confirmed a group effect (OR 2.23; 95% CI=1.01–4.93; p=0.047). The variables that positively influenced adherence were the knowledge of the antibiotic treatment before the intervention (OR 3.06; 95% CI=1.34–6.99) and coincidence between duration of treatment indicated by physician and duration of drugs container written in the prescription (OR 2.84; 95% CI=1.16–6.99). The use of beta-lactams has a negative influence (OR 0.32; 95% CI=0.14–0.72). This model used 99.2% of the study sample. The model goodness-of-fit was good as assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (χ2 4.7; p=0.786).

Bivariate analysis of individuals with good adherence and binary logistic regression for the variable: treatment adherence.

| Variables | OR | CI95% | p-Value* |

| Group to which the patient | |||

| CG/IG | 2.18 | 1.06–4.49 | 0.025 |

| Mean age (SD) | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.24 |

| Age range | |||

| <18 years (referent) | 0.68 | ||

| 18–44 | 0.42 | 0.04–4.27 | 0.46 |

| 45–64 | 0.40 | 0.04–4.10 | 0.44 |

| 65–74 | 1.33 | 0.06–31.12 | 0.86 |

| >75 | 0.78 | 0.06–10.86 | 0.85 |

| Gender | |||

| Male/female | 1.04 | 0.49–2.21 | 0.54 |

| User | |||

| Own use/carer | 1.02 | 0.41–2.51 | 0.58 |

| Country of origin | |||

| Spain/foreign country | 1.49 | 0.36–6.26 | 0.43 |

| Educational level | |||

| Primary school (referent) | 0.99 | ||

| Secondary school | 1.04 | 0.349–3.18 | 0.957 |

| University | 1.04 | 0.39–2.77 | 0.94 |

| Profession | |||

| Housewife/pensioner/unemployed (referent) | 0.39 | ||

| Labour | 1.04 | 0.23–4.77 | 0.96 |

| Administrative/sales | 0.63 | 0.19–2.10 | 0.45 |

| University jobs/civil servants | 1.52 | 0.53–4.34 | 0.43 |

| Managerial/business | 0.69 | 0.11–4.24 | 0.69 |

| Student | 0.50 | 0.15–1.75 | 0.28 |

| Site of infection | |||

| Others (referent) | 0.37 | ||

| Respiratory | 2.59 | 0.75–8.98 | 0.13 |

| Genitourinary | 3.20 | 0.76–13.50 | 0.11 |

| Dental | 1.88 | 0.52–6.85 | 0.34 |

| Type of antibiotic | |||

| Betalactamic (1=yes) | 0.36 | 0.17–0.75 | 0.006 |

| Macrolide (1=yes) | 4.14 | 1.45–11.81 | 0.004 |

| Fluoroquinolone (1=yes) | 1.72 | 0.50–5.92 | 0.29 |

| Time using antibiotic | |||

| First dispensation/repeat dispensation | 0.81 | 0.27–2.39 | 0.45 |

| Match durationa | |||

| (1=yes) | 3.03 | 1.32–6.97 | 0.007 |

| Knows the name of the drugb | |||

| (1=yes) | 0.97 | 0.48–1.97 | 0.54 |

| Number of medicationsc | |||

| None (referent) | 0.067 | ||

| Monotherapy | 0.69 | 0.25–1.92 | 0.47 |

| Complex therapy (2–4) | 0.43 | 0.16–1.13 | 0.086 |

| Polymedicated (5 or more) | 5.00 | 0.55–45.39 | 0.15 |

| Concerned about health problem | |||

| Quite concerned (referent) | 0.086 | ||

| Normal level of concern | 0.37 | 0.15–0.92 | 0.029 |

| Fairly unconcerned | 0.58 | 0.25–1.37 | 0.22 |

| Level of knowledged | |||

| (1=known) | 2.17 | 1.05–4.48 | 0.027 |

| Patient-perception of health | |||

| Worse (referent) | 0.69 | ||

| Same | 1.44 | 0.64–6.09 | 0.39 |

| Improved | 0.68 | 0.22–2.10 | 0.50 |

| Cured | 0.78 | 0.05–12.99 | 0.86 |

| Binary logistic regression for the variable: treatment adherence | |||

| Level of knowledge (1=known) | 3.06 | 1.34–6.99 | 0.008 |

| Betalactamic (1=yes) | 0.32 | 0.14–0.72 | 0.006 |

| Match duration (1=yes) | 2.84 | 1.16–6.98 | 0.023 |

| Group to which the patient (1=IG) | 2.23 | 1.01–4.94 | 0.047 |

| Constant | 0.47 | 0.16 | |

CI, confidence interval.

The study results show that implementing an educational intervention when patients come to a pharmacy to collect antibiotics that they have been prescribed, increases adherence to the treatment. However, this does not mean that the patient will feel cured at the end of the treatment course. The educational intervention in this study was effective, with an 18.8% difference in compliance between the CG and the IG.

A meta-analysis and a Cochrane review found interventions carried out by health professionals (physicians, nurses, pharmacists) to be effective on treatment adherence,21,22 but pharmaceutical interventions found mixed results13,23–25 and it is difficult to identify an overall successful strategy improving adherence – performed by pharmacists. In our country, there have been positive results following the intervention of hospital pharmacists in patients with other pathologies, albeit with a small sample size26. In a community pharmacy, Machuca et al. achieved a 14% increase in the antibiotics adherence.14 Andres et al. also improved adherence, although the differences were not statistically significant.15 The intervention in these studies was done with written information, and their results were not strong. The results of our study provide valuable information about the effectiveness of oral interventions on the treatment adherence in the community pharmacies, which are close and accessible to the patient, and should be used to actively work with other health professionals in the appropriate use of antibiotics.

The adherence in the IG was higher than average antibiotic therapy adherence reported in Spain by Gil et al., although it is very similar to that found by other authors.6,19 This difference may be related to the measuring method, as Gil et al. used the technique of pill counts, while the other two used the telephone interview. Factors that were not evaluated and that can influence adherence are the duration of the treatments and the level of education of the study population.

Our results are lower than those found in a meta-analysis conducted internationally,5 and the difference may be related to the high rate of resistance in our country.8 It is difficult to maintain the effectiveness of adherence interventions over time, and this can explain the better results in acute diseases.

No significant differences were found between groups with regard to patient-perceived health. This may be due to the fact that the infectious process is self-limiting in most cases and resolves without intervention in a short time. Different studies show that there is a relationship between health as perceived by patients and their adherence to treatment.19,27 It therefore seems important to analyze this variable. However, we must bear in mind that we measured the perceived health through a single direct question to the patient, so the results need to be interpreted with caution.

Patients frequently report discontinuing antibiotic therapy when they begin to feel better or when adverse events occur.28 This might be the main cause of the existence of antibiotics at home29 and of self-medication, in few cases responsible for the emergence of resistance.8,29

Logistic regression showed an association between adherence and the coincidence between the duration of treatment orally indicated by the physician and the duration of treatment written on the prescription. The mismatch between the duration of antibiotic treatment and the format in which drugs are manufactured sometimes makes more than one container necessary, and therefore more than one prescription to end the treatment. This could be a barrier for patients to successfully complete their treatment. In August 2012, the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products issued a Resolution on matching therapeutic drug formats (J01 and J02 group), urging manufacturers to adapt to proper formats for these treatments.30

Logistic regression also showed that medication knowledge is correlated with medication adherence. This finding is according to a recent publication.31 Therefore improvement in the patient's knowledge would bear a positive effect on adherence, and patient education in the proposed dispensing protocol is considered to be an implicit strategy for improving compliance. Pharmacists should be encouraged to play a proactive role in large-scale health education programmes.

We evaluated patients’ baseline knowledge with a validated questionnaire – this is a strong point of our study, as it is the first validated questionnaire to specifically assess knowledge of patient medication.20

The study has the limitations inherent to using different indirect tests, which tend to overestimate adherence, although the use of two different methods can reduce the bias. A contamination effect could have occurred considering that both groups have antibiotics dispensed from the same site, and the intervention effect could have been increased. The study was conducted in a local setting, so the results cannot be extrapolated to wider settings. The patient allocation was not randomized, and this can be a design of weakness. For future studies it would be advisable to use a randomized clinical trial design, in order to eliminate this possible bias.

In conclusion, pharmaceutical intervention increased antibiotic adherence in this community pharmacy. The results suggest that knowledge is an important factor associated to adherence, and that an intervention aimed at increasing it may improve adherence. Thereby, this report also reinforces the pharmacists’ role in improving the health care system and they should be strengthened as educators in the rational use of medicines. It is necessary to conduct multicenter studies to support this thesis, to verify that the implementation of these services in the pharmacy is, not only effective, but also feasible and compatible with the rest of the activities.

- •

Lack of treatment adherence and self-medication are two of the biggest problems in antibiotic misuse among patients.

- •

The rate of adherence in antibiotic therapy in our country is not well known.

- •

Intervention studies in community pharmacy about improving adherence to treatment have obtained different results.

- •

The research results indicate that the contribution of personalized information orally during the dispensing could increase adherence to treatment.

- •

Pharmacists can improve adherence to treatment with antibiotics, so it will be more effective treatments and could limit the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

- •

The community pharmacy is a healthcare area close and accessible to the patient, and should be exploited to actively work with other health professionals in the appropriate use of antibiotics.