Whether the guidelines on infant nutrition, food allergy and atopic dermatitis confer real health benefits in practice at the population level has not been deeply studied. We aimed here to characterize the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding these issues among primary health care professionals. In addition, we surveyed available parent-reported information sources and the incidence of food-related symptoms, dietary restrictions, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis among one-year-old children in the general population.

Materials and methodsAn online questionnaire was designed for public health nurses and general practitioners. In addition, parents of one-year-old children were recruited to a separate survey at the time of their regular check-up visit.

ResultsAltogether, 80 professionals took part. The median overall knowledge score was 77% and significantly higher among the general practitioners than among the nurses (p=0.004). However, only 35% of all the professionals recognized either severe airway or cardiovascular symptoms as potential food allergy-related symptoms. Moisturizers and emollients were thought to be adequate treatment for atopic dermatitis by 56%. Among 248 one-year-old children, the incidence of food allergy was 4% and atopic dermatitis 13%. During this period, parents intentionally avoided giving at least one food to 23% of the children, yet more than 80% of these restrictions can be regarded as unnecessary.

ConclusionThe knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding infant feeding, food allergy, and atopic dermatitis varied significantly among the primary care professionals. This will likely result in heterogeneous guidance practices and confusion among the families at the population level.

The reported incidence of doctor-diagnosed food allergy (FA) is 1–6% among children in the U.S. and Europe.1,2 However, up to 30% of parents report their child as having this condition.3 Furthermore, as many as 50% of families intentionally exclude various foods from a child's diet.4 This discrepancy may reflect difficulties in interpreting the symptoms and a lack of adequate information provided by health care professionals.

Over the past several decades, infant feeding guidelines have changed more than once,5 and a plethora of ever-changing clinical care guidelines, expert opinion statements, booklets, and online material regarding FA and atopic dermatitis (AD) has been produced for both health care professionals and the public during the same period. This thicket of information has the potential to foment confusion and heterogeneous guidance practices.

Different countries have different occupational groups that provide frontline guidance to families. They include nutritionists, nurses, nurse practitioners, general practitioners, and pediatricians. In Finland, the public health nurses (PHNs) work independently, in collaboration with primary care physicians.6 PHNs provide the primary information to families regarding feeding practices, and are usually the first to be contacted in cases of food-related symptoms and eczema. They also decide whether there is a need to arrange an extra consultation or referral to a doctor. The primary goal of the present survey was to characterize knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions concerning infant feeding practices, FA, and AD among PHNs and general practitioners (GPs). In addition, we carried out a small survey on the parents’ information sources and the incidence of food-related symptoms, dietary restrictions, FA, and AD among one-year-old children in the general population.

MethodsThe design of the survey for health care professionalsA questionnaire was designed to characterize knowledge, attitudes and perceptions concerning infant feeding practices, FA and AD among primary care health nurses and general practitioners. The questions were created on the basis of the national Finnish guidelines.7 The questionnaire consisted of 94 items, of which 68 questions related to FA and AD (65 true/false items, two multiple-choice items and one item on the recognition of 18 various FA symptoms), and six to infant feeding recommendations (two true/false items and four multiple-choice items). See Supplementary Table S1. The remaining 20 Likert scale questions assessed attitudes and perceptions. The survey also asked for work experience (years) and the sources of information regarding infant feeding, FA, and AD.

The questionnaire was first tested and evaluated by seven professionals (two experienced nurses, one senior allergist, and four pediatric trainees), and then modified according to their comments. The voluntary survey was carried out between December 16th, 2013 and February 28th, 2014. An information letter describing the study protocol and including a link to the online questionnaire (Webropol Ltd) was provided to all 91 PHNs and 60 GPs working in child health clinics in all primary health care centers in the city of Oulu. Fifty-eight (64%) PHNs and 22 (37%) doctors took part in the survey.

The design of the survey for the parents of one-year-old childrenParents with one-year-old children were recruited to a separate survey at the time of their regular check-up visit. The design of the questionnaire is shown in Supplementary Table S2. PHNs in all child health clinics in the city of Oulu delivered the questionnaire booklet to the parents (after obtaining informed consent) between August 15th, 2012 and August 31st, 2013. The parents were asked to fill out the questionnaire and mail it to the investigators in an attached prepaid envelope. Thirty-one percent of those asked (248 of 800) returned the questionnaire.

Statistical methodsSummary scores were created by calculating the percentage of knowledge items that each respondent answered correctly. Descriptive analyses included presentation of overall and subgroup scores, percentages of respondents who recognized each FA symptom item correctly, and scores according to respondent occupation (PHN and GP). Differences in the distribution of knowledge scores between the two occupational groups were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test. To describe the perceptions of the health care personnel, the response categories were collapsed to strongly disagree/disagree, neutral (neither agree nor disagree), and strongly agree/agree. The chi-square test was used to compare the frequencies between the category variables. The same statistical methods were used to analyze the data from the survey on one-year-old children. All the data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics Software for Windows Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

ResultsCharacteristics of the health care personnelAltogether, 80 health care professionals took part in the survey, of whom 72.5% were PHNs and 27.5% GPs. The median length of working experience was 11 years (range 0–30 years). Only 13% of doctors, compared to 83% of PHNs, were acquainted with the National Nutrition Recommendation (p<0.001). In contrast, 95% of doctors were acquainted with the Finnish Current Care Guideline on FA, and 95% with the Finnish Current Care Guideline on Atopic Eczema, compared to 47% (p<0.001) and 29% (p<0.001) of PHNs, respectively. Other current information sources (reported by 25 participants) on infant feeding and atopic diseases were The Handbook for Child Welfare Clinics (The Finnish version is at https://www.thl.fi/en/web/lastenneuvolakasikirja), various Internet sources, and various printed materials provided by The Finnish Allergy and Asthma Federation as well as by commercial companies.

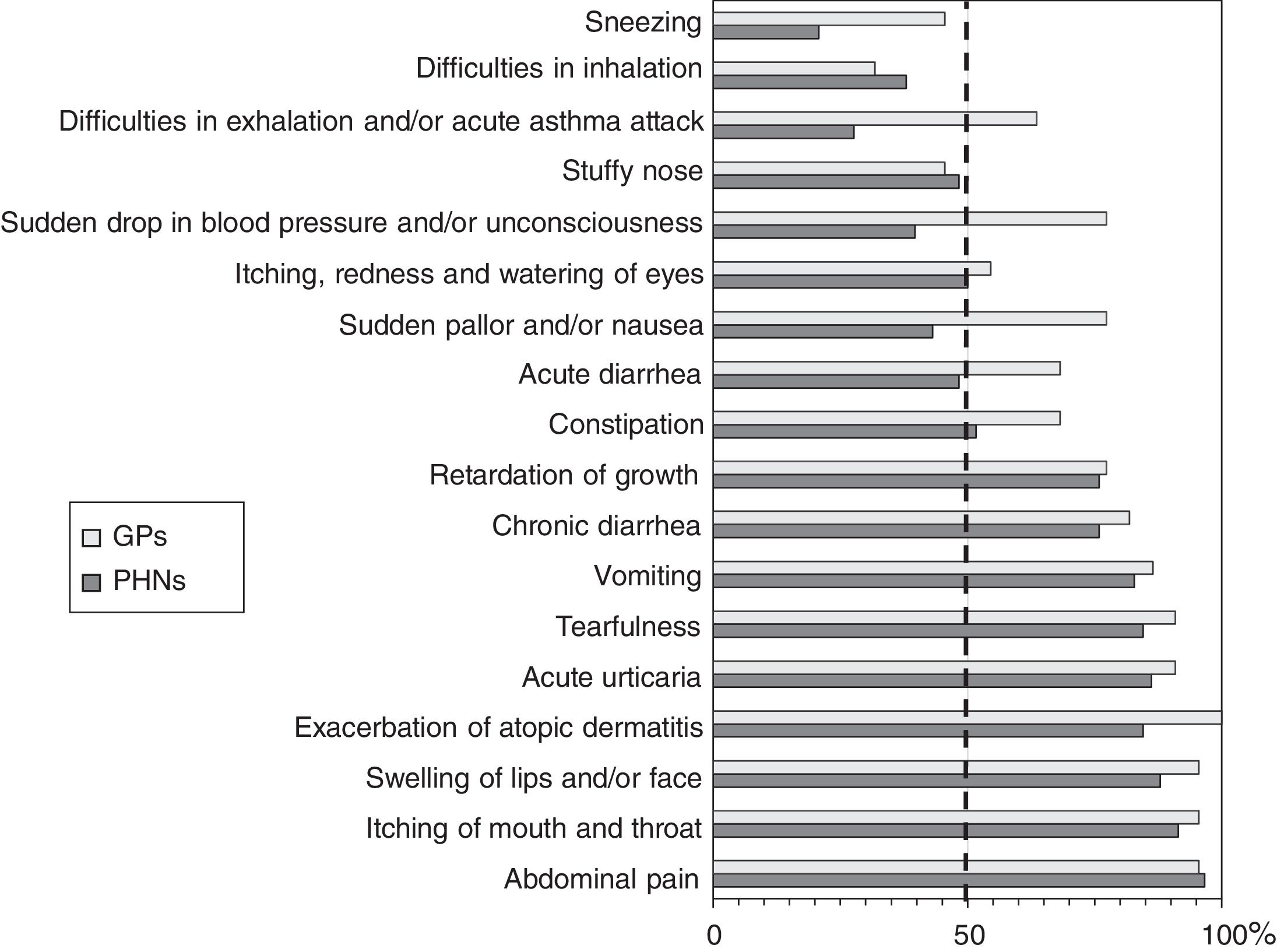

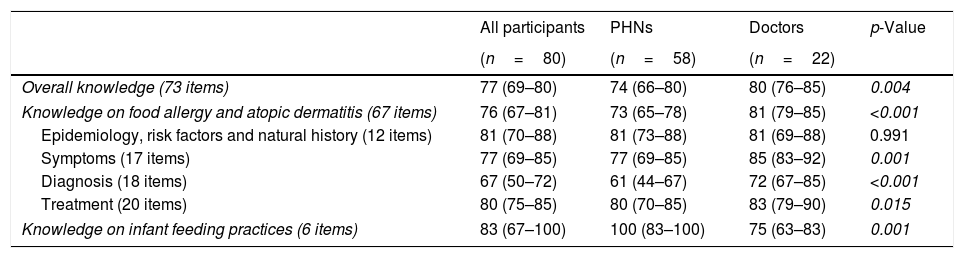

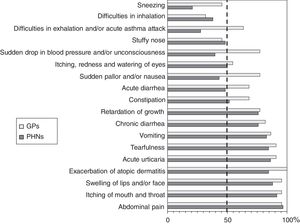

Knowledge on infant feeding practices, FA, and atopic eczemaThe summary scores of knowledge are presented in Table 1, and the results of the single-knowledge items appear in Supplementary Table S1. The median overall knowledge score was 77% and significantly higher among the GPs than among the PHNs (p=0.004). The results of the recognition of 18 specific FA-related symptoms are shown in Fig. 1. Most strikingly, only 14% of the PHNs and 18% of the GPs recognized inspiratory stridor and expiratory obstruction/acute asthma attack as potential symptoms of FA. Correspondingly, only 33% of the PHNs, as against 73% of the doctors (p=0.002), recognized sudden pallor/dysphoria and sudden drop in blood pressure/loss of consciousness as potential FA-related symptoms. Furthermore, conjunctival and nasal symptoms were very poorly recognized in both occupational groups.

Knowledge on infant feeding practices, food allergy and atopic dermatitis among primary care health professionals working in child health clinics.

| All participants | PHNs | Doctors | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=80) | (n=58) | (n=22) | ||

| Overall knowledge (73 items) | 77 (69–80) | 74 (66–80) | 80 (76–85) | 0.004 |

| Knowledge on food allergy and atopic dermatitis (67 items) | 76 (67–81) | 73 (65–78) | 81 (79–85) | <0.001 |

| Epidemiology, risk factors and natural history (12 items) | 81 (70–88) | 81 (73–88) | 81 (69–88) | 0.991 |

| Symptoms (17 items) | 77 (69–85) | 77 (69–85) | 85 (83–92) | 0.001 |

| Diagnosis (18 items) | 67 (50–72) | 61 (44–67) | 72 (67–85) | <0.001 |

| Treatment (20 items) | 80 (75–85) | 80 (70–85) | 83 (79–90) | 0.015 |

| Knowledge on infant feeding practices (6 items) | 83 (67–100) | 100 (83–100) | 75 (63–83) | 0.001 |

Data represent median (interquartile range) percentage of correctly answered questions in each question category. Statistical comparison (Mann–Whitney U test) was done between the two occupational groups. p-Value of 0.05 or less represent statistically significant difference and are shown in italics. PHNs, public health nurses.

The recognition of 18 specific food allergy related symptoms among primary health care professionals. The percentage represents professionals who correctly recognized that the symptom could potentially be caused by food allergy. The dashed line is set at 50% to demonstrate very poor knowledge of several key symptoms, as even flipping a coin (guessing) will give a chance of 50%. PHN=public health nurse.

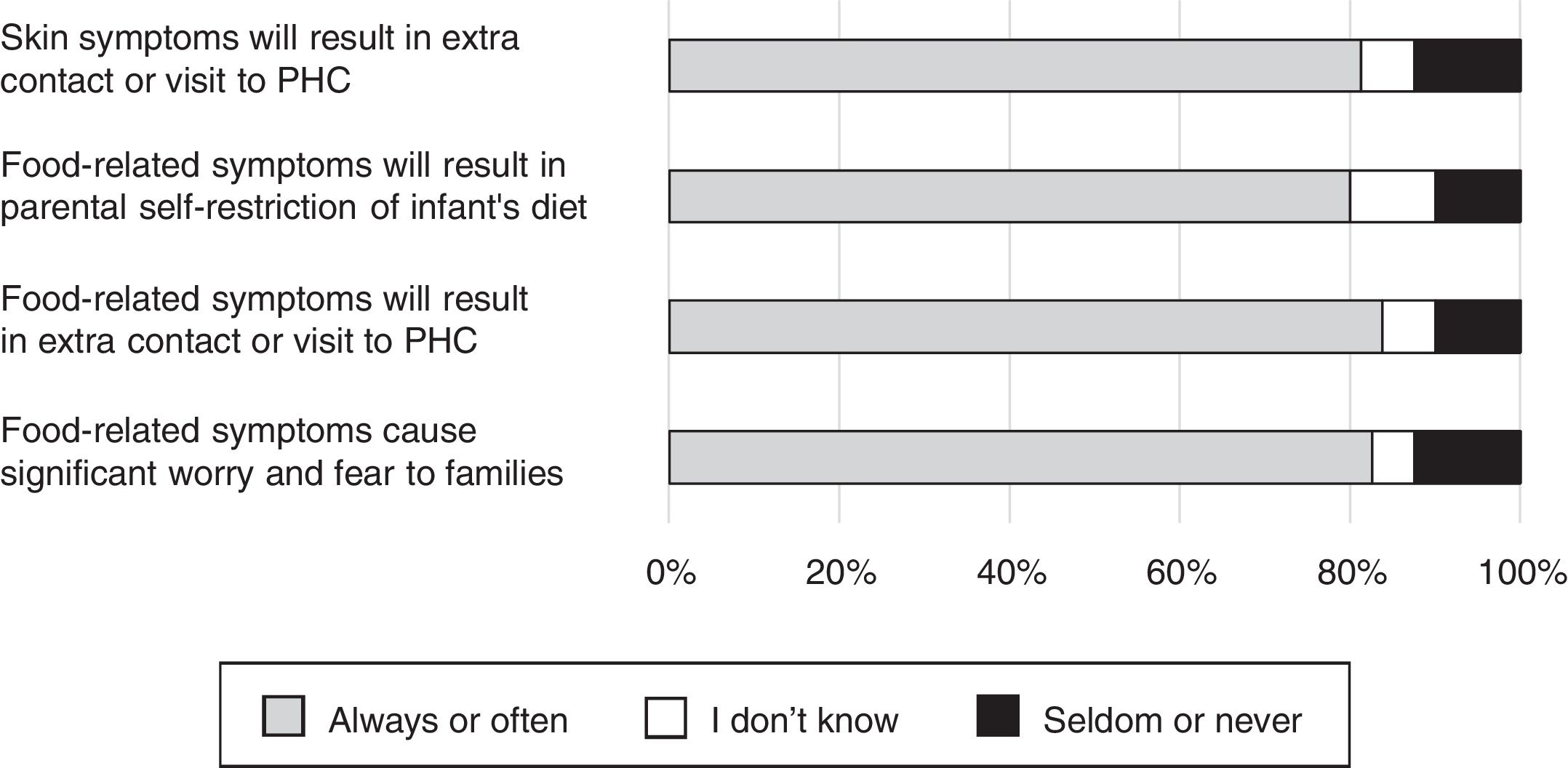

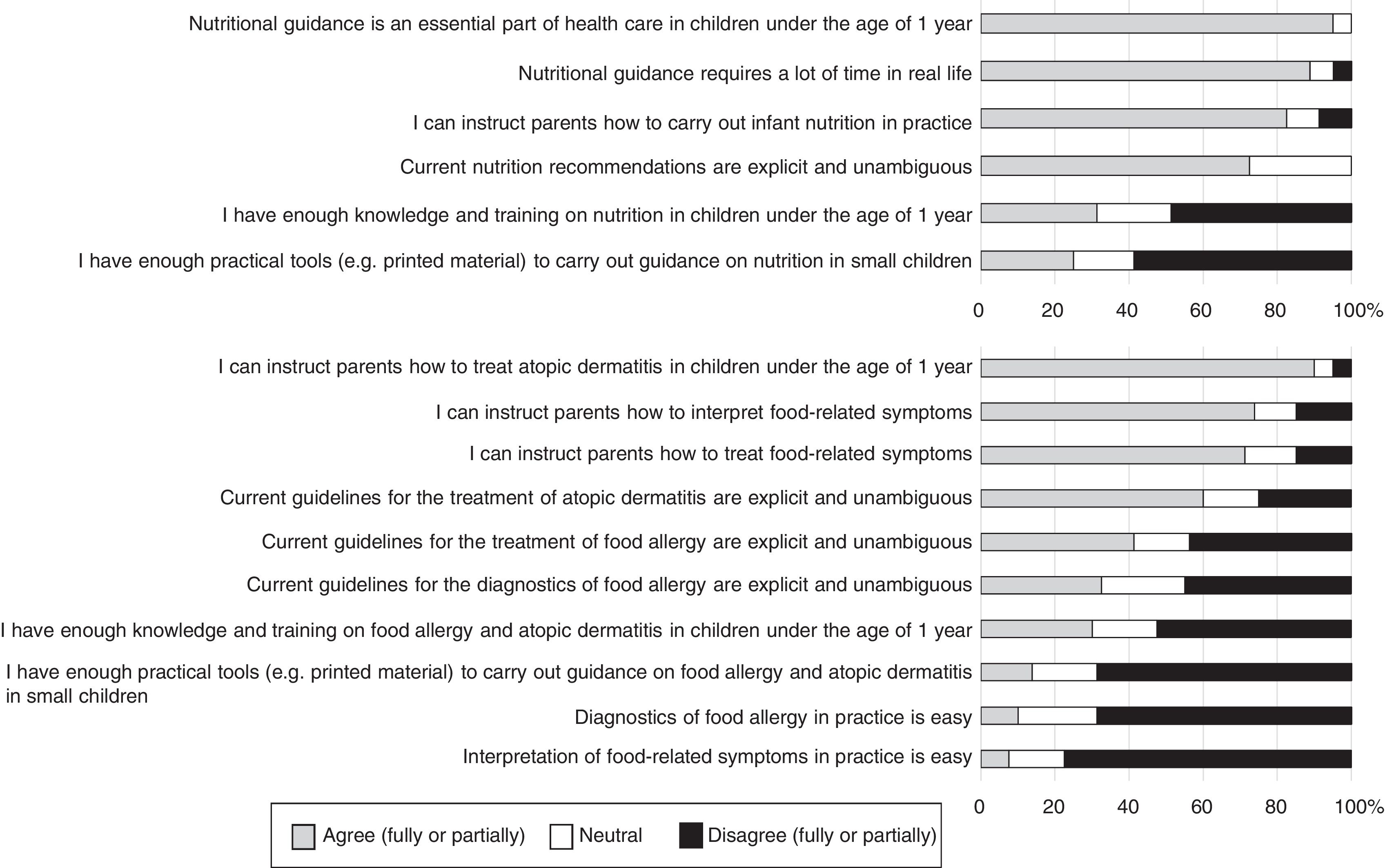

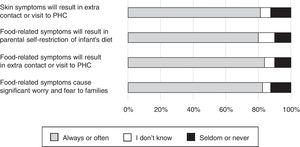

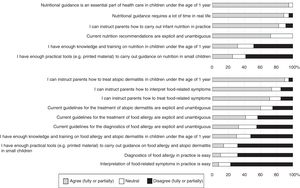

Attitudes and perceptions are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3. More than 80% of participants thought that food-related symptoms always or often cause significant anxiety and result in the introduction of an elimination diet. Eighty-four percent reported that potentially food-related symptoms or eczema in a child under one year of age had resulted in an extra call and 81% that they had resulted in a visit to health care. Most thought that they had the ability to instruct families on interpretation and treatment of food-related symptoms in a child, and more than 90% thought that they could tell parents how to treat AD in children in their first year of life, even though 56% falsely answered that moisturizers and emollients were adequate treatments for AD. However, 94% (100% of GPs and 92% of PHNs) knew that mild topical corticosteroids were approved for children under the age of one (see Supplementary Table S1).

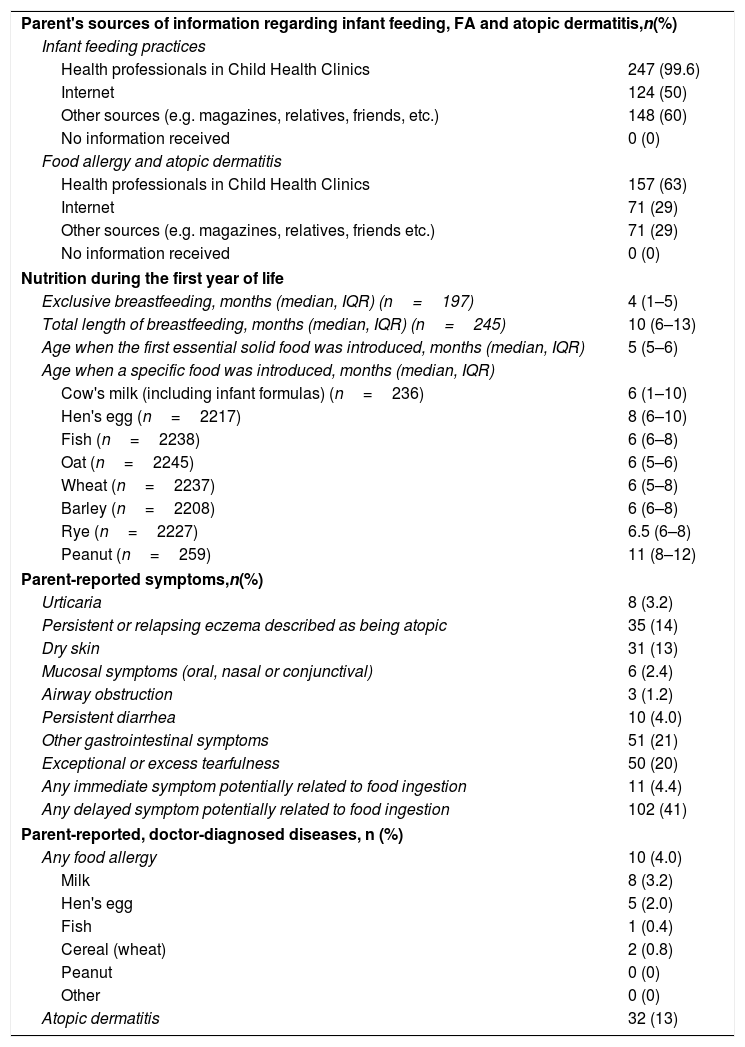

The major results of our survey on one-year-old children (n=248, of whom 119, or 48%, were boys) are presented in Table 2. The median length of exclusive breastfeeding was four months and overall breastfeeding 10 months. The median age of introduction of any solid food was five months, and, for the major potentially allergenic solid foods (egg, fish, oat, wheat, barley, rye, and peanut), the median age of introduction varied from six to 11 months. Furthermore, by the age of one year, 12 children (4.8%) had not yet been introduced to cow's milk, 31 (12.5%) to hen's egg, 10 (4.0%) to fish, three (1.2%) to oat, one (0.4%) to wheat, 40 (16.1%) to barley, 21 (8.5%) to rye, and as many as 189 (76.2%) to peanut.

A survey-based characteristics of parent's sources of information, infant nutrition practices, and the incidence of potential food related symptoms and atopic diseases among the 248 children by the age of 1 year.

| Parent's sources of information regarding infant feeding, FA and atopic dermatitis,n(%) | |

| Infant feeding practices | |

| Health professionals in Child Health Clinics | 247 (99.6) |

| Internet | 124 (50) |

| Other sources (e.g. magazines, relatives, friends, etc.) | 148 (60) |

| No information received | 0 (0) |

| Food allergy and atopic dermatitis | |

| Health professionals in Child Health Clinics | 157 (63) |

| Internet | 71 (29) |

| Other sources (e.g. magazines, relatives, friends etc.) | 71 (29) |

| No information received | 0 (0) |

| Nutrition during the first year of life | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding, months (median, IQR) (n=197) | 4 (1–5) |

| Total length of breastfeeding, months (median, IQR) (n=245) | 10 (6–13) |

| Age when the first essential solid food was introduced, months (median, IQR) | 5 (5–6) |

| Age when a specific food was introduced, months (median, IQR) | |

| Cow's milk (including infant formulas) (n=236) | 6 (1–10) |

| Hen's egg (n=2217) | 8 (6–10) |

| Fish (n=2238) | 6 (6–8) |

| Oat (n=2245) | 6 (5–6) |

| Wheat (n=2237) | 6 (5–8) |

| Barley (n=2208) | 6 (6–8) |

| Rye (n=2227) | 6.5 (6–8) |

| Peanut (n=259) | 11 (8–12) |

| Parent-reported symptoms,n(%) | |

| Urticaria | 8 (3.2) |

| Persistent or relapsing eczema described as being atopic | 35 (14) |

| Dry skin | 31 (13) |

| Mucosal symptoms (oral, nasal or conjunctival) | 6 (2.4) |

| Airway obstruction | 3 (1.2) |

| Persistent diarrhea | 10 (4.0) |

| Other gastrointestinal symptoms | 51 (21) |

| Exceptional or excess tearfulness | 50 (20) |

| Any immediate symptom potentially related to food ingestion | 11 (4.4) |

| Any delayed symptom potentially related to food ingestion | 102 (41) |

| Parent-reported, doctor-diagnosed diseases, n (%) | |

| Any food allergy | 10 (4.0) |

| Milk | 8 (3.2) |

| Hen's egg | 5 (2.0) |

| Fish | 1 (0.4) |

| Cereal (wheat) | 2 (0.8) |

| Peanut | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 32 (13) |

Immediate food-related symptoms were reported in 11 children (4.4%) and one or more food substances had intentionally been avoided in nine of these (Table 2). Delayed food-related symptoms (any food) were reported in 102 children (41%), including all those 11 children with immediate symptoms. Forty-three (43%) of them had intentionally avoided one or more food substances (9% among those without symptoms, p<0.001). The incidence of parent-reported, doctor-diagnosed FA (any food) by the age of one year was 4.0% (10 of 248).

There were 32 parent-reported, doctor-diagnosed cases of AD (13%) as shown in Table 2). In 12 of these (38%), one or more food substances were intentionally avoided during the first year of life (21% among those without doctor-diagnosed AD, p=0.035), and 88% had used topical corticosteroids for treatment. Surprisingly, topical corticosteroids had also been used in 11.4% (20 of 176) of children with neither diagnosis of AD nor any skin symptoms. Fifteen of these (75%) had received information about allergies and AD from the public child health clinics, eight (40%) from the internet and seven (35%) from other sources.

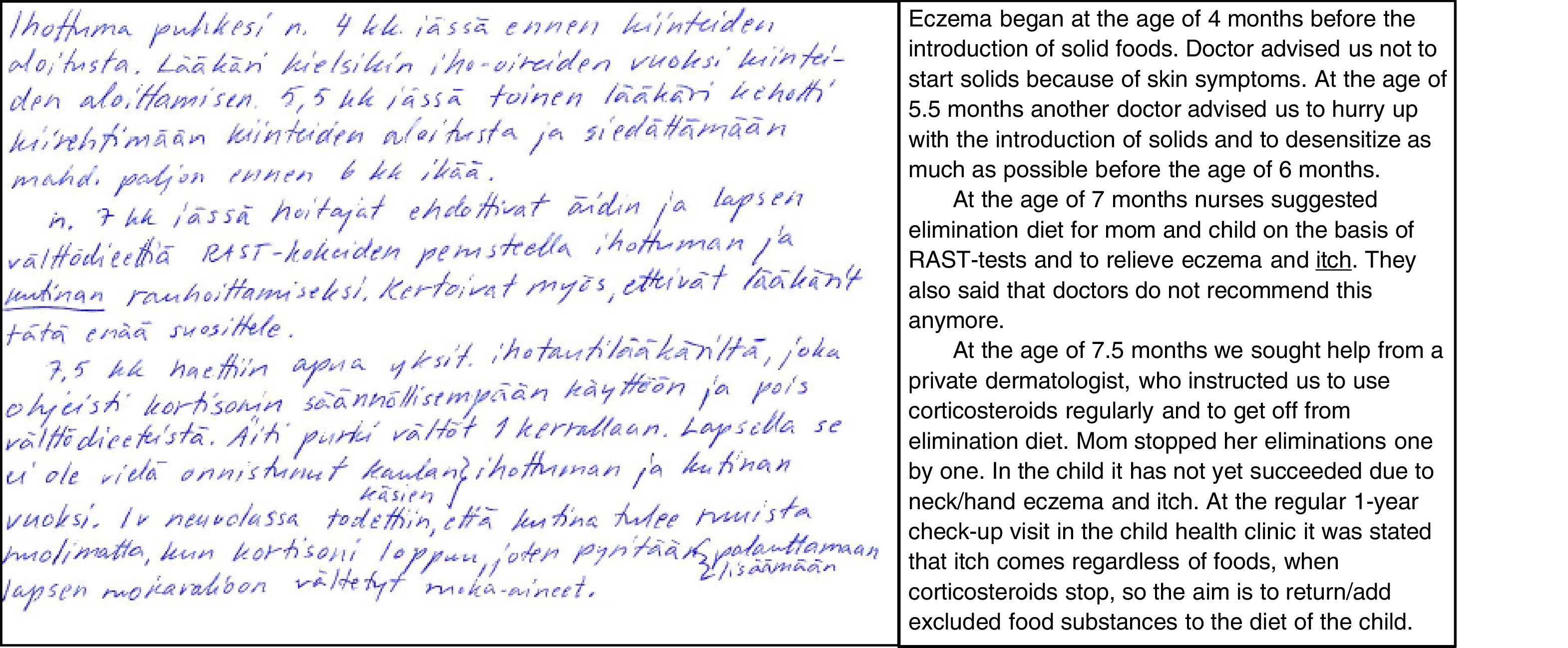

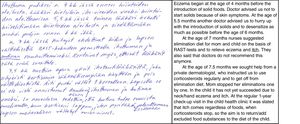

DiscussionInternational and national guidelines offer health care professionals the best available information to ensure optimal growth and development of the baby and to ensure evidence-based diagnostics and treatment of FA and AD in children. Whether these guidelines confer real health benefits in practice at the population level has not been deeply studied. Our results show high individual and occupational variability in acquaintance with the guidelines. Furthermore, both health care professionals and families use additional sources of information that are not consistent with each other. These habits, together with the changing nature of the guidelines, seem to result in contradictory information and remarkable confusion among the families, as one mother in our survey told us (illustrated in Fig. 4).

A parent's real-life description of parental confusion caused by discrepancies among health professionals’ provision of instructions regarding infant feeding, food allergy and atopic dermatitis in a child. L: a photo of the original Finnish handwritten free comment in the questionnaire booklet; R: free translation of the text into English.

There are very few published studies from any country into the knowledge and perceptions on childhood food allergies in primary care settings. All of these have reported passable or poor areas of knowledge. In the U.S. study, 61% of 407 primary care physicians answered FA-related knowledge-based items correctly.8 The authors concluded that the overall knowledge was fair but that significant knowledge gaps existed and needed to be addressed. In a Turkish study, knowledge of FA and anaphylaxis among primary care physicians was found to be unsatisfactory, as the average percentage of correct answers was only 47% among the 297 participants.9 An Australian survey that included GPs reported significant gaps and variability in knowledge of the diagnosis and management of FA, potentially resulting in clinical practices inconsistent with international guidelines.10 A Brazilian study of 300 physicians and 220 nutritionists revealed many gaps in their knowledge of primary FA prevention.11 Our present study is the first to focus on knowledge and perceptions among primary care professionals while taking three factors together—infant nutrition, AD and FA. The overall knowledge of 77% is somewhat better than reported in other studies, but is still unsatisfactory in several areas.

The study's most serious finding is that frontline health care professionals are poor at recognizing many significant symptoms of FA. Most importantly, only 14% of the PHNs and 18% of the GPs knew that severe airway symptoms can be caused by an allergic reaction to food. Correspondingly, only 33% of the PHNs, compared to 73% of the GPs, recognized severe cardiovascular symptoms as potentially FA-related. These gaps of knowledge are alarming, as they indicate that frontline professionals cannot teach parents to recognize the symptoms themselves. This may delay the treatment of acute allergic reactions.

Another remarkable observation is a clear discrepancy between professionals’ knowledge and the perceptions of their own skills regarding FA and AD in small children. A very large proportion thought that they knew how to instruct families in the diagnosis, interpretation, and treatment of food-related symptoms in a child, even though we observed clear knowledge gaps in these areas. Furthermore, the results of the survey into AD treatment knowledge are contradictory, as they show that roughly 90% of participants reported their ability to instruct families in the treatment of AD in children under the age of one, even though 56% answered that moisturizers and emollients were adequate treatments for the condition. On the other hand, the majority agreed on the difficulty of diagnosing and interpreting food-related symptoms, and believed that they did not have enough training and practical tools to instruct families in the treatment of AD and food allergies.

Nearly all the frontline public health care professionals in our study recognized guidance on nutrition as an essential, although time-consuming, part of infant health care. Eighty percent of the participants had also seen that food-related symptoms cause significant anxiety and always (or at least often) result in an elimination diet. A similar proportion reported that potentially food-related symptoms or eczema in a child under the age of one year resulted in an extra call or a visit to health care. Therefore, it is likely that matters related to infant nutrition, FA, and AD cause a significant burden to families with small children and to the health care system.

Although our survey for the parents of 1-year-old children was fairly small (n=248), it offers three important and timely observations at the population level: Firstly, all but three babies had received breast milk and 65% of them were exclusively breastfed until at least the age of four months and 17% until the age of six months (data not shown). Secondly, at least one food substance was intentionally avoided in a quarter of the children (57/248) during the first year of life. Four percent of all the babies had experienced immediate symptoms potentially related to food ingestion (any food) and close to 40% had experienced delayed symptoms during their first year of life, resulting in avoidance of one or more food substances in about 40% of these children. Furthermore, the incidence of parent-reported, doctor-diagnosed FA was 4% by the age of one year (only half of these had experienced immediate symptoms). Therefore, more than 80% of the avoidance diets (including 13 subjects without symptoms and 34 subjects without doctor-verified FA diagnoses) are unnecessary, according to current national and international clinical care guidelines. These children make up as much as 20% of the subjects in the present study. Thirdly, parent-reported, doctor-diagnosed AD was present in 13% by the age of one year, and most had been treated with topical corticosteroids. However, these treatments were also used in 10% of children with no skin symptoms, a remarkable divergence from current care guidelines. Taken together, these results might reflect the lack of practical tools in frontline health care or poor acquaintance with and knowledge of the current care guidelines.

The availability of the health care system's primary care services is homogeneous throughout Finland, in both rural and urban areas. Therefore, it is very likely that the current results can be extrapolated to apply to the whole country. On the other hand, as only 64% of the PHNs, 37% of the GPs and 31% of the families returned the questionnaires, we cannot be certain that the respondents are fully representative of the population. Their self-selection as participants may indicate a higher confidence of knowledge or a higher level of education and so may be somewhat biased.

In conclusion, professionals working in primary health care have a crucial role in providing information to families regarding infant feeding practices, food-related symptoms, FA, and AD. However, our present results suggest that the observed significant variation in knowledge, attitudes and beliefs may result in heterogeneous guidance practices, person-to-person variation, and confusion among both professionals and families. We also found several alarming gaps and heterogeneity in many areas of knowledge; these may jeopardize the treatment of FA and AD. In addition to further postgraduate training,12–14 simple and unambiguous practical tools, designed for primary care, are urgently needed in order to translate current guidelines into the practical health benefits at the population level.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest.

We thank all the primary care health professionals and the parents of the children attending this survey. This work was supported by the research grants from the Alma and K.A. Snellman Foundation, the Finnish Medical Association, the Allergy Research Foundation and the Finnish Pediatric Research Foundation.