The long-term efficacy of corticosteroids to prevent atopic dermatitis (AD) relapses has partially been addressed in children. This study compared an intermittent dosing regimen of fluticasone propionate (FP) cream 0.05% with its vehicle base in reducing the risk of relapse in children with stabilized AD.

MethodsA randomized controlled, multicentric, double-blind trial was conducted. Children (2–10 years) with mild/moderate AD (exclusion criteria: >30% affected body surface area and/or head) were enrolled into an Open-label Stabilization Phase (OSP) of up to 2 weeks on twice daily FP. Those who achieved treatment success entered the Double-blind Maintenance Phase (DMP). They were randomly allocated to receive FP or vehicle twice-weekly on consecutive days for 16 weeks. The primary study endpoint was relapse rate; time to relapse and severity of disease were also studied. Kaplan–Meier estimates were calculated.

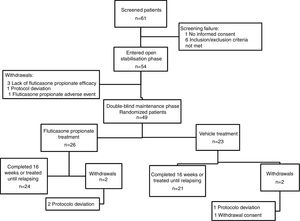

ResultsFifty-four patients (29 girls) entered the OSP (23 mild AD) and 49 (26 girls) continued into the DMP. Mean age was 5.5 (SD: 2.8) and 5.1 (SD: 2.3) yrs for FP and vehicle groups, respectively. Four patients withdrew from the DMP (two in every group). Patients treated with FP twice weekly had a 2.7 fold lower risk of experiencing a relapse than patients treated with vehicle (relative risk 2.72, SD: 1.28; p=0.034). FP was also superior to vehicle for delaying time to relapse. Both treatment therapies were well tolerated.

ConclusionThis long-term study shows that twice weekly FP provides an effective maintenance treatment to control the risk of relapse in children with AD.

One of the most troublesome features of atopic dermatitis (AD) is its chronic relapsing nature. Corticosteroids were an efficient topical therapy for the acute treatment of AD, but topical calcineurin inhibitors have provided alternatives although these remain expensive and adverse effects from long-term use are unclear.1,2 Moreover, traditional AD management is based on treating active disease but several data reports have suggested that topical treatment when a patient is not having active disease may be helpful.3 Hence, some clinical studies with non-daily topical antiinflamatory medications have been carried out, but the long-term efficacy and potential of corticosteroids to reduce or prevent relapses have only partially been addressed, especially in children.4–6

On the other hand, fluticasone 0.05% cream is a potent topical corticosteroid with a low systemic absorption and rapid metabolism and clearance, properties which shape a low potential to cause systemic adverse effects. Additionally, the safety of this corticosteroid has been evaluated in paediatric patients where one has to be especially careful given the higher ratio of skin surface area to body mass.7,8 In Spain fluticasone 0.05% cream is commercialized but only for acute treatment. Overall further studies were needed to test efficacy and safety in preventive AD relapsing in children.

This study was designed to compare an intermittent dosing regimen of fluticasone propionate (FP) cream 0.05% (twice per week) with its vehicle base in reducing the risk of relapse in paediatric subjects with stabilized AD.

MethodsSetting and patientsThe study was conducted in Spain with the participation of 20 centres of primary care and Dermatological Service, Allergic Unit and Clinical Pharmacology Unit of a General Hospital in Valencia between 2009 and 2012.

We calculated that at least 14 children/group were necessary to detect a delta=5 assuming α=0.01 two tails and β=0.05. The final sample size by group was established as 33 by considering it not to be a small sample, plus 10% of withdrawals in each group. Since Berth-Jones et al.5 reported that at least 60% of patient achieved treatment success, we estimated a recruitment of 100 patients in an initial phase that to be randomized in two arms.

Children, aged two to ten years, with mild or moderate AD according to the Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis system9 (SCORAD up to 50) were enrolled into an Open-label Stabilization Phase (OSP) on treatment with twice daily FP cream 0.05%. All parents or relatives provided written informed consent and if feasible the children also gave their consent.

We considered remission if SCORAD <5 or ≥75% reduction of initial SCORAD. Those children were randomized in a Double-blind Maintenance Phase (DMP).

Exclusion criteria were any head involvement or >30% of body or head combined body surface area, patients with any medical condition for which topical corticosteroids were contraindicated (e.g. fluticasone allergy, rosacea, acne vulgaris, perioral dermatitis or severe fungal, bacterial, viral or parasitic infections), those with other dermatological conditions that may have prevented accurate assessment of AD and those receiving any concomitant medications that might have affected the study's outcome (e.g. systemic glucocorticoid drugs, immunosuppressive agents or antihistamine drugs) and whatever condition that was unadvised at their inclusion (e.g. cancer or mental illness).

Study design and interventionsThis multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel-group study consisted of two phases. Children were enrolled into an initial OSP on treatment with twice daily FP cream 0.05% up to 2 weeks; those children who achieved treatment success in OSP entered the DMP. They were randomly allocated to receive FP or vehicle (PFC O/W Base® – Guinama S.L.U., Propyleneglycol and Aqua conservans) twice weekly on consecutive days for 16 weeks or at relapse, in which case they were withdrawn from the study. The families were contacted by telephone in week 8th and in week 16th were cited for the final visit.

The patients were requested to maintain the emollient cream. Systemic corticoids, immunomodulators drugs and antihistamines H1 were not allowed along DMP.

Randomization was generated by a random number table; the list was produced by the statistical service of the Contract Research Organization (CRO. EXPERIOR SL). A blinded copy and clinical trial coded medication were received and stored by the clinical trials pharmacist at Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (CHGUV). The pharmacist dispensed the research drugs packs according with the research assistants that used consecutively numbered packs to allocate new participants to treatment groups. Participants and researchers were blinded to group assignment until the study completion.

Main outcome measuresThe primary study endpoint was a relapse rate of AD, defined as an SCORAD >5 or ≥25% initial SCORAD. Secondary endpoints included the time to relapse calculated by number of days and clinical manifestation and severity of disease according with SCORAD.

Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events. Causal relationship of the clinical event to the use of the medication studied was assessed by clinical researchers. The adverse cutaneous reactions related with corticosteroid treatment were particularly considered (skin atrophy, telangiectasia, striae and hypertrichosis).

Statistical analysisThe crude relative risk and the Mantel–Haenszel estimate of the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were calculated. The distribution of time to relapse was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between treatment groups were tested using Log Rank (Mantel–Cox). A Student's t test was used to assess differences in the variation of SCORAD values between groups. An intention-to-treat analysis was done.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at all participating centres and all patients’ parents provided their written informed consent.

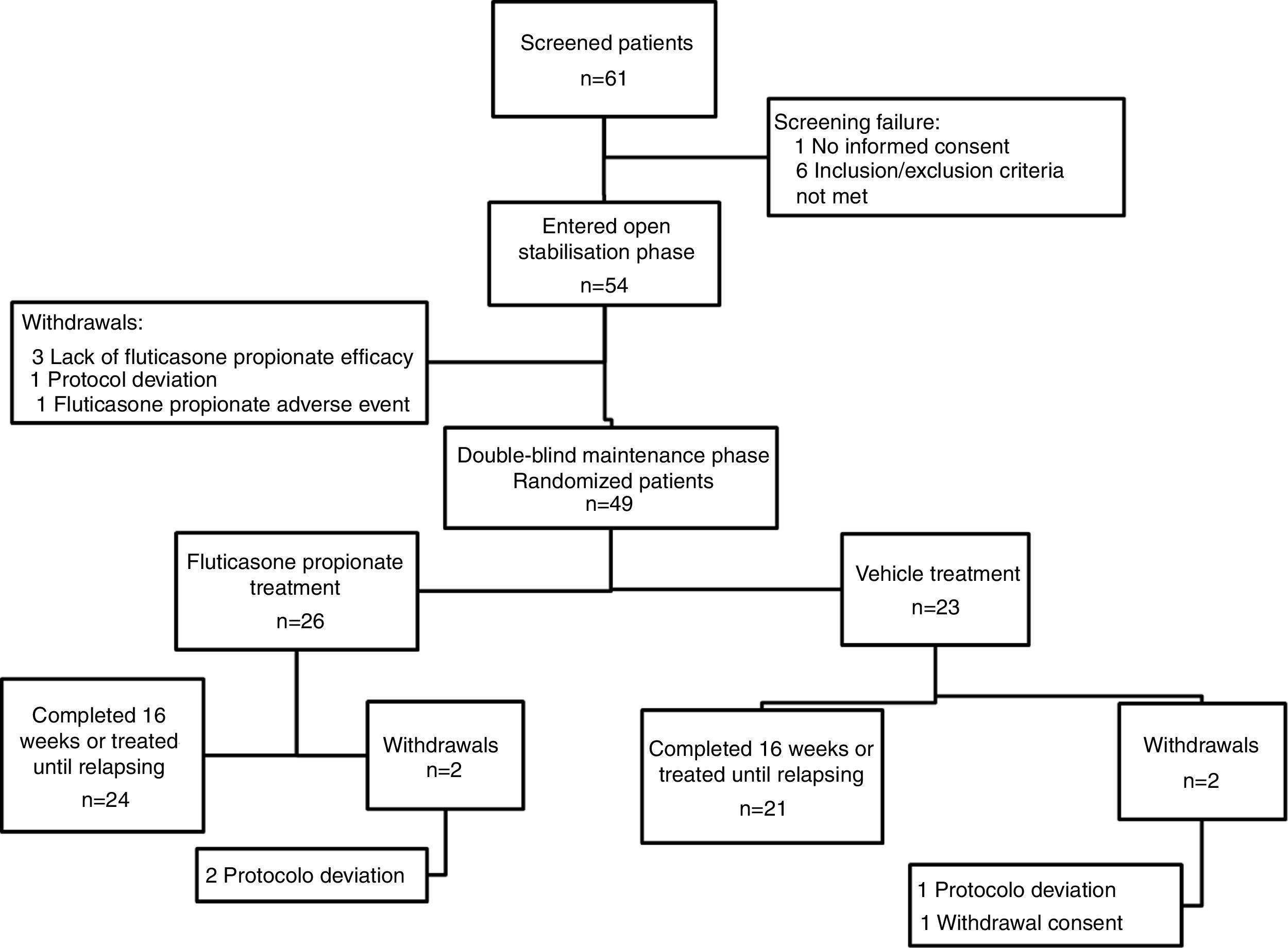

ResultsA total of 61 patients were assessed for eligibility, of these children, seven had failed screening. Hence, fifty-four patients entered the OSP, of them 49 continued into the DMP and were randomized (twenty six were in the FP group). Four patients withdrew from the DMP (two in the FP group and two in the vehicle group) (Fig. 1). The period of recruitment and follow-up was from December 2009 to March 2012. The study was prematurely ended because financial resources were limited and the recruitment of participants was scarce. On the other hand, the number of children included in the DMP was higher than the minimum calculated.

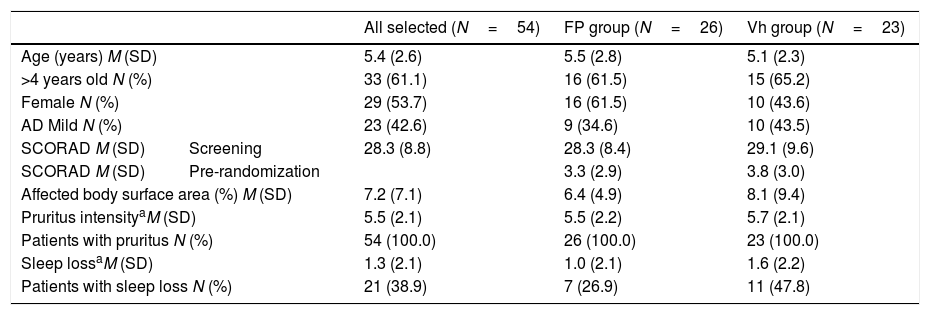

Demographic details and disease characteristics of the children are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In DMP the ages ranged from two to ten years and there were no differences between groups in baseline demographics and disease severity, with the exception of a difference between numbers of patients with sleep loss.

Demographic and disease characteristics of children with atopic dermatitis at screening in all recluted patients and in the randomized groups.

| All selected (N=54) | FP group (N=26) | Vh group (N=23) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) M (SD) | 5.4 (2.6) | 5.5 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.3) | |

| >4 years old N (%) | 33 (61.1) | 16 (61.5) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Female N (%) | 29 (53.7) | 16 (61.5) | 10 (43.6) | |

| AD Mild N (%) | 23 (42.6) | 9 (34.6) | 10 (43.5) | |

| SCORAD M (SD) | Screening | 28.3 (8.8) | 28.3 (8.4) | 29.1 (9.6) |

| SCORAD M (SD) | Pre-randomization | 3.3 (2.9) | 3.8 (3.0) | |

| Affected body surface area (%) M (SD) | 7.2 (7.1) | 6.4 (4.9) | 8.1 (9.4) | |

| Pruritus intensityaM (SD) | 5.5 (2.1) | 5.5 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.1) | |

| Patients with pruritus N (%) | 54 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | |

| Sleep lossaM (SD) | 1.3 (2.1) | 1.0 (2.1) | 1.6 (2.2) | |

| Patients with sleep loss N (%) | 21 (38.9) | 7 (26.9) | 11 (47.8) | |

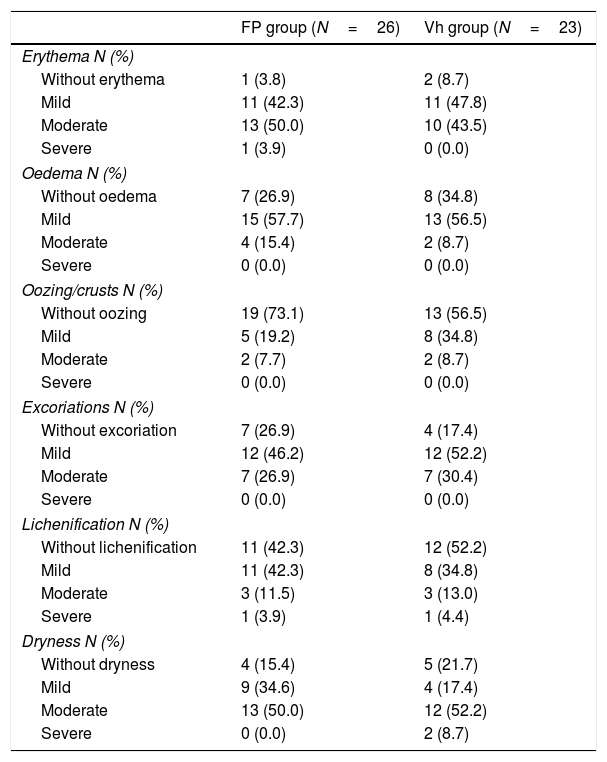

Clinical manifestation and severity of atopic dermatitis at the beginning of the study of the randomized children in the Double-blind Maintenance Phase.

| FP group (N=26) | Vh group (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Erythema N (%) | ||

| Without erythema | 1 (3.8) | 2 (8.7) |

| Mild | 11 (42.3) | 11 (47.8) |

| Moderate | 13 (50.0) | 10 (43.5) |

| Severe | 1 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Oedema N (%) | ||

| Without oedema | 7 (26.9) | 8 (34.8) |

| Mild | 15 (57.7) | 13 (56.5) |

| Moderate | 4 (15.4) | 2 (8.7) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Oozing/crusts N (%) | ||

| Without oozing | 19 (73.1) | 13 (56.5) |

| Mild | 5 (19.2) | 8 (34.8) |

| Moderate | 2 (7.7) | 2 (8.7) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Excoriations N (%) | ||

| Without excoriation | 7 (26.9) | 4 (17.4) |

| Mild | 12 (46.2) | 12 (52.2) |

| Moderate | 7 (26.9) | 7 (30.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lichenification N (%) | ||

| Without lichenification | 11 (42.3) | 12 (52.2) |

| Mild | 11 (42.3) | 8 (34.8) |

| Moderate | 3 (11.5) | 3 (13.0) |

| Severe | 1 (3.9) | 1 (4.4) |

| Dryness N (%) | ||

| Without dryness | 4 (15.4) | 5 (21.7) |

| Mild | 9 (34.6) | 4 (17.4) |

| Moderate | 13 (50.0) | 12 (52.2) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) |

FP: fluticasone propionate; N: number of patients; Vh: vehicle.

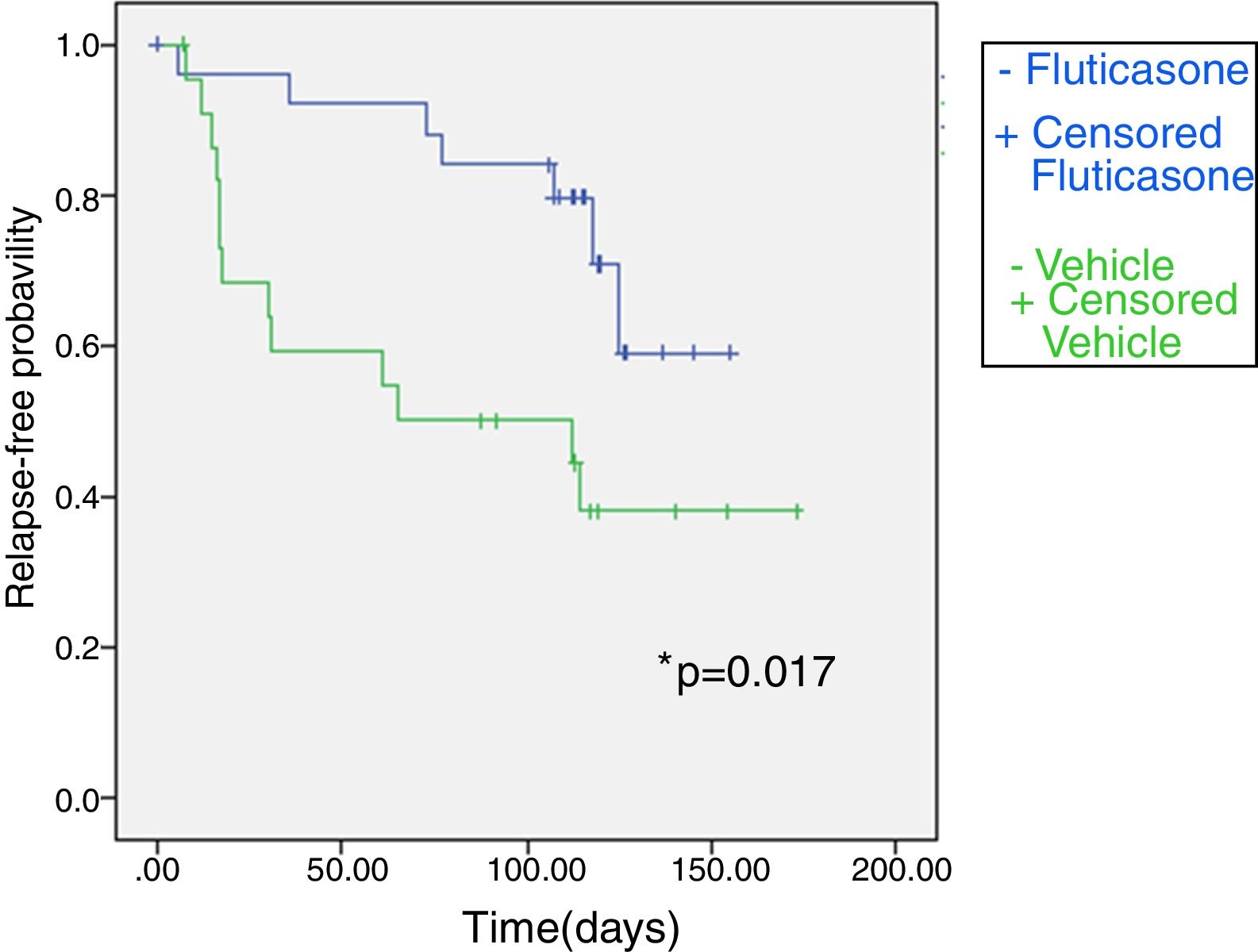

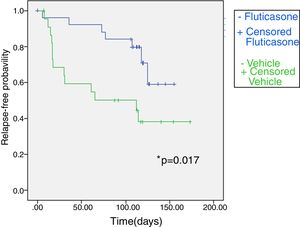

Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier plot for time to relapse. Overall, 13 of 23 patients (56.5%) in the vehicle group and 7 of 26 (26.9%) in the FP group had a relapse. Patients treated with FP twice weekly had a 2.7 fold lower risk of experiencing a relapse than patients treated with vehicle (relative risk 2.72, CI 95% 0.21–5.23; p=0.034). The duration of the relapse-free period was longer in the FP group than in the vehicle group (non-parametrical log rank test: χ2=5.716; p=0.017). The median time to relapse in twice weekly fluticasone propionate exceeded 16 weeks (the duration of the study), whereas in a vehicle group it was 65.0 (0.0–180.6) days.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for fluticasone treatment (N=26) and vehicle treatment group (N=23) showing time (days) to relapse during the maintenance phase in atopic dermatitis children. Treatment with fluticasone propionate is significantly better according to non-parametrical log rank test, significant level=0.017.

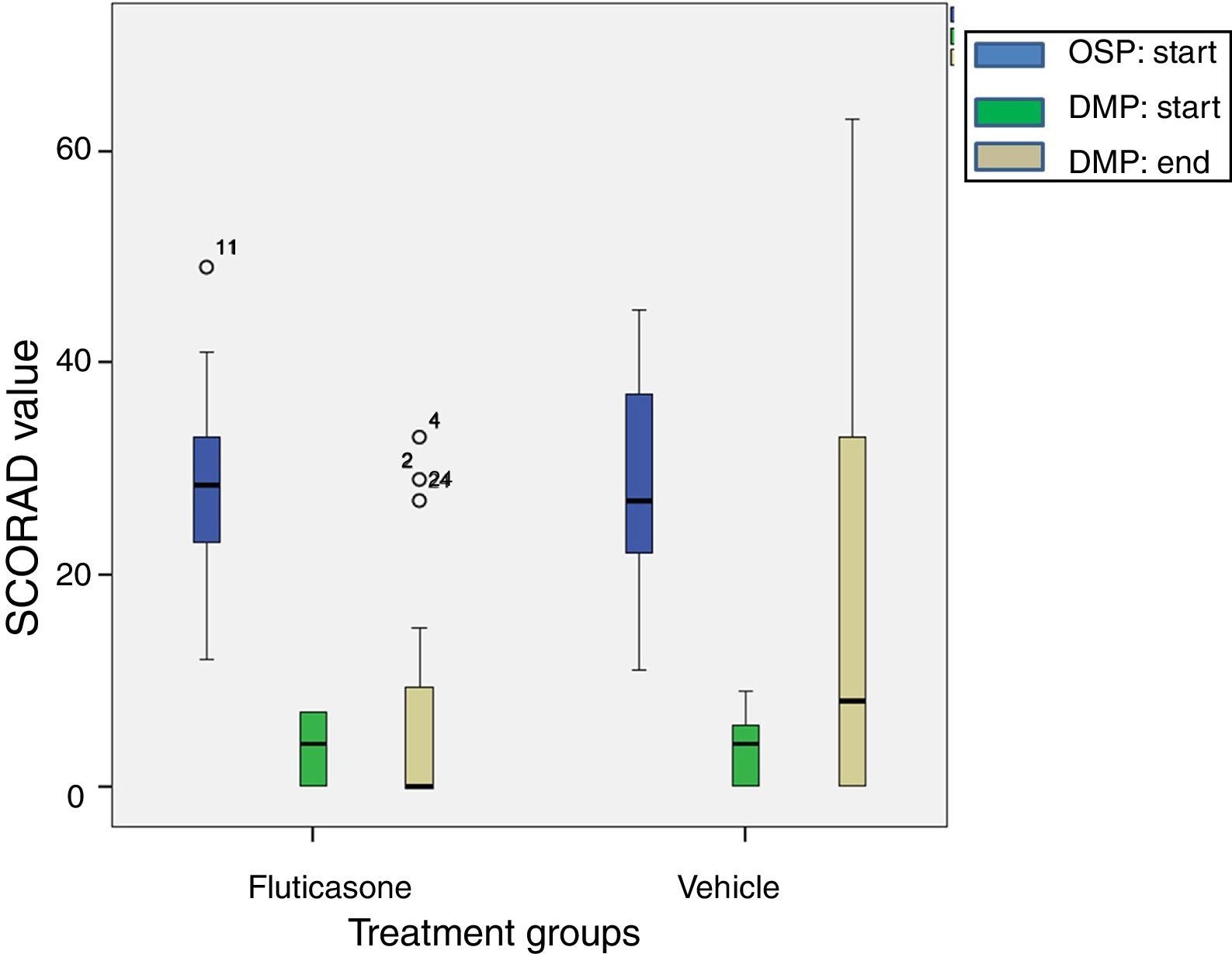

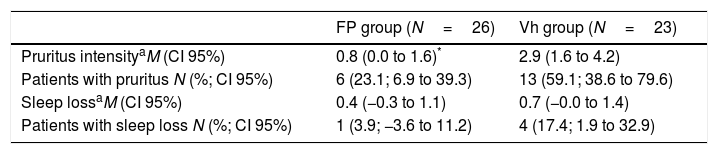

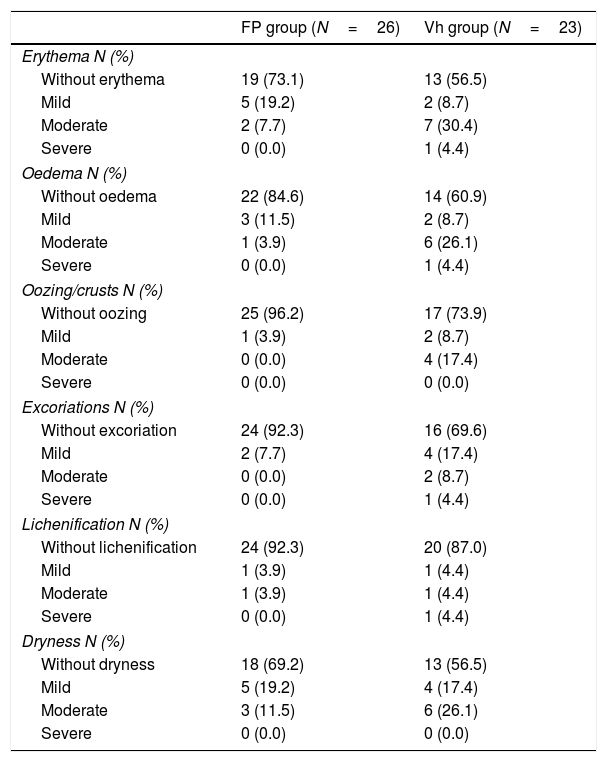

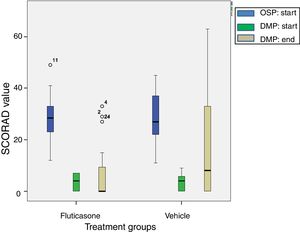

The reduction of SCORAD intensity between initial (OSP) and last values (end of DMP) was significantly higher in the FP group with respect to the vehicle group (mean difference 9.3; CI 95% 0.49–18.15; t=2.3; p=0.03). These results are shown in Fig. 3. Intensity of pruritus decreased compared with the baseline in both treatment groups. However, the improvement was better in the FP group (0.8; CI 95% 0.03–1.57) than in the vehicle group (2.9; CI 95% 1.63–4.17). In other way, the number of patient without pruritus (FP group 20 patients vs vehicle group 10 patients) and with less severity of pruritus were greater in the FP group. In a different way, the sleep loss and the number of patients with sleep loss apparently improved in the FP group, it did not reach the statistical significance (Table 3). Similarly, the clinical manifestations had better results in the FP group in all categories evaluated (Table 4).

A boxplot of SCORAD values for both treatment groups at beginning of Open-label Stabilization Phase (OSP; N=49). After treatment success, 26 children were randomized to fluticasone treatment and 23 to vehicle treatment to start the Double-blind Maintenance Phase (DMP). At the end of the DMP, 24 children stayed in the fluticasone treatment group and 21 to the vehicle treatment group. The digit close to the circle (data) means the number case. The reduction in SCORAD value with fluticasone propionate treatment is significantly higher according to Student's t test, p=0.03.

SCORAD values for pruritus and sleep loss of the atopic dermatitis children at the end of the Double-blind Maintenance Phase.

| FP group (N=26) | Vh group (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pruritus intensityaM (CI 95%) | 0.8 (0.0 to 1.6)* | 2.9 (1.6 to 4.2) |

| Patients with pruritus N (%; CI 95%) | 6 (23.1; 6.9 to 39.3) | 13 (59.1; 38.6 to 79.6) |

| Sleep lossaM (CI 95%) | 0.4 (−0.3 to 1.1) | 0.7 (−0.0 to 1.4) |

| Patients with sleep loss N (%; CI 95%) | 1 (3.9; −3.6 to 11.2) | 4 (17.4; 1.9 to 32.9) |

SCORAD values for clinical manifestation and severity of atopic dermatitis children at the end of the Double-blind Maintenance Phase.

| FP group (N=26) | Vh group (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Erythema N (%) | ||

| Without erythema | 19 (73.1) | 13 (56.5) |

| Mild | 5 (19.2) | 2 (8.7) |

| Moderate | 2 (7.7) | 7 (30.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.4) |

| Oedema N (%) | ||

| Without oedema | 22 (84.6) | 14 (60.9) |

| Mild | 3 (11.5) | 2 (8.7) |

| Moderate | 1 (3.9) | 6 (26.1) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.4) |

| Oozing/crusts N (%) | ||

| Without oozing | 25 (96.2) | 17 (73.9) |

| Mild | 1 (3.9) | 2 (8.7) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | 4 (17.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Excoriations N (%) | ||

| Without excoriation | 24 (92.3) | 16 (69.6) |

| Mild | 2 (7.7) | 4 (17.4) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.4) |

| Lichenification N (%) | ||

| Without lichenification | 24 (92.3) | 20 (87.0) |

| Mild | 1 (3.9) | 1 (4.4) |

| Moderate | 1 (3.9) | 1 (4.4) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.4) |

| Dryness N (%) | ||

| Without dryness | 18 (69.2) | 13 (56.5) |

| Mild | 5 (19.2) | 4 (17.4) |

| Moderate | 3 (11.5) | 6 (26.1) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

FP: fluticasone propionate; N: number of patients; Vh: vehicle.

Therapy with both treatments was well tolerated. During the entire study, 21 of 54 patients (38.9%) reported at least one adverse event (AE), of which only one (skin itch, eczema and erythema on the smeared cream area) was related to the study drug and it happened during the OSP. During the DMP, 9 (34.8%) patients reported at least one AE in the FP group and 11 (47.8%) in the vehicle group. Of these, two serious AEs were reported, one aphthous stomatitis in the FP group and one mastoiditis in the vehicle group. No AEs during the DMP were considered related to the drug studied.

DiscussionAtopic dermatitis is a chronic disease without a cure, so new approaches that have both more efficacy and safety are needed. Long-term, intermittent applications of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppression drugs are a new proposal under investigation in relapse prevention. Moreover, children are therapeutic orphans and drug investigation is necessary.10 Fluticasone is a well-known corticoid which has demonstrated efficacy and security in children when it is used topically in skin disease.1,5,6,8,11 Glazenburg et al.12 had described the fluticasone efficacy in the prevention of flare in children with moderate to severe AD using ointment; the difference with the present study is the severity of the disease and the pharmaceutical preparation. Schmitt et al.4 in a systematic review point out that care should be taken with the extrapolation of the results to primary setting because the severity of the AD in the patients studied is different. Moreover, they also described a different efficacy between ointment and cream fluticasone propionate. Additionally, in Spain the fluticasone propionate is only commercialized as cream.7,10 In this context, we had investigated the efficacy of fluticasone cream twice a week during 16 weeks in children with mild to moderate AD to prevent relapses.

According to Tang et al.13 the proportion of patients (90.7%) that achieved remission at the initial OSP on treatment with twice daily FP cream 0.05% up to 2 weeks was similar to those described for this compound in different setting, although Van der Meer et al.14 described remissions rate of 50% may be due to higher severity of AD in the population studied.

In the present study, improvement in all efficacy variables assessed was observed in the group of children with AD who were treated with 0.05% FP cream twice a week compared with the placebo group. In the 16th week of the observation period, children in the FP group had a 2.7 fold lower risk of experiencing relapse, compared with the vehicle. The overall relapse was also lower with FP (26.9%) compared with vehicle treatment (56.5%). Furthermore, in agreement with other authors in this study the median time to relapse on FP group could not be estimated but exceeded 16 weeks, while those patients treated with vehicle relapsed after 9 weeks.6,14 In addition, since the study was conducted on outpatients with mild to moderate AD, the FP could be particularly indicated for the treatment of patients in a primary care setting. A further advantage is the low cost of this kind of treatment that it could reduce the economic burden of the disease.

The relapses also show less SCORAD intensity value in the study group, this result is comparable with those obtained elsewhere at the end of the double-blind maintenance phase.5,7,15 In a similar way, the sleep quality improved in the FP group, although the number of patient with sleep loss at the baseline was higher in the vehicle groups so this result is difficult to discuss.

Our results with respect to safety parameters are in agreement with those obtained by other authors.5,8,14–16 FP cream, twice a week, has been shown to be safe in acute and maintenance treatment of patients with mild to moderate AD. Regarding the adverse effects of corticosteroids, in our setting, there are some worries about their use in children. In this sense, the safety of an intermitted course of topical corticosteroids contributes to remove the fear of health professionals, parents and patients in its therapeutic utilization in this condition.

The pragmatic design, long duration, and the use of validated scales for the diagnosis and severity assessment of atopic dermatitis in an outpatient setting was the strengths of the present study. The design, in two consecutive phases, supports its validity. Hence, in agreement with other authors, at the end of the first two weeks of treatment 49 patients achieved clear or almost clear status, according to criteria selection they subsequently entered the long-term phase of the study. On the other hand, it is necessary to point out that this study was prematurely terminated because patient recruitment was very slow and the economic grant had ended, nonetheless the number of recruited patients was enough according to the estimated sample size, so this study can be conclusive with certainty. Other possible limitations of the study could be that the present results are not generalizable to cases with severe AD. The trial duration made it difficult to detect long-term side effects.

Clinical trial registrationEudraCT Number: 2008-005360-14; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01772056.

Topical steroids have been shown to be a safe and effective short-term therapy on children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

There is a generalized thought of fear about whether corticoids will be safe on long-term treatments.

Hence, new strategies have being developed.

What this study addsTwice a week topical fluticasone propionate is effective in decreasing the risk of atopic dermatitis (AD) relapse in children in a primary care setting.

This treatment positively affects clinical features of AD.

This strategy is safe when used as a long-term maintenance therapy.

Elena Rubio-Gomis, and Inocencia Martinez-Mir conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, carried out the analyses, interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Francisco J. Morales-Olivas, and Vicente Palop-Larrea conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to the interpretation of the data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Antonio Martorell-Aragones conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection at his centre, contributed to the interpretation of the data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Alejandro Bernalte-Sesé, and Isabel Febrer participated in the designed the data collection instruments, acquisition of data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Juan C. Cerda-Mir, Pedro Polo-Martín, Laura Aranda-Grau, MªVictoria Planelles-Cantarino and Mercedes Loriente-Tur coordinated and supervised data collection at their centres, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Inmaculada Llosa-Cortes, MªJose Tejedor-Sanz, Juan C. Julia-Benito, Trinidad Alvarez de Laviada Mulero, Esther Apolinar-Valiente, Antonio M. Abella-Bazataqui, Irene Alvarez-Gonzalez, Cristina Morales-Carpi, MªEnriqueta Burches-Greus, Ana B. Ferrer-Bautista, Ruben Felix-Toledo, Dolores Marmaneu-Laguia, Victoria E. Garcia-Martinez, MªAntonia Beltran-Marques and Begoña Rodriguez-Gracia contributed to the conceptualization and designs of the study, collection data, revised and approved the final manuscript as submitted

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The undersigned authors warrant that the article is original; it has not been published previously and is not under consideration elsewhere.

Conflict of interestAuthors have no financial or personal relationships relevant to this article to disclose and they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study (EC08/00004) was conducted with a grant from ISCIII – Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain.