Since the first intents of allergen immunotherapy (AIT), now already over a hundred years ago by Leonard Noon, AIT is still the sole disease modifying treatment available for patients with allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, allergic asthma, atopic dermatitis and hymenoptera venom allergy. The first publication on AIT in 1911 by Noon from the St. Mary's Hospital in London, described the reduction of sensitivity in nasal challenge testing of hay fever patients, allergic to grass pollen, after repetitive subcutaneous administration of a grass pollen extract.1 Misfortunately, Noon never could see if the patients really improved their symptoms during the grass-pollen season, as he died of tuberculosis before the start of the season. His colleague, J Freeman, continued his work and subsequently published the reduction in symptoms during the grass pollen season of Noon's AIT patients.2 Since, AIT has gone through better and worse times, but through the difficult years during the 40–50ies, when AIT was practically banished, it made it to the 60ies when the first controlled trials saw the light, both in the old continent and in the United States of America (USA).3,4 The first dose–response effect for AIT was shown with Ragweed pollen by Lowell and Franklin.5,6 During those same years doctor Mary Loveless showed that the administration of wasp and honeybee venom could reduce the frequency and severity of sting reactions in hymenoptera venom allergic patients, as opposed to the poor performance of the whole body extract, typically used in those days.7,8 The efficacy of AIT in allergic asthma was demonstrated by Johnstone et al. a few years later: multi-allergen AIT reduced the frequency of asthma symptoms and asthma attacks in a dose–response manner.9

Since 1986 sublingual AIT showed to be effective as well, and from that moment onward the evidence for this treatment modality has become very solid,10 demonstrating even long-term effect, be it the evidence here is not as robust as for the direct efficacy.11

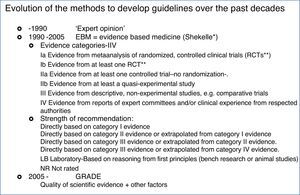

The history of guidelines for medical practiceIn parallel with AIT, clinical practice guideline-making has also been evolving, but most so only over the past decades, see Box 1. The first guidelines dating from the 70–80ies were mostly consensus documents, narrating recommendations based on the clinical experience of well-recognized experts. By the end of the past millennium evidence based medicine became stronger and Shekelle proposed a system in which the clinical recommendations were directly linked to the level of evidence. In the Shekelle system the quality of the evidence was directly related to the study design, with metanalyses having the highest category of evidence (1a), directly followed by randomized clinical trials (category 1b). As such, in the Shekelle system it is possible to respond to a certain clinical question with a level A recommendation, based on only one clinical trial, in which active and control patients are openly randomized, without the need for a placebo group. In this same line of acting a doubleblind, placebo controlled clinical trial, even though completely underpowered, can be able to generate a level A recommendation in the Shekelle system.

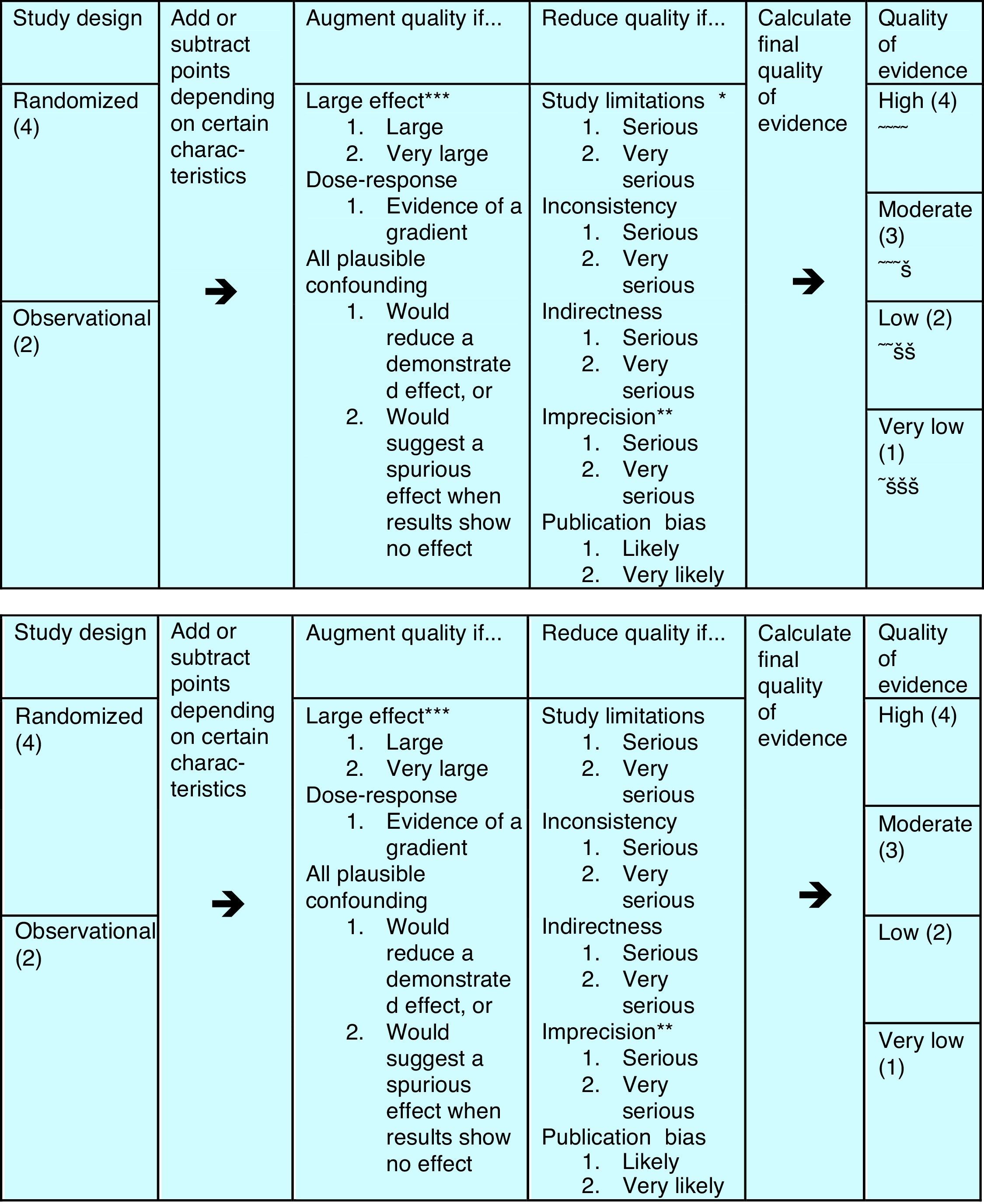

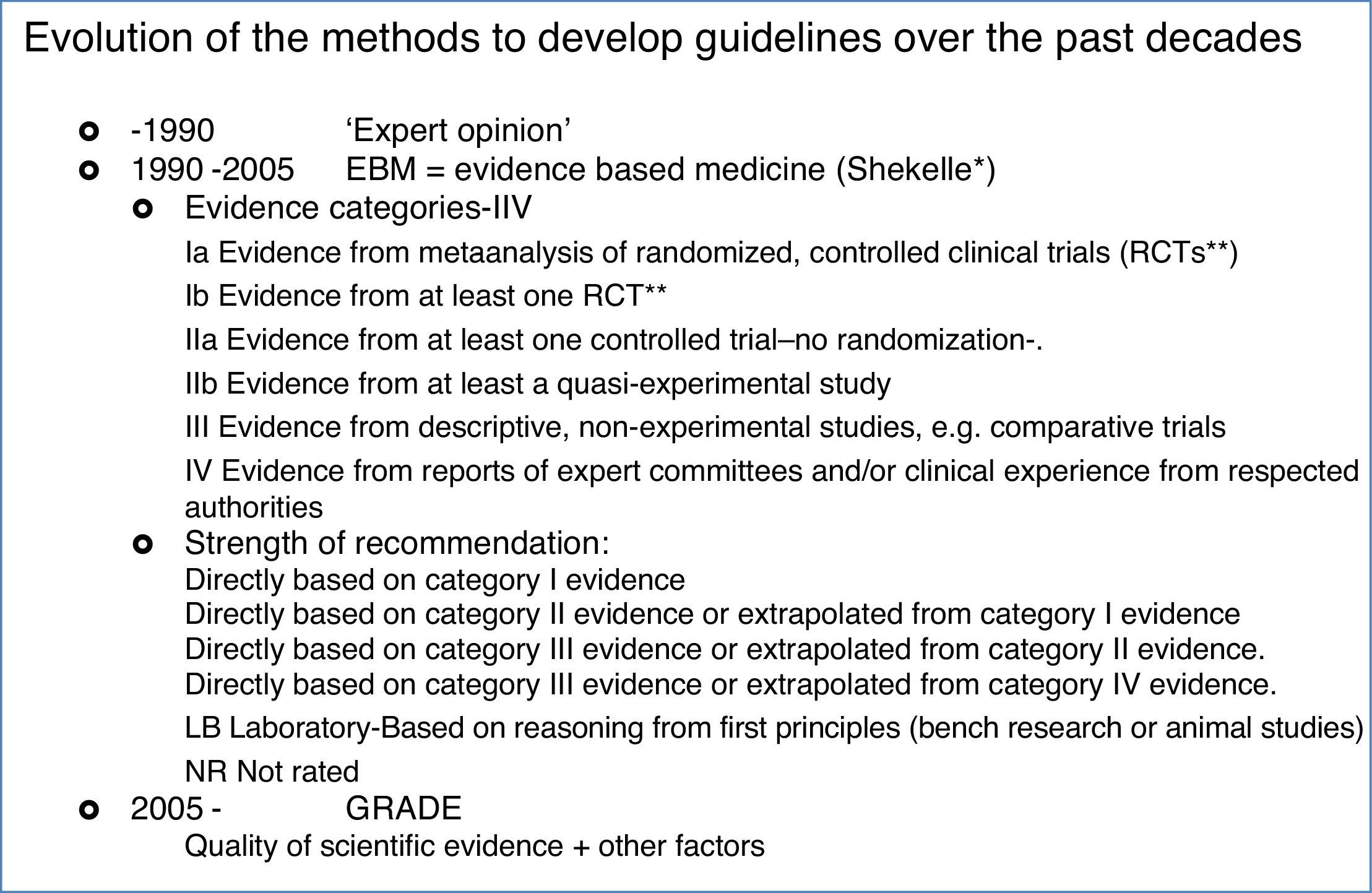

That's why a group of methodologists from the McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, developed in 2005 the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system, which has been the leading system of guideline development in all areas of the medical discipline since. In GRADE the recommendations are the core part of the system, and the evidence is only one pillar that sustains a recommendation. Apart from the evidence, the safety of the treatment, the cost and the patients’ preference are the other three pillars on which the recommendations are built. Moreover, the quality evaluation of the evidence is more complete, taking into account other factors, apart from the study design, that can help to enhance or reduce quality of a study, see Fig. 1. As a consequence, evaluating with GRADE not all double-blind placebo controlled trials are of high quality, nor all observational studies of low quality, and all can contribute to the evidence needed in a guideline.

Even though the GRADE system also has its flaws and is still in continuous improvement, since its creation in 2005, it has been considered the most reliable guideline development system.

The evidence can be assigned from 1 to 4 bullets, rating it from very low to high quality evidence. The study design is only the starting point – see left part – from where quality points can be added or subtracted according to further details in study design, elaboration of the results and publication.

Assessing the quality of medical guidelines: the AGREE II toolWith the appearance of more and more guidelines dealing with a variety of medical issues, from global ones, to regional and national ones lately two further problems with guidelines are becoming apparent: 1. The quality, 2. The poor applicability. To help the medical community differentiate between the quality of the different guidelines, again methodologists of the McMaster University developed a tool to grade guidelines quality: AGREE, in 2010 improved into AGREE II.

AGREE II consists of six domains, that evaluate:

- •

Domain 1. Scope and Purpose

- •

Domain 2. Stakeholder Involvement

- •

Domain 3. Rigor of Development*

- •

Domain 4. Clarity of Presentation

- •

Domain 5. Applicability

- •

Domain 6. Editorial Independence

*(process to gather and synthesize the evidence, the methods to formulate the recommendations and to update them)

Each domain consisting of several questions that investigators should pose to the guideline; for example ‘The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups’. Each item is evaluated from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree).

One of the strong parts of AGREE II is the emphasis it puts on the enhancement of guideline dissemination and applicability. Already in the second domain it stresses the importance of a broad stakeholder involvement: right from the early phases of the development of a guideline not only the specialists, but also primary care doctors, pharmacists, nurses and industry partners and legislators should be involved. This is re-enforced with the fifth domain: applicability, that asks for a separate chapter in the guideline that addresses the barriers and facilitators for its implementation and how these should be tackled, the economic implications of the management recommendations in the guideline and the monitoring and auditing of its impact.

This makes is clear that the focus of a guideline is not solely to transmit the most up-to-date highly scientific knowledge, but to guide the clinician in the improvement of his every day practice, delivering evidence-based knowledge in an understandable manner, together with the tools how to apply this.

Guidelines and practice parameters on AITWith the growing interest in allergen immunotherapy, the ever-growing knowledge of its mechanisms and consequences, a broad variety of AIT practices can be detected worldwide. Local differences can be found in sensitization patterns of allergic patients and the severity of the allergic reactions, the natural exposure of the patient, but also in the allergen extracts available. In intent to harmonize, allergy specialists have produced AIT guidelines, first regional ones and lately even global ones, coordinated by the World Allergy Organization. There are also national ones, some of them directed to AIT in general, others more focused on specific national issues related to AIT, as for example the Spanish Consensus on AIT in poly-sensitized allergic patients.12 At the moment more than thirty AIT guidelines and consensuses exist worldwide.

The first AIT guidelines were indeed more consensus documents, some of them directly sponsored by one of the partners of the pharmaceutical industry.13 Since the start of the new millennium AIT guidelines have been more evidence-based, using the Shekelle system from evidence directly to recommendation. This might lead to recommendations that are not based on solid evidence, as the following examples can show. The Practice Parameters on Allergen Immunotherapy from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, jointly with the American College and the Joint Council on Allergy, Asthma and Immunology publishes dosing tables in the document, with probably effective subcutaneous AIT doses.14 However, when reading carefully the footnote to the table it states that there do not exist any trials with US house dust mite extracts and that the studies, the dosing recommendations are based on, are all European studies, in which mostly alum absorbed extracts were administered. Looking further into the details these are studies from the 80 to 90ies, each of them with at most 20 patients in each of the active groups; all utilized extracts from ALK-Abelló, Denmark.15–17 The effective dose found in these trials contained 7mcg of the major allergen Der p 1, but no Der p 2 content was stated.16 The allergen extracts used in those days in Europe were whole mite culture products, with a Der p 1:Der p 2 ratio of about 10:1. Recently, the very low Der p 2 content in several European SLIT products has been confirmed again.18 However, the US extracts are pure mite body extracts, with a Der p 1:Der p 2 ratio close to 1:1.18,14 HDM allergic patients generally have similar amounts of specific IgE against both proteins, thus an extract with a cumulative group 1+2 content of 7+7=14mcg/mL has an allergic potency almost twice as much as an extract containing 7+0.7=7.7mcg/mL. Moreover, US extracts are aqueous, as opposed to most ALK-Abelló extracts from Europe that were alum-adsorbed. Thus, when a guideline gives recommendations these should be based on as high quality evidence as possible, and taking into account the adaptability of the evidence to the target population.

Another example is the claimed preventive effect of AIT. Several AIT guidelines, including the US Practice Parameters, state AIT prevents new sensitizations and the development of asthma in patients only suffering from allergic rhinitis. Several trials in which those preventive effects were studied are cited after these statements, however, without an evaluation of the quality and potential bias of these trials. As a consequence, it is not clear how certain we are of the preventive effect.

In a guideline based on GRADE first the total quality of the evidence and the risk of bias is evaluated. Based on this analysis finally recommendations/suggestions for a certain treatment option are given. In this line, in 2015 the EAACI decided to engage in the project of developing the European AIT guidelines. During the first phase the protocols for the systematic reviews were developed and published, e.g. for the preventive effect of AIT by Dhami et al.19 and for AIT in the treatment of allergic rhinitis by a different group, but again led by Dhami.20 Then, in the second phase the actual literature search and meta-analyses were conducted and published. 21 Now, in the third phase and based on the evidence from the meta-analyses, finally the guidelines are being developed. In the metanalyses of the prevention paper it becomes clear that there is solid evidence for the short-term (less than 2 years’) prevention of asthma in patients with only allergic rhinitis. However, there is only vague, doubtful evidence that indicates a trend of AIT reducing new sensitizations, because the interval of the odds ratio includes 1.21

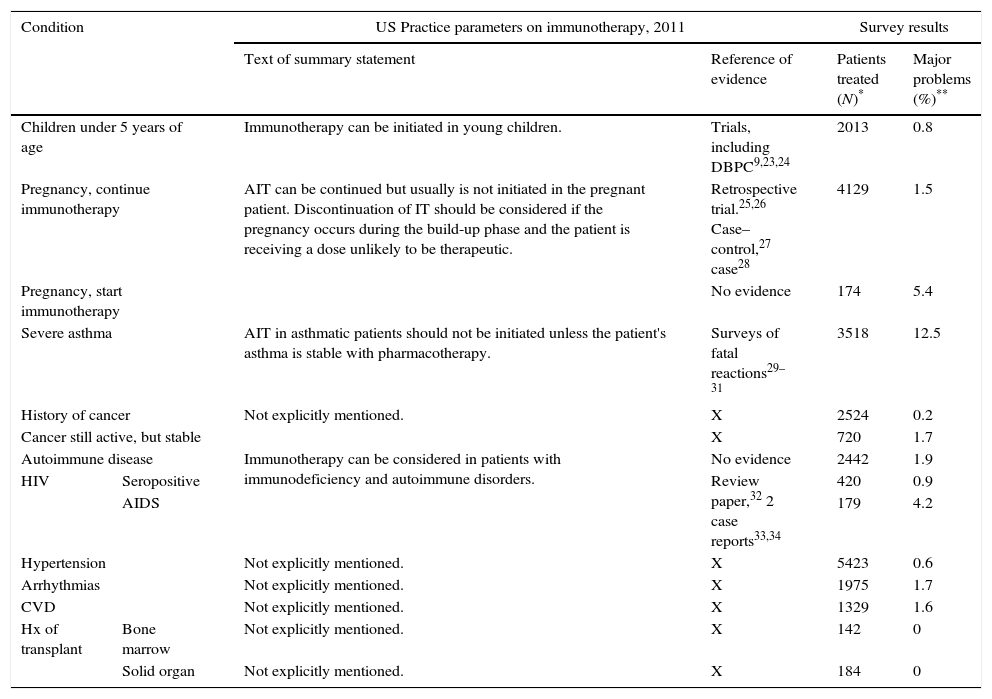

When observational studies could be of value in guidelinesOn certain issues it can be difficult, or even impossible, to obtain evidence from randomized controlled trials. Such is the case for AIT in patients with specific underlying conditions, e.g. a history of malignancy or organ transplantation, HIV seropositivity, AIDS, to name some. In Table 1 we review the recommendations one of the guidelines gives in these cases, and the evidence on which the recommendations are based (Table 1, column 3). For AIT in patients with conditions mentioned in the lower part of the table, hardly any evidence – if any at all – sustains the guideline recommendations. In the last column the results of a recently published observational survey among AAAAI members are transcribed.22 The survey asked the membership if they recalled to have had any patient on AIT who had one of the specific conditions, reviewing them one by one in the questionnaire. In case of a positive answer, the physicians was asked to mark the range indicating the total number of patients with such condition treated with AIT in the physician's clinic (1–4, 5–10 or >10). Column 4 reports the collective experience of the over 1000 AAAAI members who replied to the survey, with AIT in these patients, and in column 5 the physicians indicate if they had experienced major problems with each category of patients. Major problems were defined for the responders as activation of an underlying disease, systemic reactions secondary to SCIT, or discontinuation of SCIT for medical reasons. Although caution should be taken with retrospective data, as recall bias can always play a role, it seems there is a broad experience with AIT in patients who have had a malignancy, with hardly any major problems. A similar survey for VIT was conducted by the same group (Calabria 2016, accepted for publication AAP 2016) and in Europe a Task Force of EAACI also studied the same issue. (Rodriguez P, personal communication, submitted for publication.)

Relation of US practice parameters recommendations14 and survey results.

| Condition | US Practice parameters on immunotherapy, 2011 | Survey results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text of summary statement | Reference of evidence | Patients treated (N)* | Major problems (%)** | ||

| Children under 5 years of age | Immunotherapy can be initiated in young children. | Trials, including DBPC9,23,24 | 2013 | 0.8 | |

| Pregnancy, continue immunotherapy | AIT can be continued but usually is not initiated in the pregnant patient. Discontinuation of IT should be considered if the pregnancy occurs during the build-up phase and the patient is receiving a dose unlikely to be therapeutic. | Retrospective trial.25,26 Case–control,27 case28 | 4129 | 1.5 | |

| Pregnancy, start immunotherapy | No evidence | 174 | 5.4 | ||

| Severe asthma | AIT in asthmatic patients should not be initiated unless the patient's asthma is stable with pharmacotherapy. | Surveys of fatal reactions29–31 | 3518 | 12.5 | |

| History of cancer | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 2524 | 0.2 | |

| Cancer still active, but stable | X | 720 | 1.7 | ||

| Autoimmune disease | Immunotherapy can be considered in patients with immunodeficiency and autoimmune disorders. | No evidence | 2442 | 1.9 | |

| HIV | Seropositive | Review paper,32 2 case reports33,34 | 420 | 0.9 | |

| AIDS | 179 | 4.2 | |||

| Hypertension | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 5423 | 0.6 | |

| Arrhythmias | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 1975 | 1.7 | |

| CVD | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 1329 | 1.6 | |

| Hx of transplant | Bone marrow | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 142 | 0 |

| Solid organ | Not explicitly mentioned. | X | 184 | 0 | |

CVD, coronary vascular disease; Hx, history

Patients treated: these are the lower estimates of the number of patients treated, as we summed up the lowest number of the frequency intervals (e.g. 1–4 patients were counted as 1).

Major problems=the percentage of physicians respondents reporting they had experienced major problems on giving SCIT to patients with this medical condition. Depending on the condition, N ranges from 93 – physician respondents with experience in patients with bone marrow transplantation – to 639 – physician respondents with experience in patients with hypertension. For the definition of a major problem, see text.

In coordination with the International Societies Council of the European Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (EAACI) a group of investigators is evaluating the quality of AIT guidelines around the globe at this moment, using the AGREE II tool. Preliminary data show the quality of the guidelines varies considerably. In general, the domains 2 (stakeholder involvement) and 5 (applicability) are still the lowest scoring domains, although domain 3 (Scientific rigor) is also not optimal. Another striking observation seems to be that there has not been a major improvement in guideline quality as analyzed with AGREE II, pre- and post-2010, the year of the AGREE II publication. This indicates there is still a lot of room for improvement in this area. Especially enhancing areas 2 and 5 from the very start of a guideline development might possibly help to improve its dissemination and thus augment the number of patients that might benefit from allergen immunotherapy.

Conflict of interestDr. Larenas-Linnemann reports grants and personal fees from Astrazeneca, Boehringer-ingelheim, MEDA, Novartis, grants and personal fees from Sanofi, UCB, GSK, Pfizer, MSD, grants from Chiesi, TEVA, personal fees from Grunenthal, Amstrong, Stallergenes, ALK-Abelló, personal fees from DBV, outside the submitted work; and Chair immunotherapy committee CMICAÐember immunotherapy committee or interest group EAACI, WAO, SLAAIÛoard of Directors CMICA 2018–2019, and Program Chair.