Obstructive respiratory disorders, such as allergic rhinitis and asthma may impair sleep quality. The aim of this study is to validate the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) for Greek children from 6 to 14 years of age. No validated tool has been developed so far to assess sleep disturbances in Greek school-aged children.

MethodsWe examined the reliability and validity of the CSHQ in a sample of children with allergic rhinitis (AR) and a non-clinical population of parents of these children as a proxy measure of children's AR quality of life (QoL) as evaluated by the Pediatric Allergic Rhinitis Quality of Life (PedARQoL) questionnaire.

ResultsThe CSHQ questionnaire Child's Form (CF) had a moderate internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha 0.671 and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.563 when correlated with the PedARQoL (CF). There was also a moderate intraclass correlation of ICC=0.505 between the responses to both questionnaires in the two visits. The CSHQ Parent's Form (PF) had a very good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.928 and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.798. There was a high intraclass correlation of 0.643 between the responses in the two visits.

ConclusionsThe Greek version of the CSHQ CF, but particularly the PF has proved to be a very reliable clinical instrument, which can be used in clinical trials for assessing sleep quality in school-aged children with sleep disturbances because of obstructive airway disorders, such as AR.

Chronic respiratory diseases, such as allergic rhinitis and asthma may impair sleep quality. A common complaint of patients who suffer from rhinitis is impaired daytime performance (including daytime sleepiness) often attributed to impaired sleep. Poor sleep related to allergic rhinitis is not clearly understood but may be in part attributed to nasal congestion.1 Allergic rhinitis (AR) represents a risk factor for snoring in children.2,3 Sleep disturbances and sleep loss may be a result of poorly controlled symptoms. As a result, daytime fatigue leads to decreased overall cognitive function.4,5 Despite a normal night's sleep, fatigue in awakening has a prevalence of 43.7% among allergic rhinitis patients as reported by Leger et al.6 In patients with asthma, the coexistence of perennial non-infectious rhinitis has been shown to be an important risk factor for daytime sleepiness, for difficulty in maintaining sleep and early morning awakening.7 The aim of this study was to examine the reliability and validity of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ)8 in a sample of 112 children suffering from AR and a non-clinical population of parents of these children as a proxy measure of children's AR quality of life (QoL) evaluated by the Pediatric Allergic Rhinitis Quality of Life (PedARQoL) Questionnaire.9

MethodsEthical approval for the clinical study was provided by the Ethics Committee of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. The study was undertaken in the Paediatric Allergy Unit at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. All participants gave informed consent to take part. Both patients and patients’ parents preserved their anonymity when answering the questions.

Patient and parent sampleThe patient sample consisted of one hundred and twelve children in total (75 boys and 37 girls) with a mean age 10.36±2.25 years (range 6–14 yrs). All the participating patients had to meet the inclusion criteria, which were a clinical diagnosis of persistent AR, i.e. having symptoms more than four days per week and for more than four weeks. The patients were ascertained sensitive to a variety of aeroallergens, such as house dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae), grass pollen (Timothy grass, Rye grass, Cynodon dactylon, Meadow fescue), tree pollen (Pinus silvestris, Olive, Cypressus, Platanus), mould (Aspergillus fumigatus, Alternaria alternate) and weed pollen (Parietaria judaica, Parietaria officinalis, Ambrosia artemisiifolia). The diagnosis of AR was based on personal and family medical history, physical examination and positive skin tests to one or more of the previously mentioned aeroallergens. The coexistence of asthma was not an exclusion criterion if the patients had achieved a good control of asthma symptoms in the previous six months. The non-clinical sample were the parents of the participating children with diagnosed AR.9

MaterialsThe Parent's Form (PF) of the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) is a retrospective 45-item questionnaire designed for school-aged children between four and 10 years of age and has been used in several studies to detect sleep behavioural disorders in young children.10–12 The 45 questions were categorised into seven subclasses reflecting the following sleep related disorders: (1) Sleep Onset Delay, (2) Sleep Duration, (3) Bedtime Resistance, (4) Sleep Anxiety, (5) Parasomnias, (6) Night Wakings, (7) Daytime Sleepiness. Children's parents were asked to report sleep disorders which occurred over a “common” recent week. The answers were scored on a three-point scale: “rarely” for a sleep behaviour, which happens from zero to once a week, “sometimes” for two to four times a week and “usually” for a sleep behaviour occurring five to seven times a week.

The Child's Sleep Habit Questionnaire Child's Form (CF) has 26 questions, which are categorised into the following three subclasses: (1) Sleep Duration and Anxiety, (2) Sleep Onset Delay and Bedtime Resistance, (3) Daytime Sleepiness. The answers were scored similarly to the CSHQ (PF).

The Pediatric Allergic Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (PedARhQoL) Child's Form (CF) consists of 20 questions, which were categorised into five health domains, i.e. AR symptoms, symptom duration, emotions, sleep quality and various aspects associated with the experience regarding the management and the life burden related to AR. Answers were scored on a four-point scale (frequently=3, sometimes=2, rarely=1, never=0). Children were asked how much they had been distressed by the AR symptoms and they were also asked to assign symptom duration (a) < than 4h: 3, (b) between 1 and 4h: 2, (c) < than an hour: 1, (d) none: 0. Based on the validation study of the PedARQoL patient's answers yielded a score ranging from 20 to 80 with the lower scores indicating a better QoL.9

Children's parents were asked to complete the PedARhQoL Parent Form (PF). Questions addressed to the participating parents aimed to detect their perception regarding the burden on their child's QoL due to AR. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions which were addressed to the parents of children suffering from AR, i.e. “how much has your child been distressed by the following symptoms”.9

ProcedureThe study was undertaken over a seven-year period from October 2012 to September 2016 at the Pediatric Allergy Unit of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. Participating children and their parents were asked to complete the PedARQoL questionnaire and the CSHQ at two-time points, i.e. before and after topical treatment with fluticasone propionate.

Data analysisData analysis was conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Inc. Armonk, NY). All tests were two-tailed with a significance level set at alpha=0.05. Reliability analysis was applied to the PedRhQoL and the Disabkids Pediatric QoL questionnaire. Internal consistency was assessed by the Cronbach's alpha coefficient and the Guttman split-half coefficient. Pearson's bivariate correlations were calculated between scores measured on a continuous scale to assess convergent validity. Intraclass correlations were calculated to assess the temporal stability of the scale. Following Cohen's conventions13 to interpret effect sizes for correlations, we expected moderate convergent validity correlations of >0.3 with subscales measuring similar aspects of the scale, including the effects regarding patient's time, emotions, activities and general health. Between subjects, t tests were performed to assess the discriminative validity of PedARhQoL and the PedARhQoL PF, by comparing AR demographic characteristics.

ResultsPatient sampleReliability and consistency over time of the Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ)The CSHQ had a moderate internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.480 (which was increased to 0.671 if questions 6, 8, 11, 17 and 26 were dropped out) and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.563 at visit one (V1) and a moderate internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.391 (which was increased to 0.661 if questions 6, 8, 11 and 26 were dropped out) and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.279 at visit two (V2). Cronbach's alpha was 0.462 for Bed Time (if questions 6, 8 and 11 were dropped out), 0.555 for Sleep Disorders (if question 17 was dropped out) and 0.279 for Daytime Sleepiness (if question 26 was dropped out) at V1 and 0.462 for Bed Time (if questions 6, 8 and 11 were dropped out), 0.557 for Sleep Disorders (if question 17 was dropped out) and 0.280 for Daytime Sleepiness (if question 26 was dropped out) at V2.

There was a moderate intraclass correlation between the answers of both questionnaires in the two visits (ICC=0.505). ICC was 0.372 for Bed Time, 0.640 for Sleep Disorders and 0.373 for Daytime Sleepiness.

There was a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of the two questionnaires at V1 (mean=56.48±SD=5.06) and V2 (mean=57.76±SD=4.42), (t (113)=−2.892, p=0.005). Regarding the three subscales of CSHQ, Bed Time mean score remained unchanged (25.59±2.58 at V1 vs. 25.94±2.20 at V2; t (113)=−1.392, p=0.167). Statistically significant differences were observed for Sleep Disorders (17.72±2.39 at V1 vs. 18.22±2.27 at V2; t (113)=−2.698, p=0.008) and Daytime Sleepiness (8.32±1.59 at V1 vs. 8.65±1.33 at V2; t (113)=−2.165, p=0.032).

Discriminative validityThere was a weak positive correlation of the CSHQ scores with children's age at visit one (Pearson's r=0.260, p=0.004) and visit two (Pearson's r=0.211, p=0.029). There was a tendency towards higher CSHQ scores in boys, which did not reach statistical significance (V1: 57.04±5.11 in boys vs. 55.42±4.68 in girls, t (121)=1.725, p=0.087; V2: 58.26±4.29 in boys vs. 56.83±4.60 in girls, t (111)=1.666, p=0.098).

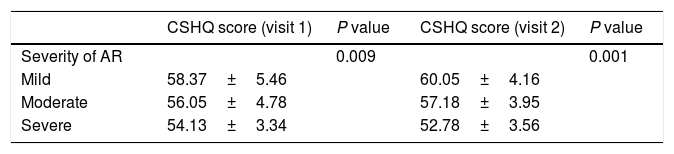

Correlation with expert's opinionOne-way ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in the mean CSHQ scores according to the doctor's opinion on disease severity at the two visits (V1: F (2, 121)=4.859, p=0.009; V2: F (2,111)=13.858, p<0.001; Table 1). Post hoc analysis using Tukey's test showed that children with mild disease presented a higher score compared to children with moderate (p=0.055) and severe (p=0.012) disease at V1; there was no statistically significant difference between children with moderate and severe disease (p=0.321). At V2, children with mild disease presented higher scores compared to children with moderate (p=0.002) or more severe disease (p<0.001). Children with moderate disease presented higher scores, statistically significant, in comparison to children with severe disease (p=0.007).

Parent sampleReliability of the CSHQ PFThe CSHQ PF had a very good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.928 and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.856 at V1 and a very good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.920 and Guttman split-half coefficient of 0.798 at V2. Cronbach's alpha was 0.835 for Sleep Habits, 0.872 for Night-time Sleep Behaviour, 0.532 for Awakening during Sleep, 0.773 for Morning Awakening and 0.519 for Daytime Sleepiness at V1 and 0.844 for Sleep Habits, 0.877 for Night-time Sleep Behaviour, 0.432 for Awakening during Sleep, 0.777 for Morning Awakening and 0.483 for Daytime Sleepiness at V2.

There was a high intraclass correlation between the responses to both questionnaires in the two visits (ICC=0.643). ICC was 0.594 for Sleep Habits, 0.575 for Night-time Sleep Behaviour, 0.284 for Awakening during Sleep, 0.674 for Morning Awakening and 0.456 for Daytime Sleepiness.

There was a difference between the mean scores of the two questionnaires at V1 (mean=178.67±SD=29.36) and V2 (mean=182.64±SD=26.86) of marginal significance (t (113)=−1.784, p=0.077). Regarding the five subscales of CSHQ PF, a statistically significant change was observed in Night-time Sleep Behaviour scores (78.47±13.21 at V1 vs. 81.11±12.67 at V2; t (113)=−2.354, p=0.020) but not in Sleep Habits (43.00±9.53 at V1 vs. 43.60±9.79 at V2; t (113)=−0.732, p=0.466), Awakening during Sleep (11.42±2.52 at V1 vs. 11.79±2.27 at V2; t (113)=−1.372, p=0.173), Morning Awakening (29.36±6.85 at V1 vs. 29.61±6.57 at V2; t (113)=−0.484, p=0.629) and Daytime Sleepiness (16.41±2.42 at V1 vs. 16.54±2.24 at V2; t (113)=−0.578, p=0.564).

Discriminative validityThere was no correlation of the CSHQ PF scores with children's age at visit one (Pearson's r=0.155, p=0.093) and visit two (Pearson's r=0.076, p=0.434). There was no statistically significant difference between boys and girls in CSHQ PF scores at V1 (180.34±28.01 in boys vs. 176.26±30.44 in girls, t (121)=0.747, p=0.456). Statistically significantly higher CSHQ PF scores were found in boys at V2 in comparison to girls (187.42±26.41 vs. 174.39±26.23 respectively, t (111)=2.527, p=0.013).

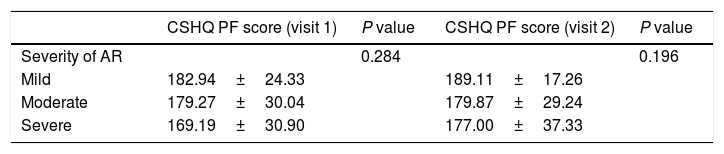

Correlation with expert's opinionOne-way ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences in the mean CSHQ PF scores based on doctor's opinion about the severity of the disease at the two visits (V1: F (2,121)=1.272, p=0.284; V2: F (2,111)=1.653, p=0.196; Table 2).

Association of the CSHQ scores (PF) with the expert's perception of disease severity before and after treatment.

| CSHQ PF score (visit 1) | P value | CSHQ PF score (visit 2) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of AR | 0.284 | 0.196 | ||

| Mild | 182.94±24.33 | 189.11±17.26 | ||

| Moderate | 179.27±30.04 | 179.87±29.24 | ||

| Severe | 169.19±30.90 | 177.00±37.33 |

The main findings of this study were a moderate association between children's responses to the PedARhQoL (CF) and the CSHQ (CF) and a good association between parent's responses registered in the relative (PF)s of the previous questionnaires.

A shortened version of the CSHQ (CF) had a moderate internal consistency when correlated with the PedARhQoL (CF) before and after treatment for the domains of Bed Time, Daytime Sleepiness and Sleep Disorders. The intraclass correlation between the responses of both questionnaires in the two visits was also moderate. The mean scores of the two questionnaires at the two time-points were statistically significant. Regarding the three subscales, the Bed Time mean score did not change, but Sleep Disorders and Daytime Sleepiness had statistically significant differences.

The CSHQ (CF) score did not correlate with children's age, i.e. children did not report a better or worse sleep quality based on their age. However, boys tended to report worse sleep quality in relation to girls, with no statistical significance.

The CSHQ (CF) scores correlated moderately well with the expert's opinion regarding the severity of the disease. Children with mild disease revealed higher scores indicative of a better sleep quality. However, the CSHQ (CF) scores could not discriminate children with moderate and severe disease based on the expert's opinion about the severity of the disease, as no statistically significant difference was found between the previous two groups. At V2, the CSHQ (CF) scores were well correlated with the expert's opinion for mild, moderate and severe disease.

The CSHQ (PF) had a very good internal consistency when correlated with the PedARhQoL (PF) before and after treatment for the whole questionnaire. There was a very good internal consistency for the domain of Sleep Habits, Night-time Sleep Behaviour and Morning Awakening. There was a moderate internal consistency for the Awakening during Sleep. A high intraclass correlation between the two questionnaires was obtained at the two time-points. The better correlation observed between the parent's responses compared to children's responses could possibly be attributed to the fact that parents were more reliable observers of obstructive sleep disorders, such as sleeping with an open mouth, or snoring, while the children's perception of impaired sleep was underestimated as they were not aware while they were sleeping.

At V1, parents did not recall any difference in children's sleep quality, in relation to their age and sex. Nevertheless, at V2, parents’ impression was that boys in comparison to girls had worse sleep quality and in a statistically significant manner.

The CSHQ (PF) scores did not correlate with the expert's opinion about the severity of the disease. A possible explanation for the lack of association between expert's opinion regarding the AR severity and the relative burden on sleep quality could possibly be that the expert rated the AR as severe when sleep was disrupted due to AR symptoms during the night resulting in sleep loss, while the CSHQ reflected a poor sleep quality, not simply as a part of disrupted sleep during the night, but also as a result of anxiety and/or other psychiatric disorders, which was a significant component of the CSHQ(PF) questionnaire.

A limitation of this study is that the comparison of the CSHQ (CF) and (PF) was done with the PedARQoL, which is an instrument that does not directly measure the sleep quality. Although the PedARQoL (CF) and (PF) measures the burden of QoL in children with AR symptoms, it contains a section of questions assessing sleep, so the overall QoL score is affected by the burden of a poor sleep quality. Moreover, the AR symptoms affecting sleep cause hindering of the daily functioning as assessed by the PedARQoL. Thus, one would expect a poor quality of sleep assessed by the CSHQ to be associated with a poor QoL assessed by the PedARQoL. Currently, there is no other valid scale or instrument in Greece to assess the quality of sleep.

In summary, the CSHQ (CF) had a moderate internal consistency and intraclass correlation, but particularly the CSHQ (PF) had a very good internal consistency and a high intraclass correlation when compared with the PedARhQoL. In conclusion, the CSHQ and especially the PF, has proven to be a very reliable tool for assessing sleep disorders in children with chronic obstructive respiratory diseases, such as AR.

Conflict of interestNone.

Registration No: No clinical registration number is provided for this clinical trial as no experimental pharmaceutical agents have been used. The study was conducted by means of questionnaires and the treatment followed is a well-established conventional treatment for allergic rhinitis.