Common variable immune deficiency (CVID) is a heterogeneous syndrome with a wide variety of signs and symptoms. This study describes the phenotyping and survival of the CVID patients in the allergy and clinical immunology department of Rasol-E-Akram Hospital of Iran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran.

MethodWe retrospectively reviewed hospital files of CVID patients in our department until January 2014. All patients were diagnosed with standard diagnostic criteria of CVID, treated and visited monthly, during the follow-up period. We divided the patients into four phenotypes; infection only, cytopenia, polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration and unexplained enteropathy. The immunologic, demographic and clinical findings in different phenotypes were analysed.

ResultsThe study included 47 CVID patients with mean age at onset of symptoms and diagnosis of 11.2 and 20.2 years, respectively. Phenotyping of our patients was: only infection (62%), cytopenia (26%) and PLI (19%) and 94% of cases had only one phenotype. We did not find a significant relation between the clinical phenotypes and immunologic or demographic data. Rate of parental consanguinity in our cases was 47%. Parental consanguinity was related to lower age at onset, lower age at diagnosis and higher baseline IgG levels. Patients with malignancy and autoimmunity had significantly higher age at onset. Our patients were followed-up for 6.9 years and the mortality rate during this time was 6%.

ConclusionsParental consanguinity and age at onset of CVID symptoms may have important roles in CVID manifestations.

Common variable immune deficiency (CVID) is a heterogeneous syndrome characterised by hypogammaglobulinaemia, recurrent infections, immune dysregularity and propensity to malignancies.1–6 The first case of CVID was reported in 1953 by Janeway C.A.7 Today it is the most common symptomatic primary immune deficiency and its prevalence is 1 in 25,000 to 50,000 in general populations.8,9 The most common infectious manifestations of CVID are sinopulmonary and gastrointestinal infections.8,9 On the other hand more than 25% of CVID patients have autoimmune or auto-inflammatory complications.3,10,11 The only available treatment for CVID is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) and appropriate management of its complications.12,13 The mortality rate for CVID patients has been estimated to be 6% in 11.5 years and 20% in about four decades in western countries.3,9 The purpose of this study is to classify a group of Iranian CVID patients according to the clinical phenotypes defined by Chapel et al. for European patients,14 and to determine the relationship between these phenotypes and morbidity, mortality, complications, age at onset of the disease and parental consanguinity.

MethodsThe Allergy and Clinical Immunology department of Rasol E Akram Hospital of Iran University of Medical sciences, Tehran, Iran is a referral department for primary immune deficient patients of all ages. We retrospectively reviewed hospital files of the immunology clinic of this department until January 2014 and found 47 CVID patients who were diagnosed according to PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiency) diagnostic criteria.15,16 Patients are diagnosed as CVID when at least four years old, to exclude transient hypogammaglobulinaemia of infancy. Genetic testing to exclude autosomal recessive and X-linked agammaglobulinaemia and hyper IgM syndromes was done as a part of genetic consultation with the Research Center for Immunodeficiencies in the Children's Medical Center of Tehran University of Medical Sciences; cases with known monogenic defect were excluded from the cohort. These patients are being visited at least monthly and treated with IVIG and antibiotics as needed. According to their Clinical and paraclinical data and based on criteria described by Chapel et al.,14,17 we divided the patients into four phenotypes including; infection only (with no complication other than infections); cytopenia (thrombocytopenia, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia or neutropenia); polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration (granuloma, persistent unexplained lymphadenopathy or lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis (LIP); and unexplained enteropathy (enteropathy insensitive to gluten withdrawal). Information on overlapping phenotypes was also recorded.

Statistical analysis was carried out using STATA 10 software. Quantitative data were reported as mean and range and descriptive variables as proportion. T-test and analysis of variances (ANOVA) were used to compare means and chi-square test was used to compare proportions. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as significant.

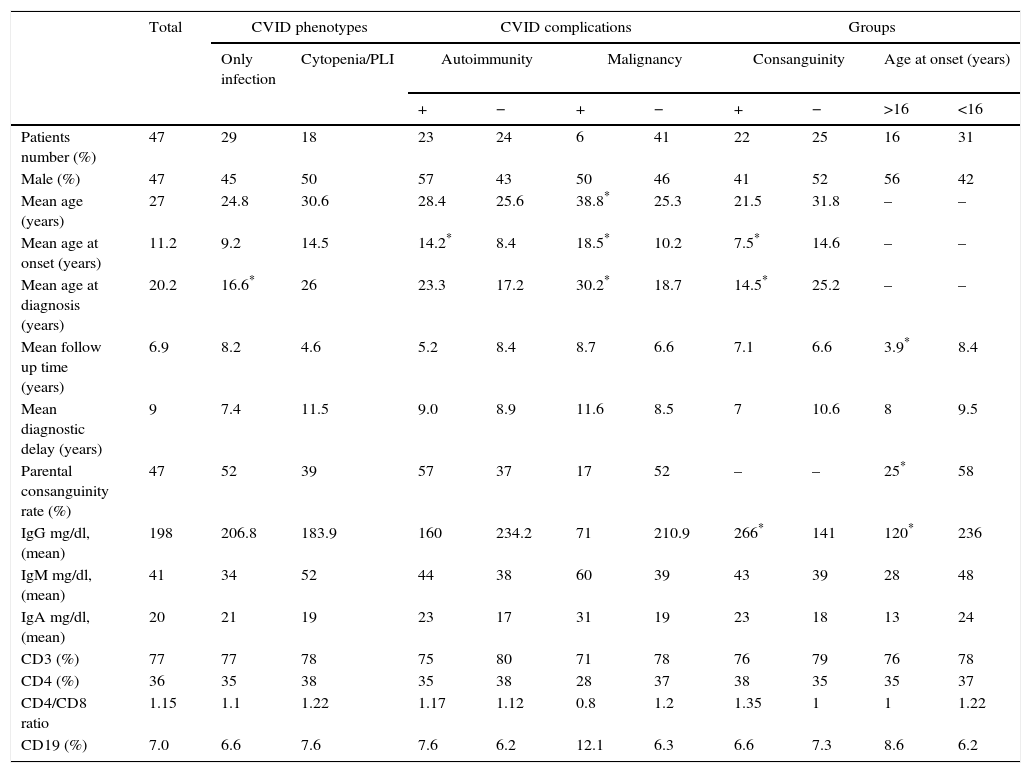

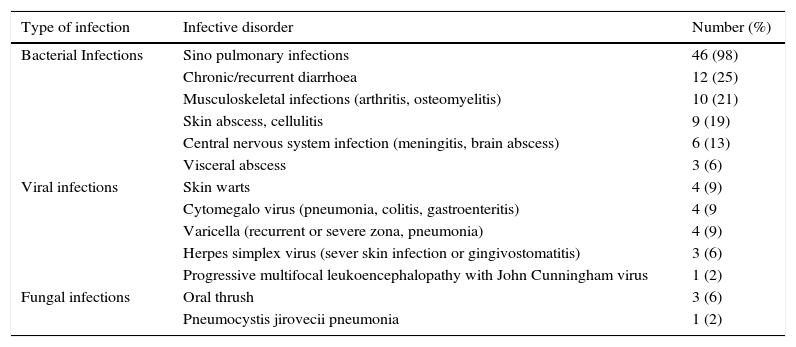

ResultsCharacteristics of patientsOur study included 47 CVID patients with a mean age of 27 years (range: 4–63) and mean follow-up time of 6.8 years (range: 0.5–23). The mean age of onset of CVID symptoms was 11.2 years (range: 1–32). Table 1 includes demographic and immunologic data, phenotypes and complications of the patients. Phenotyping of our patients was: only infection (62%), cytopenia (26%) and PLI (19%) with no case in the unexplained enteropathy group. 94% of our cases had only one phenotype. We compared immunologic and demographic data between the patients with the infection only phenotype and other phenotypes all together and found no significant difference, except the rate of splenomegaly which was significantly lower in the infection only phenotype (10% vs. 71% P value=0.00001). In 85% of patients the first sign of immunodeficiency was infections, while autoimmune or auto-inflammatory manifestations were the first sign in the other 15%. Sino pulmonary infections were the most common infection of our CVID patients (98%) (Table 2). Twenty patients (43%) complained from chronic/recurrent diarrhoea; among them, eight cases were diagnosed to have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), five had recurrent bacterial gastroenteritis, two had cytomegalovirus enterocolitis, one had chronic resistant giardiasis, while in four patients, recurrent diarrhoea without endoscopic and pathologic signs of IBD or enteropathy persists with no identifiable germ that responds partially to antibiotic therapy.

Demographic and immunologic data of 47 Iranian CVID patients.

| Total | CVID phenotypes | CVID complications | Groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only infection | Cytopenia/PLI | Autoimmunity | Malignancy | Consanguinity | Age at onset (years) | ||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | >16 | <16 | ||||

| Patients number (%) | 47 | 29 | 18 | 23 | 24 | 6 | 41 | 22 | 25 | 16 | 31 |

| Male (%) | 47 | 45 | 50 | 57 | 43 | 50 | 46 | 41 | 52 | 56 | 42 |

| Mean age (years) | 27 | 24.8 | 30.6 | 28.4 | 25.6 | 38.8* | 25.3 | 21.5 | 31.8 | – | – |

| Mean age at onset (years) | 11.2 | 9.2 | 14.5 | 14.2* | 8.4 | 18.5* | 10.2 | 7.5* | 14.6 | – | – |

| Mean age at diagnosis (years) | 20.2 | 16.6* | 26 | 23.3 | 17.2 | 30.2* | 18.7 | 14.5* | 25.2 | – | – |

| Mean follow up time (years) | 6.9 | 8.2 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 3.9* | 8.4 |

| Mean diagnostic delay (years) | 9 | 7.4 | 11.5 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 8.5 | 7 | 10.6 | 8 | 9.5 |

| Parental consanguinity rate (%) | 47 | 52 | 39 | 57 | 37 | 17 | 52 | – | – | 25* | 58 |

| IgG mg/dl, (mean) | 198 | 206.8 | 183.9 | 160 | 234.2 | 71 | 210.9 | 266* | 141 | 120* | 236 |

| IgM mg/dl, (mean) | 41 | 34 | 52 | 44 | 38 | 60 | 39 | 43 | 39 | 28 | 48 |

| IgA mg/dl, (mean) | 20 | 21 | 19 | 23 | 17 | 31 | 19 | 23 | 18 | 13 | 24 |

| CD3 (%) | 77 | 77 | 78 | 75 | 80 | 71 | 78 | 76 | 79 | 76 | 78 |

| CD4 (%) | 36 | 35 | 38 | 35 | 38 | 28 | 37 | 38 | 35 | 35 | 37 |

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 1.15 | 1.1 | 1.22 | 1.17 | 1.12 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.35 | 1 | 1 | 1.22 |

| CD19 (%) | 7.0 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 12.1 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 8.6 | 6.2 |

Infective disorders in 47 Iranian CVID patients.

| Type of infection | Infective disorder | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Infections | Sino pulmonary infections | 46 (98) |

| Chronic/recurrent diarrhoea | 12 (25) | |

| Musculoskeletal infections (arthritis, osteomyelitis) | 10 (21) | |

| Skin abscess, cellulitis | 9 (19) | |

| Central nervous system infection (meningitis, brain abscess) | 6 (13) | |

| Visceral abscess | 3 (6) | |

| Viral infections | Skin warts | 4 (9) |

| Cytomegalo virus (pneumonia, colitis, gastroenteritis) | 4 (9 | |

| Varicella (recurrent or severe zona, pneumonia) | 4 (9) | |

| Herpes simplex virus (sever skin infection or gingivostomatitis) | 3 (6) | |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with John Cunningham virus | 1 (2) | |

| Fungal infections | Oral thrush | 3 (6) |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | 1 (2) |

Four patients with a mean age at onset of 17 years had history of chronic wart; among them two had IBD, one had recurrent diarrhoea and none of them had neutropenia. Three patients with a mean age at onset of nine years and no lymphopenia had history of oral thrush; among them one developed leukaemia, one had history of CMV pneumonia and LIP and one had history of recurrent pneumonia and warts since 20 years of age who died because of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with John Cunningham virus at 30 years old.

Parental consanguinityPatients with parental consanguinity had significantly lower age of onset of CVID symptoms (7.5 vs. 14.6 yrs, P value=0.01), lower age of diagnosis (14.5 vs. 25.2 yrs, P value=0.002) and higher baseline IgG level (266 vs. 141mg/dl P value=0.01). Other clinical and immunological data were not significantly different.

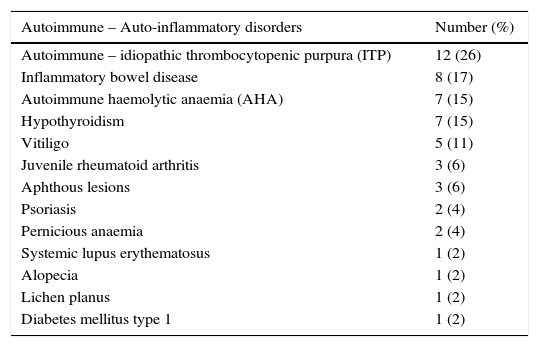

AutoimmunityAutoimmunity was detected in 23 cases (49%) and 12 of them had more than one autoimmune disorder. Autoimmunity was the first manifestation of CVID in seven patients, but in six cases it was occurring during five years, in four cases in a period of 5–10 years and in six cases 10 years after CVID onset. Fifty seven percent of patients with autoimmunity have parental consanguinity vs. 37% in the others, which was not significant (P value=0.19). The most common autoimmunity was idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) which was detected in 12 (26%) cases (Table 3). Three cases underwent splenectomy to treat ITP; two of them had this procedure before CVID diagnosis. IVIG replacement in routine doses for treatment of hypogammaglobulinaemia in CVID did not modify the pattern or recurrence of autoimmune disorders significantly.

Autoimmune and auto-inflammatory disorders in 47 Iranian CVID patients.

| Autoimmune – Auto-inflammatory disorders | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune – idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) | 12 (26) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 8 (17) |

| Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (AHA) | 7 (15) |

| Hypothyroidism | 7 (15) |

| Vitiligo | 5 (11) |

| Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (6) |

| Aphthous lesions | 3 (6) |

| Psoriasis | 2 (4) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 2 (4) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 (2) |

| Alopecia | 1 (2) |

| Lichen planus | 1 (2) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | 1 (2) |

The mean age of onset of CVID symptoms in cases with autoimmune manifestations was 14.2 years vs. 8.4 years in others (P value=0.03) and 48% of them had an age of onset of >16 years vs. 21% of cases without autoimmunity (P value=0.05).

IBD was diagnosed in eight (17%) cases, from which 62% also had other autoimmune disorders. The diagnosis of IBD was made according to clinical manifestations, endoscopic view, and pathological findings. In all these cases, IBD was diagnosed prior to the CVID. All the patients were treated with local and systemic anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs successfully. Of IBD cases one died because of severe hepatic failure and two cases developed malignancy in the course of disease.

MalignanciesMalignancy occurred in the follow up of six patients (13%). One patient had two different malignancies; breast cancer at 55 years old and gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma at 63 years old. Malignancy risk per case was 15%. Malignancies occurred in a period of 3–33 years after onset of CVID (mean of 17.4 years). Hodgkin's lymphoma was the most common malignancy (three cases, 6%). Other malignancies included: breast cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, leukaemia, and brain cancer. The mean age at onset and age at diagnosis of CVID in patients with malignancy was significantly higher than CVID cases without malignancy (18.5 and 38.8 vs. 10.2 and 18.7 years, respectively) (P values=0.04 and 0.03, respectively). Splenomegaly (years before the onset of malignancy) was more common in CVID cases with malignancy than the others (83% vs. 25%) (P value=0.004) (Table 1).

Age at onset of CVID symptomsAccording to the age of onset, patients were divided into two groups; 31 cases below and 16 cases above 16 years. Patients with age of onset of less than 16 years had higher baseline IgG level (236 vs. 120mg/dl, P value=0.027) and higher consanguinity prevalence (58% vs. 25%, P value=0.03). Other differences in clinical and immunologic data were not significant.

MortalityDuring the follow up period, three cases (6%) died. Causes of death were malignancy, hepatic failure and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Mean age of onset, follow up time and age at death in these cases were 24, 4, and 36 years, respectively.

DiscussionThis study showed that the mean age of onset of CVID symptoms is about 11.2 years, while this was reported to be lower than three years in most previous reports from other centres in Iran.2,18–21 In Western countries the CVID symptoms usually begin in the second and third decades of life.3,9,17 It was hypothesized that this difference may be due to the high rate of parental consanguinity in Iranian CVID cases (72%),21 compared to Western countries. In the French DEFI (deficits immunitaires) study the rate of parental consanguinity in CVID patients was 5.5% and there was no relationship between age of onset and parental consanguinity.22 In this study, age at onset and age at diagnosis of CVID were significantly lower in cases with parental consanguinity. Our department is built in a general hospital that is a referral centre for children and adult CVID patients and in addition to lower rate of parental consanguinity (47% vs. 72%), this can be another explanation of the higher age of onset compared to other centres that are in children's hospitals.

Clinical phenotypes and the severity of CVID has been shown to be related to parental consanguinity in some registries21,22 but in our study there is no relationship between CVID phenotypes or complications such as autoimmunity or malignancy and parental consanguinity.

This study showed that higher age of onset of CVID is significantly associated with the higher risk of malignancy, which has been shown in previous studies.23 We also found significant association between these variable and autoimmune disorders.

As in other studies,11,24,25 infections are the first manifestation in most (85%) of our CVID cases and autoimmune or auto-inflammatory manifestations are the first sign in the rest of the cases. Sino pulmonary and gastrointestinal infections were the most common infections in our study, but 25% of patients had problematic viral infections which can be due to associated abnormalities in T cell and innate immunity.26–28

Autoimmunity has been reported in about 20–25% of CVID patients.11,29 In an Iranian report in a children's medical centre, 11% of CVID patients had autoimmunity21 and the autoimmunity rate was not associated with parental consanguinity and age at onset. In this study, 49% of CVID cases had autoimmunity, and ITP was the most common type. The age at onset was significantly higher in CVID cases with autoimmunity, with no significant difference in parental consanguinity rate.

Malignancies has been reported in 2.5–8% of CVID patients23 and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is the most common type in most reports.1,23,30 In our study, 13% of patients are complicated with malignancy and Hodgkin's lymphoma was the most common. In another study from Tehran Children Medical Center, the malignancy rate in CVID patients was 10% after 5.2 years follow up and Hodgkin's lymphoma was the most common.2 Age at onset of CVID symptoms was significantly higher in cases with malignancy with no significant difference in consanguinity rate.

We found no association between parental consanguinity, IgG, IgM, IgA, CD4 and CD8 levels with clinical phenotypes while previous studies have shown significant associations.14,17,21,22

An Iranian study in 2007 reported 35% mortality during 6.5 years post diagnosis,31 while in our study 6% of patients died in 6.8 years follow up period. The lower mortality rate in our study can be related to greater availability of IVIG drugs, supportive care and early diagnosis of disease due to increased overall awareness of physicians and patients.

Higher age at onset and probable genotypic differences in our population of CVID in comparison to the Children's Medical Center can be another reason for the difference in the mortality rate.

ConclusionsAge at onset of CVID symptoms and parental consanguinity may have an important role in CVID manifestations. The survival rate of CVID patients has been improved in recent years due to socioeconomic improvements.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.