Lichens are composite organisms consisting of the permanent association between a fungus and an alga. The fungus component is called mycobiont and the algal component is called phycobiont; both grow in a symbiotic relationship1, usnic acid is one of their main components and it is found in different types of lichens.2 In Portugal, there are four predominant species of lichens: Parmelia reticulata, P. caperata, Ramalina lusitana, and R. usnea, which grow mainly on olive trees.3,4 Airborne allergic contact dermatitis (AACD) caused by lichens4,5 may simulate photodermatitis due to its preferential location in exposed areas of the skin. In rural workers, AACD may appear in the context of an occupational dermatitis, which is sometimes disabling, or it may affect those involved in outdoor leisure activities.5

Herein, we described the case of a 46-year-old Caucasian woman, rural domestic worker, who carried oak and olive wood for fireplaces, mainly between the months of October and March.

The patient was referred to the dermatology department because of an intensely pruritic erythematous scaling dermatitis, involving the face, neckline, and extensor surface of the hands, forearms and lower limbs. On the face, the eyelids, earlobes, and retroauricular fold were affected. The extensor surface of the forearms and hands showed extensive lichenification (Fig. 1). The dermatitis had started in the autumn, and persisted throughout the winter, with worsening on the uncovered areas in the beginning of the spring.

The patient had a history of asthmatic bronchitis and allergic rhinitis in childhood and had been followed for her respiratory allergies since 1993. Her most recent laboratory investigations showed: D2-Dermatophagoides farinae specific IgE 90.10kU/L (class 5); D1 D. pteronyssinus specific IgE>100kU/L (class 6), and total Ig E 1977U/mL (ref<87).

The patient underwent patch testing with the Basic Series adopted by the GPEDC (Grupo Português das Dermites de Contacto), and the Gloves and Clothing Series, all of which were negative.

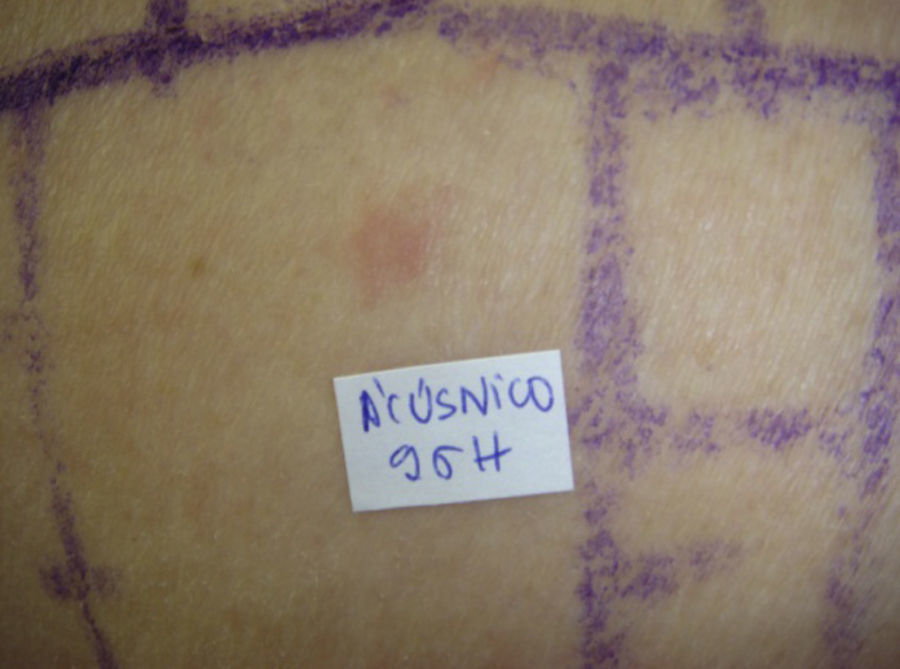

Faced with the possibility of photodermatitis, the patient performed tests with the Photo Allergen Series, which showed the following positivities: lichen acid mix and usnic acid, after UVA irradiation with 5J/cm2 (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Patients with lichen allergies may be photosensitive and score positively on photoepicutaneous tests. The clinical relevance of this phenomenon is yet to be established.4 Our patient was a rural worker who carried oak and olive wood during the cold months, and who developed dermatitis of sun-exposed areas, with accentuated lichenification of the dorsal hands and forearms, which worsened with exposure to sunlight. When faced with a rash on photo-exposed areas, and outdoor activity, one should always think of photosensitivity or AACD. In this case, the study with the Photo Allergen Series revealed positivity to lichen acid mix and usnic acid, which increased after UVA irradiation, thus confirming the diagnostic hypothesis of AACD.

Immediate hypersensitivity after exposure to lichens has also been described, which is usually manifested through respiratory symptomatology.1 However, even though our patient had a history of respiratory allergies, there is no evidence to support that they occurred in this setting.

Usnic acid is a lichen component which is found in species such as: Parmelias, Evernia, Usnea, Lecanora, Cladonia or Ramalina, and which may be photosensitising (Fig. 3). These types of lichens are epiphytic, i.e. grow on tree trunks, and only a few survive in the polluted air of the cities, contaminated with sulphur dioxide. When lichens are fragmented by handling, they release particles that can settle on the exposed skin and may cause AACD,1 an occupational dermatitis that affects rural workers who cut tree trunks, or individuals with sporadic exposure during outdoor leisure activities.5–7 There may be concomitant reactions with the Frullania family due to cohabitation of both species. The existence of contact dermatitis caused by allergy to the Frullan's sesquiterpene lactones may predispose subjects to being sensitive to lichen chemical compounds.8

Lichen contact allergy is an old and often overlooked dermatitis that should be considered for subjects in contact with barked wood or wood dust. It is important to know the native species from each country to have a certain aetiological factor. In Portugal, several studies have been published in which the main aetiological sources of this type of dermatitis, both occupational and leisure-related, are described.9

Moreover, numerous lichen components, such as usnic acid and atranorin (“oak moss”), are used in perfumery. Nowadays, this is the main cause of sensitisation to this type of substances.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Patients’ data protectionThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.