There are only a few studies regarding the prevalence of atopy in Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) patients, and their results are conflicting.

MethodsIn this study children with the diagnosis of FMF were evaluated for the presence of atopy by comparing with controls. One hundred and eighteen children diagnosed as FMF and 50 healthy age and sex matched controls were enrolled. They were evaluated for the presence of rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, urticaria and asthma. Laboratory assessment was done by measuring IgA, IgM, IgG, IgE levels, total eosinophil count and by performing skin prick test (SPT) panels for common allergens to children with FMF and healthy controls.

ResultsOne hundred and eighteen children (61girls and 57 boys) diagnosed as FMF with a median age of 120±47 months (range 36–204 months) were compared with 50 healthy controls (31 girls and 19 boys) having a median age of 126±37 (range 48–192 months). The mean percentage of total eosinophil count of patients was similar to that of the control group. The mean level of IgE was significantly higher in children with FMF than controls (136±268, 87±201, respectively; p values <0.05). The percentage of skin prick test positivity was similar for both patients and controls (13% and 8.2%, respectively; p>0.05). The prevalences of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in the patient group were 5.08%, 28.8%, and 15.25%, respectively, while the control group had the prevalences of 0%, 36%, and 14% respectively.

ConclusionChildren with FMF did not show an increase of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma with respect to controls.

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autosomal recessive disease which is characterised by recurrent episodes of fever, abdominal pain, chest pain and arthritis. It is accepted to be the prototype of auto-inflammatory diseases.1 In FMF, the MEFV gene mutations cause uncontrolled and persistent inflammation by the influence of protein pyrin. The effect of pyrin is still unclear but there is an agreement of increased processing and production of IL-1β during attacks.2,3 According to the previous studies, Th1 cells were assigned to be the major inflammatory cells at play by promoting actions of macrophages and maintaining inflammatory response.4 But, rather than a simple Th1 influence at the pathophysiology of FMF, a more complex integration of cytokines like IL-6, IL-10, IL17 and TGF-β were suggested.5,6 So besides Th1, more diverse cell populations, in particular TH17 and Tregs, were shown to play a role in FMF.7,8

For a long while, allergic diseases were characterised by dysregulated Th2 responses, but accumulating knowledge suggests a considerable Th17 effect at the immunopathogenesis contributing to inflammation both by increasing inflammatory cell migration and to a lesser extent triggering Th2 directed responses.9

There are few studies showing the low prevalence of atopy in patients with FMF.10,11 But the changing knowledge about the Th1/Th2 paradigm and emergence of new perspectives in the immunopathogenesis of both FMF and allergic diseases led us to hypothesise the idea that as Th17 was playing a common role in both of these diseases, the prevalence of allergic diseases in FMF patients may not be different from the healthy population.

MethodsThe study was approved by the institutional review board and fulfilled the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration (Edinburgh, 2000). Informed parental consent was taken from all the participants before inclusion. The study was planned as a prospective comparative cohort.

The study consisted of 118 children with FMF diagnosed and followed-up by a paediatric rheumatologist at the paediatric rheumatology out-patient clinic of Istanbul Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Education and Research Hospital, Turkey, and 50 age and sex matched healthy controls. Diagnosis of FMF was based on the Tel-Hashomer Criteria.12 All patients were in clinical remission and all were taking colchicine. No patient or control was taking any other drug (especially no antihistaminic medication four weeks before their involvement in the study). Subjects had the results of genetic analysis for the most common FMF mutations in Turkey (M694V, M680I, V726A, E148Q, M694I). Routine screenings done at every visit, like complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A were recorded.

Children with FMF and the controls were referred to the paediatric allergy out-patient clinic. The diagnosis of allergy was made by paediatric allergy specialists. Skin prick tests were applied epicutaneously for Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, tree pollens, grass and cereal pollens, animal danders, moulds, milk, egg yolk and egg white (Allergopharma, Rheinbek, Germany). Histamine was accepted as positive control and saline as negative control. The test was considered positive if the mean wheal diameter was ≥3mm compared with the negative control after 20min. Eosinophil counts were measured using a complete blood cell autoanalyser. IgE levels were measured using nephelometric immunoassay. IgE levels above 100IU/ml and eosinophil counts over 500/μL were regarded as above normal. Overall atopy was defined as the presence of at least one of asthma, allergic rhinitis or eczema.

Symptoms of any allergic disease were assessed using the ISAAC questionnaire form. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) is a standardised questionnaire designed to evaluate the prevalence and severity of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic eczema. It had been previously validated among Turkish children.13,14 In this study, the questionnaires were asked face-to-face to parents of the participants and controls.

Asthma is defined as asthma diagnosed by a doctor or a diagnosis of allergic bronchitis and/or ≥3 bronchitis episodes, and wheezing or whistling in the chest or asthma crisis during the last 12 months. Allergic rhinitis is defined as experiencing problems with sneezing, or having a runny or blocked nose during the last six months without presence of the common cold or flu. Eczema is defined as recurrent erythema, and itching or rash over the body without fever in the last six months. Atopy in the family was defined as a positive history or diagnosis of asthma, rhinitis, and/or eczema in one or both parents.10,13,14

Statistical methodsStatistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 16.0 statistical package. The data were evaluated using descriptive statistical methods (mean±standard deviation, median, frequencies and percentages). Chi-squire test was performed to compare the difference of frequencies of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopy between patients and controls. A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

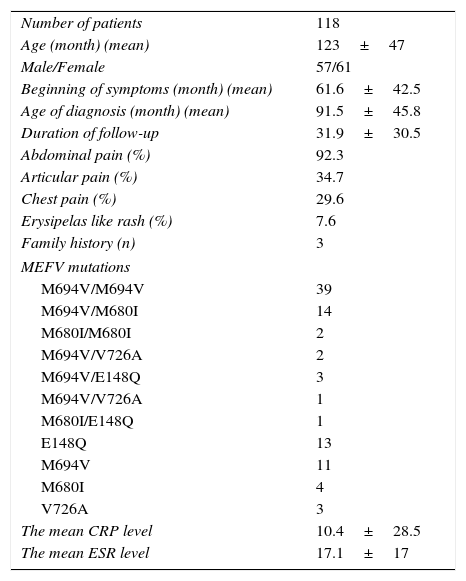

ResultsThis prospective cohort consisted of 118 patients and 50 controls. The median age and gender balance of the patient and control groups were similar (120±47 months, 61 girls and 126±37 months, 31 girls, respectively; both p values >0.05). The demographic data, clinical findings, laboratory results and mutation analysis are shown in Table 1.

Clinical and demographical features with genetic analysis.

| Number of patients | 118 |

| Age (month) (mean) | 123±47 |

| Male/Female | 57/61 |

| Beginning of symptoms (month) (mean) | 61.6±42.5 |

| Age of diagnosis (month) (mean) | 91.5±45.8 |

| Duration of follow-up | 31.9±30.5 |

| Abdominal pain (%) | 92.3 |

| Articular pain (%) | 34.7 |

| Chest pain (%) | 29.6 |

| Erysipelas like rash (%) | 7.6 |

| Family history (n) | 3 |

| MEFV mutations | |

| M694V/M694V | 39 |

| M694V/M680I | 14 |

| M680I/M680I | 2 |

| M694V/V726A | 2 |

| M694V/E148Q | 3 |

| M694V/V726A | 1 |

| M680I/E148Q | 1 |

| E148Q | 13 |

| M694V | 11 |

| M680I | 4 |

| V726A | 3 |

| The mean CRP level | 10.4±28.5 |

| The mean ESR level | 17.1±17 |

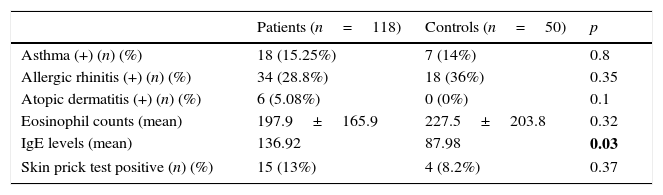

The prevalences of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in the patient group were 5.08%, 28.8%, and 15.25%, respectively, while the control group had the prevalences of 0%, 36%, and 14% respectively. When compared with the control group, the children with FMF had non-significantly increased prevalences of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma. The comparisons are summarised in Table 2.

Characteristic of atopic findings and laboratory features related to allergy.

| Patients (n=118) | Controls (n=50) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma (+) (n) (%) | 18 (15.25%) | 7 (14%) | 0.8 |

| Allergic rhinitis (+) (n) (%) | 34 (28.8%) | 18 (36%) | 0.35 |

| Atopic dermatitis (+) (n) (%) | 6 (5.08%) | 0 (0%) | 0.1 |

| Eosinophil counts (mean) | 197.9±165.9 | 227.5±203.8 | 0.32 |

| IgE levels (mean) | 136.92 | 87.98 | 0.03 |

| Skin prick test positive (n) (%) | 15 (13%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.37 |

The mean percentage of total eosinophil count of patients was similar to that of the control group. The mean level of IgE was significantly higher in children with FMF than controls (136±268, 87±201, respectively; p values <0.05). The percentages of skin prick test positivity were similar for both patients and controls (13% and 8.2%, respectively; p>0.05).

DiscussionFMF is the most common autoinflammatory periodic fever syndrome. Although studies concerning pathogenesis had been a point of interest for a long time, the inflammatory mechanisms bringing about the clinical symptoms have not been clarified yet. Even though the mutant pyrin was accepted as the promoter of inflammation, the pathophysiology seems to be more complex. The role of Th1 and Th2 cells in FMF had been assessed for so long and increased IFNγ concentrations at the peripheral blood of FMF patients were accepted to be pertinent with Th1-mediated inflammation.15,16

Atopy is a tendency to become sensitised and produce IgE antibodies in response to ordinary exposures to allergens. Atopic disorders are thought to be driven by a Th2 response. By exposure to aeroallergens, Th cells are propagated to differentiate towards Th2 subtype and induce B cells to secrete IgE. Previously, highly activated Th2 cells are thought to decrease the Th1 differentiation. It had been also postulated that the predominance of Th1 response may be a possible protector against atopic diseases.10,17

However, a new scenario is on the agenda. Due to changing concepts regarding T lymphocyte subgroups, the Th1/Th2 paradigm is de-escalating its significance. T cell subpopulations other than Th1/Th2, in particular Th17 and T reg cell lineages, were shown to be critically involved in the pathogenesis of periodic fever syndromes. Th17 derived cytokines were accepted to be important regulators of neutrophilic inflammation. IL-17 that is produced mainly by Th17 cells is involved in inducing and mediating pro-inflammatory responses. Recent studies also support the hypothesis that Th17 cells are also one of the key players of allergic inflammation and asthma. This cell subpopulation may be accepted as the major evidence of interaction between innate and adoptive immunity.20

While planning this study, in contrary to previous studies our hypothesis was that there should not be a strict antagonism between FMF and atopy, hence the relation between Th1/Th2 is not a simple but a more complex entity. There are only few studies published regarding atopy and related symptoms in FMF patients. Sackesen et al. questioned children with FMF for asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis and although there was no significant difference regarding the frequency of asthma and eczema, they found decreased prevalence of atopy among FMF patients.10 They concluded that FMF seems to be a protective disease against the development of atopic sensitisation and allergic rhinitis.10 Yazıcı et al. found decreased frequency of atopy both in patients with FMF and with Behçet's disease.11 According to our data, the prevalences of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma in the patient group were similar to the control group. A recent study from Turkey investigating the frequency of atopy in children and adolescents with FMF found similar results to our study.18 In that study, the rate of physician-diagnosed asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis were similar in both FMF patients and controls. The authors also pointed to the presence of a more complex explanation rather than the Th1/Th2 paradigm.18

Zhang et al. studied atopy and systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SoJIA) as two dysregulated immune system diseases, they found that the presence of atopy worsens the outcome of SoJIA. As opposed to the expected, the low frequency of allergic diseases in patients with SoJIA could not be displayed.19 As in our study, this prospective study showed that the Th1/Th2 hypothesis was too simplistic to explain the interaction between atopy and SoJIA. Th17 cells show a linkage and possess an intrinsic plasticity allowing them to shift to Th-1 like and Th-2 like cells according to the environmental triggers.7,9 Therefore, we conclude that there is not a proven antagonistic relationship between atopic diseases and familial Mediterranean fever. Understanding the pathophysiological role of new cell types will change the common previous beliefs about the certain distinction between the pathways involved in two dissimilar diseases.

Key messages- 1.

Children with familial Mediterranean fever do not have an increased allergy prevalence.

- 2.

Only involvement of Th1/Th2 cells cannot explain the pathophysiology of these diseases.

- 3.

Th17 response has a heightened importance as a connection between auto-inflammatory and auto-immune diseases.

The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors has any conflict of interest.