Wheezing is a very common problem in infants in the first months of life. The objective of this study is to identify risk factors that may be acted upon in order to modify the evolution of recurrent wheezing in the first months of life, and to develop a model based on certain factors associated to recurrent wheezing in nursing infants capable of predicting the probability of developing recurrent wheezing in the first year of life.

MethodsThe sample was drawn from a cross-sectional, multicentre, descriptive epidemiological study based on the general population. A total of 1164 children were studied, corresponding to a questionnaire response rate of 71%. The questionnaire of the Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes (EISL) was used. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the probability of developing recurrent wheezing and to quantify the contribution of each individual variable in the presence of the rest.

ResultsInfants presenting eczema and attending nursery school, with a mother who has asthma, smoked during the third trimester of pregnancy, and did not consume a Mediterranean diet during pregnancy were found to have a probability of 79.7% of developing recurrent wheezing in the first year of life. In contrast, infants with none of these factors were seen to have a probability of only 4.1% of developing recurrent wheezing in the first year of life. These results in turn varied according to modifications in the risk or protective factors.

ConclusionsThe mathematical model estimated the probability of developing recurrent wheezing in infants under one year of age in the province of Salamanca (Spain), according to the risk or protective factors associated to recurrent wheezing to which the infants are or have been exposed.

Wheezing, because of its tendency to recur, is one of the most common problems in the first months of life.1 The lack of specificity of the clinical manifestations, the variability of patient response to the existing treatments, and the association between wheezing and viral infections in this age group2 can have a significant impact upon the quality of life of both the infant and the family,3 with an increase in the use of healthcare resources,4 and an important economic impact.5

Many studies have addressed wheezing in infants, although most have focused on viral causes6–8 or on the influence of allergies.9,10 In turn, some authors have related wheezing to obstetric antecedents,11 early exposure to certain allergens,12 immune alterations caused by certain environmental exposures13,14 or the administration of certain medications during pregnancy.15

A group of Spanish coordinators of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC)16 developed the International Study on Wheezing in Nursing Infants (Estudio Internacional de Sibilancias en Lactantes (EISL)) to determine the prevalence of wheezing, its severity and risk factors in the first 12 months of life.17 These and other previous as well as subsequent studies have indicated that there are other factors apart from viral infections that might interact and condition the presence of recurrent wheezing (RW) in the first months of life, such as infant gender, attending nursery school, diet, characteristics of the home, pets, maternal diet during pregnancy, smoking, the presence of siblings, pneumonia, etc.1,18–21 The objective of the present study was to identify risk factors that may be acted upon in order to modify the evolution of recurrent wheezing in the first months of life. In this respect, a predictive model was developed, based on certain risk or protective factors, capable of predicting the probability of developing recurrent wheezing in the first year of life – with the evaluation of variations in probability according to changes in one or more factors.

Material and methodsStudy designA sample corresponding to one-year-old infants born in the province of Salamanca, Spain between 1 June 2008 and 31 May 2010 was drawn from a cross-sectional, multicentre, descriptive epidemiological study based on the general population.

Study subjectsThe EISL questionnaire has been validated in Spain and Latin America,22 and the results were found to be equivalent to those reported for other questionnaires developed for use in large studies.23 The questionnaire comprises 118 items with questions referring to demographic characteristics, the home and surroundings of the infant, the eating habits of the mother during pregnancy, disease and medications used, complications at delivery, family antecedents of atopic disorders, a history of eczema in the infant, wheezing and its characteristics and severity, and the treatments provided. The questionnaire was distributed among the parents of infants visiting all the primary care centres (urban and rural) in the province of Salamanca for the regular scheduled visit at 12 months of age and for triple viral vaccination at 15 months of age. However, in the case of 15-month-old infants, the parents were informed that the questions all referred to the first year of life only.

Infants with incomplete or incorrectly completed questionnaires were excluded, as were those in which the number of wheezing episodes was not known, and those cases in which the parents failed to give consent. A total of 1164 children were studied, corresponding to a questionnaire response rate of 71%.

DefinitionsWheezing was considered to have occurred when the parents gave an affirmative answer to the following question: “Has your child experienced wheezing or whistling sounds in the chest in the first 12 months of life?” Recurrent wheezing (RW) in turn was defined as three or more wheezing episodes in the first year of life.

Childhood eczema was defined when the parents gave an affirmative answer to the following question: “Has your child developed itchy red areas on the skin that come and go anywhere on the body except around the mouth, nose and area covered by the diapers?”

The questionnaire was not specifically designed to determine whether the mother had followed a Mediterranean diet during pregnancy. Nevertheless, the diet was considered to have been followed when the mother gave affirmative answers to the following questions referring to eating habits: “Do you eat olive oil and white or blue fish three or more times a week? Fruit or fruit juice three or more times a week? Fresh or cooked vegetables or salad three or more times a week? Legumes or cereals (bread) or pasta three or more times a week? Eggs two or more times a week? Milk or yoghurt three or more times a week?”

Study variablesThe primary study variable was the presence or absence of recurrent wheezing during the first year of life, and was used as the dependent variable in the statistical association analyses.

Data analysisThe questionnaires were scanned (Fujitsu M4097D) using Remark Office Optical Mark Recognition (OMR) v6 software (Principia products, Paoli, PA, USA).

Qualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while the mean and standard error were calculated in the case of quantitative variables.

Statistical significance of the association of qualitative variables was assessed using the chi-squared test and odds ratio (OR), with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

The statistical analyses were made with the SPSS version 18 statistical package. Calculation of odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals was carried out using a Microsoft Excel 2007 application.

Following univariate logistic regression analysis to identify the variables significantly (p<0.05) related to the presence of recurrent wheezing, a multiple logistic regression model was developed to establish the probability of recurrent wheezing and quantify the contribution of each variable in the presence of the rest. The results were synthesized in the form of classification trees constructed from the probabilities estimated by the model:

Ethical approvalInformed consent was requested from the parents before including the patients in the study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the area of Salamanca.

ResultsThe study included a total of 1164 infants, and presented a response rate of 71% (603 males (51.8%) and 561 females (48.2%)). The infant birth weight was 3030±770g, with a height at birth of 49.48±3.46cm.

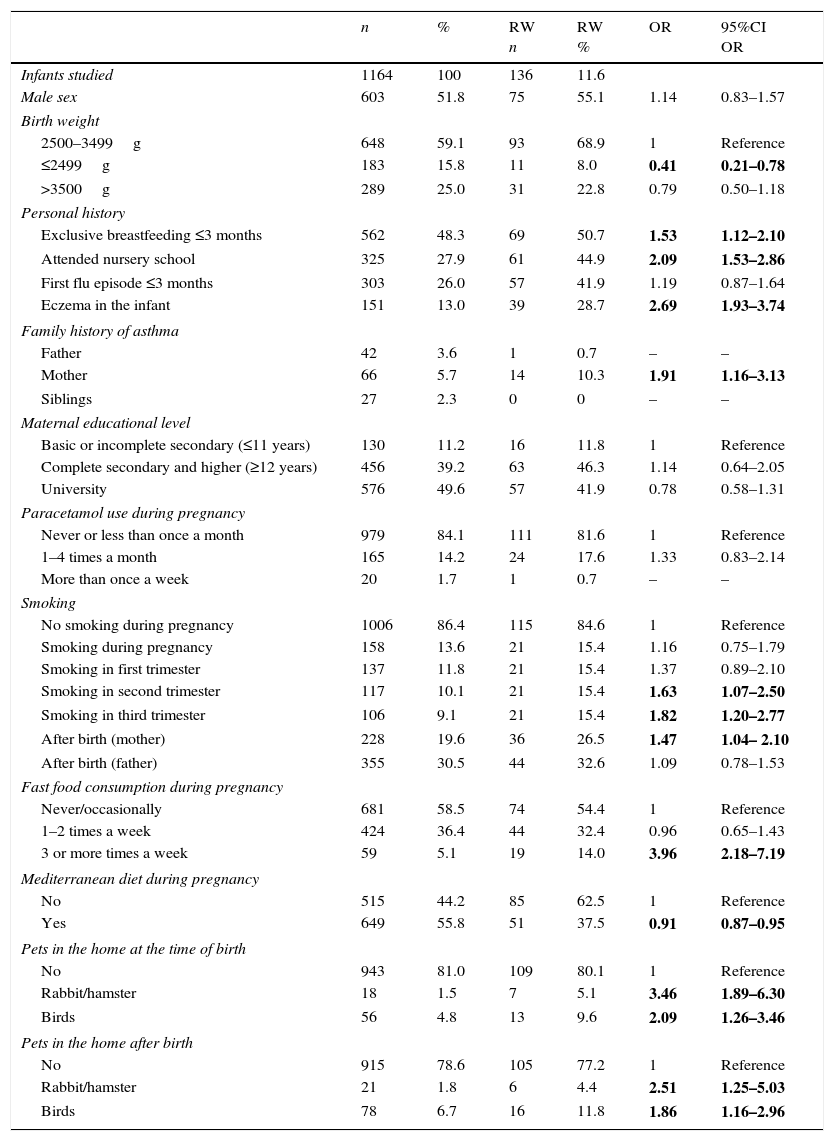

Table 1 shows the results referring to the risk factors studied in the infants that suffered recurrent wheezing (RW) in the first year of life, with the corresponding odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Association between risk and protective factors and recurrent wheezing (RW) during the first year of life. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals.

| n | % | RW n | RW % | OR | 95%CI OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants studied | 1164 | 100 | 136 | 11.6 | ||

| Male sex | 603 | 51.8 | 75 | 55.1 | 1.14 | 0.83–1.57 |

| Birth weight | ||||||

| 2500–3499g | 648 | 59.1 | 93 | 68.9 | 1 | Reference |

| ≤2499g | 183 | 15.8 | 11 | 8.0 | 0.41 | 0.21–0.78 |

| >3500g | 289 | 25.0 | 31 | 22.8 | 0.79 | 0.50–1.18 |

| Personal history | ||||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding ≤3 months | 562 | 48.3 | 69 | 50.7 | 1.53 | 1.12–2.10 |

| Attended nursery school | 325 | 27.9 | 61 | 44.9 | 2.09 | 1.53–2.86 |

| First flu episode ≤3 months | 303 | 26.0 | 57 | 41.9 | 1.19 | 0.87–1.64 |

| Eczema in the infant | 151 | 13.0 | 39 | 28.7 | 2.69 | 1.93–3.74 |

| Family history of asthma | ||||||

| Father | 42 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.7 | – | – |

| Mother | 66 | 5.7 | 14 | 10.3 | 1.91 | 1.16–3.13 |

| Siblings | 27 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | – | – |

| Maternal educational level | ||||||

| Basic or incomplete secondary (≤11 years) | 130 | 11.2 | 16 | 11.8 | 1 | Reference |

| Complete secondary and higher (≥12 years) | 456 | 39.2 | 63 | 46.3 | 1.14 | 0.64–2.05 |

| University | 576 | 49.6 | 57 | 41.9 | 0.78 | 0.58–1.31 |

| Paracetamol use during pregnancy | ||||||

| Never or less than once a month | 979 | 84.1 | 111 | 81.6 | 1 | Reference |

| 1–4 times a month | 165 | 14.2 | 24 | 17.6 | 1.33 | 0.83–2.14 |

| More than once a week | 20 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.7 | – | – |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No smoking during pregnancy | 1006 | 86.4 | 115 | 84.6 | 1 | Reference |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 158 | 13.6 | 21 | 15.4 | 1.16 | 0.75–1.79 |

| Smoking in first trimester | 137 | 11.8 | 21 | 15.4 | 1.37 | 0.89–2.10 |

| Smoking in second trimester | 117 | 10.1 | 21 | 15.4 | 1.63 | 1.07–2.50 |

| Smoking in third trimester | 106 | 9.1 | 21 | 15.4 | 1.82 | 1.20–2.77 |

| After birth (mother) | 228 | 19.6 | 36 | 26.5 | 1.47 | 1.04– 2.10 |

| After birth (father) | 355 | 30.5 | 44 | 32.6 | 1.09 | 0.78–1.53 |

| Fast food consumption during pregnancy | ||||||

| Never/occasionally | 681 | 58.5 | 74 | 54.4 | 1 | Reference |

| 1–2 times a week | 424 | 36.4 | 44 | 32.4 | 0.96 | 0.65–1.43 |

| 3 or more times a week | 59 | 5.1 | 19 | 14.0 | 3.96 | 2.18–7.19 |

| Mediterranean diet during pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 515 | 44.2 | 85 | 62.5 | 1 | Reference |

| Yes | 649 | 55.8 | 51 | 37.5 | 0.91 | 0.87–0.95 |

| Pets in the home at the time of birth | ||||||

| No | 943 | 81.0 | 109 | 80.1 | 1 | Reference |

| Rabbit/hamster | 18 | 1.5 | 7 | 5.1 | 3.46 | 1.89–6.30 |

| Birds | 56 | 4.8 | 13 | 9.6 | 2.09 | 1.26–3.46 |

| Pets in the home after birth | ||||||

| No | 915 | 78.6 | 105 | 77.2 | 1 | Reference |

| Rabbit/hamster | 21 | 1.8 | 6 | 4.4 | 2.51 | 1.25–5.03 |

| Birds | 78 | 6.7 | 16 | 11.8 | 1.86 | 1.16–2.96 |

Statistical significance as risk factors for the development of RW in the first year of life was identified for: a briefer duration of exclusive breastfeeding (OR 1.53 (95%CI 1.12–2.10)), nursery school attendance (2.09 (1.53–2.86)), the presence of eczema in the infant (2.69 (1.93–3.74)), a history of asthma in the mother (1.91 (1.16–3.13)), the regular consumption of so-called fast foods during pregnancy (3.96 (2.18–7.19)), and the presence of certain pets (birds and rabbits/hamsters) both at birth and after birth (1.86 (1.16–2.96)). Although no correlation to smoking was found throughout pregnancy (1.16 (0.75–1.79)), on separately considering smoking in the different trimesters of pregnancy, an association was identified when the mother smoked in the second and third trimesters (1.63 (1.07–2.50) and 1.82 (1.20–2.77), respectively), and after delivery (1.47 (81.04–2.10)). In contrast, a lower birth weight (0.41 (0.21–078)) and consumption of the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy (0.91 (0.87–0.95)) were identified as protective factors.

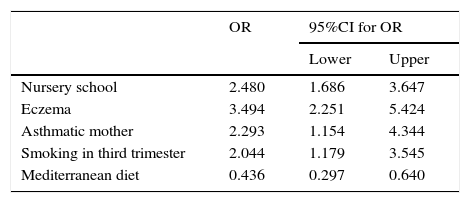

Taking into account the above findings, we developed the logistic regression model, considering all the aforementioned significant variables, as described in Material and methods. The results are shown in Table 2.

Variables showing statistical significance in the multivariate analysis. Estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| OR | 95%CI for OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Nursery school | 2.480 | 1.686 | 3.647 |

| Eczema | 3.494 | 2.251 | 5.424 |

| Asthmatic mother | 2.293 | 1.154 | 4.344 |

| Smoking in third trimester | 2.044 | 1.179 | 3.545 |

| Mediterranean diet | 0.436 | 0.297 | 0.640 |

The following variables were excluded from the model: exclusive breastfeeding ≤3 months (p=0.092); smoking in the mother during the second trimester (p=0.863); and current smoking in the mother (p=0.457). This means that after considering the variable smoking during the third trimester, the other two variables related to smoking did not contribute significant information, in the same way as exclusive breastfeeding.

Attending nursery school, presenting eczema, an asthmatic mother, and maternal smoking during the last three months of pregnancy were significant risk factors for RW. Mediterranean diet during pregnancy in turn exerted a significant protective effect against RW (see OR and 95%CI values in Table 2).

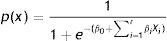

The model for estimating the probability of RW is expressed as follows:

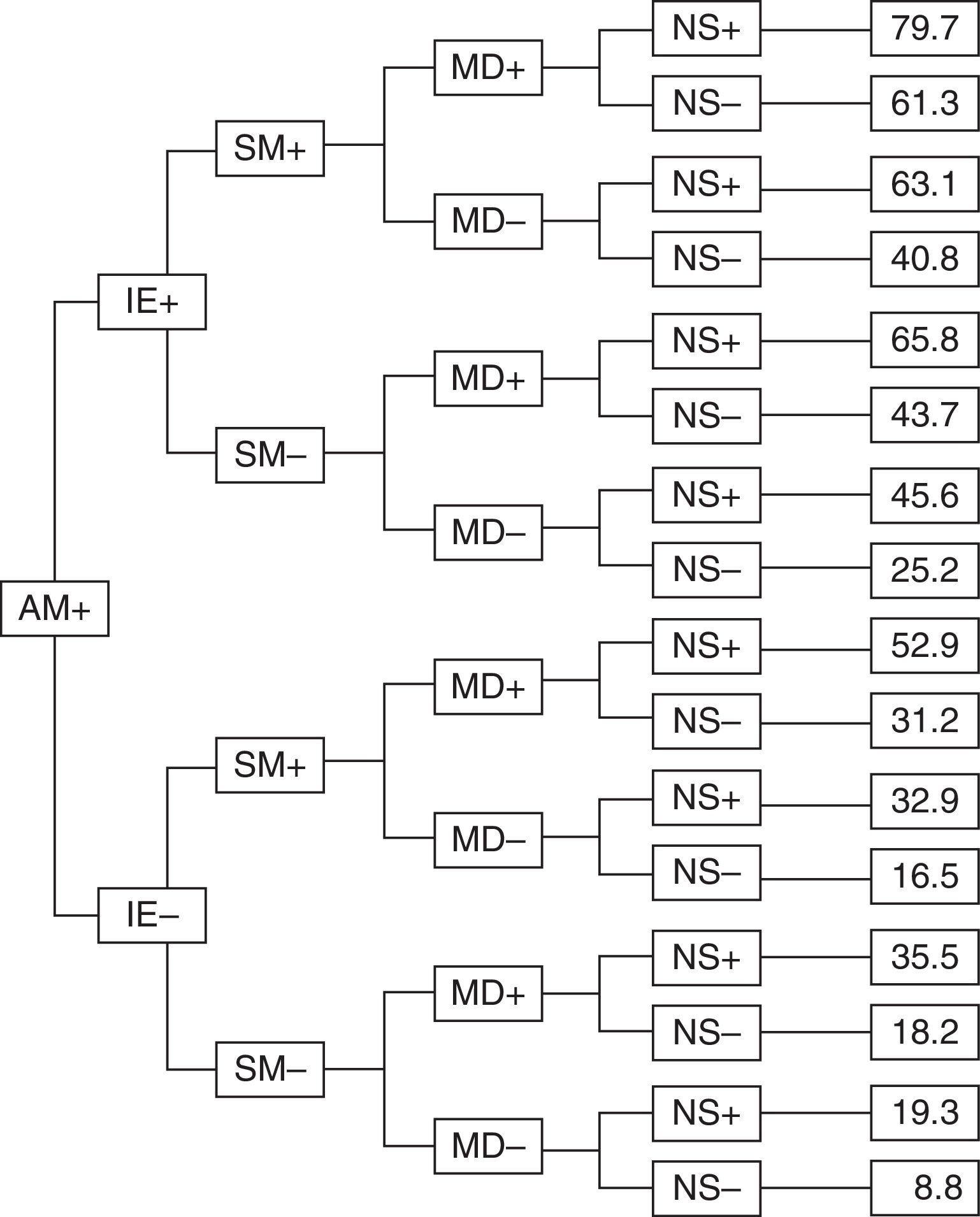

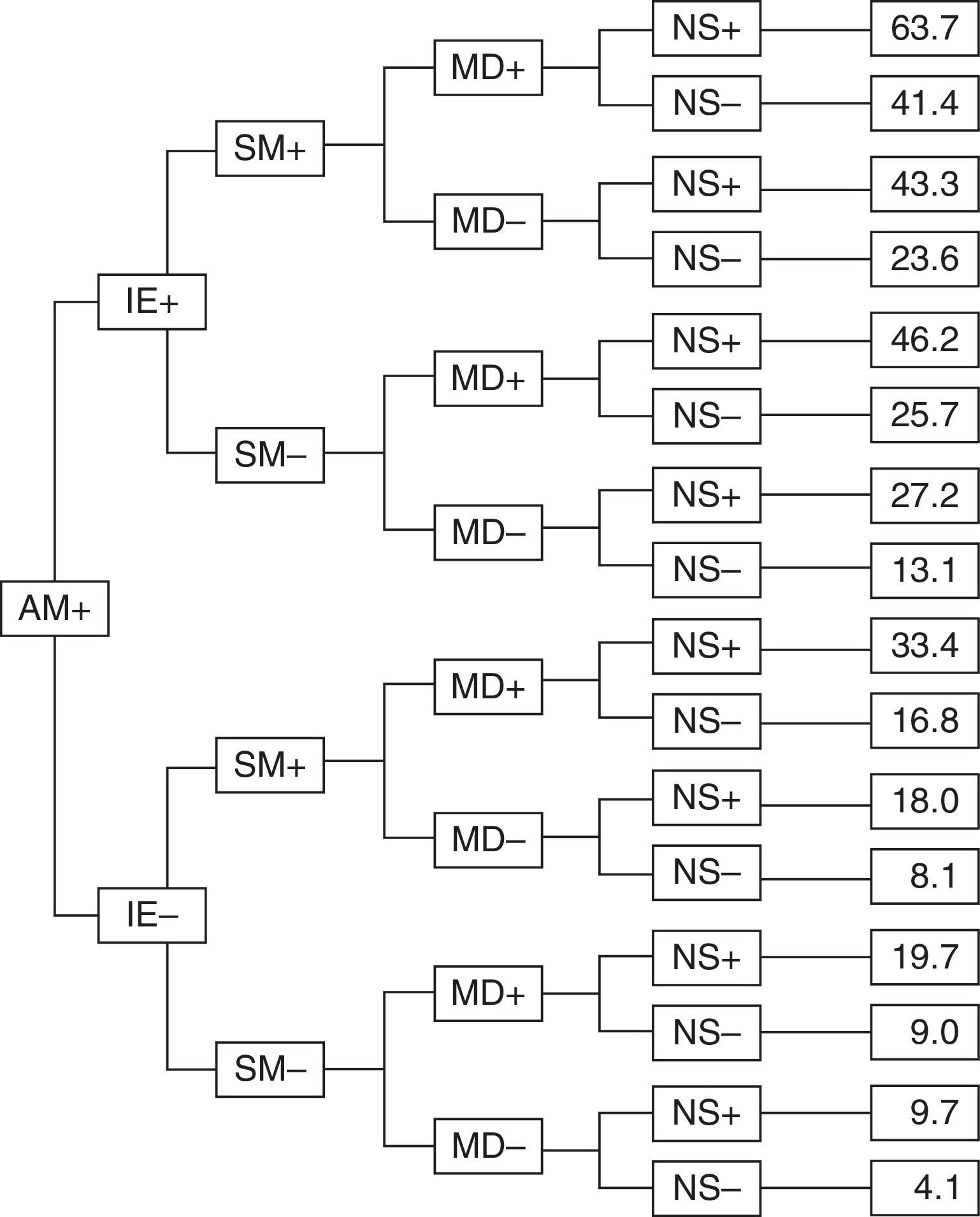

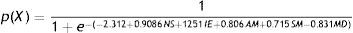

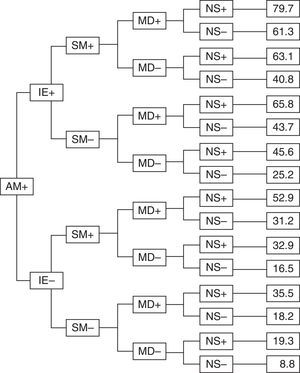

AM: asthmatic mother, IE: infant eczema, SM: smoking mother, MD: Mediterranean diet, NS: attended nursery school.Figs. 1 and 2 show the results in the form of classification trees (that of the first figure being based on whether the mother suffered asthma or not).

Classification tree with the different probabilities of developing recurrent wheezing during the first year of life, with the variables found to be significant in the multivariate analysis, for infants with asthmatic mothers. Abbreviations: AM: asthmatic mother, IE: infant eczema, SM: smoking mother, MD: Mediterranean diet, NS: attended nursery school.

Classification tree with the different probabilities of developing recurrent wheezing during the first year of life, with the variables found to be significant in the multivariate analysis, for infants with non-asthmatic mothers. Abbreviations: AM: asthmatic mother, IE: infant eczema, SM: smoking mother, MD: Mediterranean diet, NS: attended nursery school.

In this regard, infants presenting eczema and attending nursery school, with a mother who has asthma, smoked during the last trimester of pregnancy, and did not follow a Mediterranean diet during pregnancy were found to have a 79.7% probability of suffering recurrent wheezing (Fig. 1).

In contrast, infants with mothers presenting none of these factors had a mere 4.1% probability of suffering recurrent wheezing (Fig. 2).

The mathematical model developed exhibited a true-positive rate of 81.48% and a specificity of 99.5%. Overall, the correct classification rate was 89.7% (efficacy of the model). Both the false-positive and false-negative rates were low (10.11% and 18.52%, respectively).

DiscussionAsthma is the most common chronic disease in childhood, and wheezing is often detected in the first months of life. This high prevalence suggests that there are different subgroups of infants exhibiting different inflammatory responses to a range of triggering factors, and this has led to many studies on the subject in recent years.

In this sense, many authors have examined the presence of wheezing in nursing infants. The recently published data of the EISL,1,18,20,21,24,25 as well as those of our own group,19 have revealed great variability in the statistical significance of the risk factors for wheezing and RW in different parts of the countries and in different centres.26

Some authors have investigated the relationship between certain nutrients during pregnancy and the development of RW or asthma in the first months of life. In this respect, Miyake et al.27 found an increased intake of dairy products, calcium, vitamin D, alpha-linolenic acid and docosahexaenoic acid during pregnancy to be associated with a decrease in RW at 16 and 24 months of age. Castro et al. in turn observed an association between olive oil consumption during pregnancy and a lesser incidence of RW in infants under one year of age.28 In our study we found a statistically significant relationship between consumption of a Mediterranean diet on the part of the mother during pregnancy and the development of RW in the infant. The association was strong enough to enter the predictive model. Such an association has also been reported in older children,29 in some cases relating a Mediterranean diet and obesity.30

The relationship between RW in infants and a family history of atopy is known, although our group only found an association between RW and maternal asthma – in coincidence with the observation of other authors.28,31

Regarding breastfeeding, and in concordance with other investigators,18,32–35 we observed a lesser proportion of RW among the infants exclusively breastfed for more than three months, compared with those infants breastfed for three months or less – although the model suggests this protective effect against infections of exclusive breastfeeding during the first year of life to be partially cancelled when the infants attend nursery school, since the latter factor prevails due to its strong influence in the final model.

A notable observation in our study was the association between low birth weight and a lesser incidence of RW. These results must be viewed with caution, however, since only 11 infants with RW weighed less than 2500g at birth, and none weighed less than 2000g at birth.

Although many studies have described statistically significant correlations to different risk or protective factors,36–39 our review of the literature yielded no studies relating multiple factors in the context of a predictive model of RW in infants according to exposure to risk or protective factors as was done in our study.

Based on the proposed model, our study in Salamanca has shown that infants with all the risk factors included in the model have a 79.7% probability of developing RW, while those infants that present no such factors have a risk of only 4.1% of developing RW. However, the model also describes the probability of suffering RW with any other combination of risk factors. The variables are represented in the model on a dichotomic basis: 0 (absent) or 1 (present). As an example, if the mother was asthmatic, the infant suffered eczema, the mother smoked during the third trimester of pregnancy, the mother followed a Mediterranean diet, and the infant did not attend nursing school, the probability of suffering RW dropped to 40.8% (i.e., a reduction of 38.9%) (Fig. 1).

All the possible alternatives, with their respective probabilities, according to whether the mother suffered asthma or not, are reflected in Figs. 1 and 2.

As has been commented above, the results published by the EISL show great variability.1,18–21,24 The mathematical model is based on the assumption that the factors which may enter the model vary according to the centre, country or geographical zone involved. In this regard, the proposed model must be adjusted to the results obtained in each zone, and future genetic studies will probably afford more precise information capable of explaining the great variability of the results obtained in the different geographical settings in which the EISL has been carried out.

As possible limitations of our study, mention must be made of the fact that the data were supplied by the parents on answering the EISL wheezing questionnaire, rather than by the attending paediatricians – although the mentioned questionnaire has been duly validated.22 On the other hand, when there were doubts regarding some item of the questionnaire, the parents were called by telephone or the reference paediatrician was consulted. It must also be noted that this is a cross-sectional study, and seasonal variations due to the relationship between RW and viral infection in this particular age group may have constituted a confounding factor – particularly in the winter months. This limitation was minimized by including infants born in all seasons of the year during a period of two years.

Lastly, the main strong points of the study are its sample size based on the general population, and the fact that infants from all primary care centres (both urban and rural) in the province of Salamanca were included, with the inherent cultural and socioeconomic differences involved.

The present study has allowed us to identify different risk or protective factors capable of interacting with each other, and which can determine whether or not RW will develop during the first year of life in the population studied. It would be important to conduct a prospective study based on the data of the EISL, with a view to designing a model for calculating the probability of suffering RW in a given population depending on the risk or protective factors to which it is exposed.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Financial supportThis project has received financial support from the Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y León, Spain. GRS 287BA/08.

A grant was received from the Fundación Ernesto Sánchez-Villares of the Sociedad de Pediatría de Asturias, Cantabria, Castilla y León.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.