Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood in industrialised countries. T helper-2 (Th-2) cells, mast cells and eosinophils have a role in inflammation of asthma. Recently it was shown that platelets also play a role in asthma. Mean platelet volume shows platelet size and reflects platelet activation.

ObjectiveThe aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate levels of mean platelet volume in asthmatic patients during asymptomatic periods and exacerbations compared with healthy controls.

MethodsThe study consisted of 100 asthmatic patients (male/female: 55/45, mean age: 8.2±3.3) and 49 age and sex matched healthy children as a control group.

ResultsMean platelet volume values of asthmatic patients during asymptomatic period were 7.7±0.8fL while mean platelet volume values in asthmatics during exacerbation were 7.8±0.9fL. Comparison of mean platelet volume values of asthmatic patients and healthy controls both in acute asthmatic attack and asymptomatic period showed no difference (p>0.05). Comparison of mean platelet volume values at asthmatic attack and asymptomatic period also had no difference (p>0.05). The presence of atopy, infection, eosinophilia, elevated immunoglobulin E, and severity of acute asthmatic attack did not influence mean platelet volume values.

ConclusionThe results of our study suggest that mean platelet volume values may not be used as a marker in bronchial asthma, although prospective studies with larger number of patients are needed to evaluate the role of mean platelet volume in asthma.

Asthma is a worldwide problem with an estimated 300 million affected individuals.1 The prevalence of asthma is increasing, especially in children and it is the most common chronic disease of childhood in industrialised countries.2 Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways which involves several inflammatory cells and multiple mediators resulting in characteristic pathophysiological changes. Inflammatory cells such as mast cells, Th2 cells and eosinophils are defined well in the asthmatic airway. Platelet activation was demonstrated in asthma for a number of years. Clinical evidence has been supplemented with experimental data that platelets are important components of the inflammatory response. Activated platelets secrete multiple inflammatory factors such as chemokines, cytokines and coagulation factors and thus enhance the aggregation, adhesion, and thrombus formation. The induction of inflammatory mediators by activated platelets enhances also the recruitment of leukocytes including eosinophils, monocytes and neutrophils via platelet P-selectin.3 Platelets’ volume increases when platelets become activated. Larger platelets contain more dense granules and have higher thrombotic potential and are able to induct the inflammation. Mean platelet volume (MPV) reflects the platelet size. Platelet size is correlated with platelet function and activation. Therefore higher MPV levels predict platelet activity and thus intensity of inflammation.4 There is a lot of evidence showing that platelets play a role in both allergic and non-allergic inflammatory conditions. Changes of MPV values have been studied in many chronic inflammatory diseases. Increased MPV values are related to some chronic inflammatory conditions such as familial Mediterranean fever (FMF).5,6 To the best of our knowledge, there is no study evaluating the relationship between asthma and MPV. The aim of this study is to investigate whether the inflammatory response affects MPV values in childhood asthma.

MethodsPatientsCase records of the Pediatric Allergy Department of Dokuz Eylul University Hospital for the period January 2007 to June 2009 were screened for patients diagnosed with asthma retrospectively. Only complete blood count (CBC) values obtained from patients both during an asthmatic attack and during the asymptomatic period were included in the study. The demographical data of patients were extracted from the patient data system. Laboratory data were screened via hospital's computerised patient database. Sex- and age-matched healthy children who visited the “well-child outpatient clinic” for routine controls and who did not have any chronic illnesses constituted the control group. The CBC parameters of control group were also obtained from the same hospital computerised database.

The CBC analyses were performed by the Coulter analyser, which was checked every month by the central laboratory. Blood samples were collected in standard tubes, which contained EDTA. The reference values for MPV ranged between 7.0 and 11.0fL.

Statistical AnalysesData were evaluated using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 13.0 (SPSS for Windows 13.0, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and by analysing descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation), comparing the means of quantitative data for dual groups using the Student t-test and paired t-test, chi square test. Pearson's correlation was used to evaluate the association between MPV and other laboratory values. p<0.05 was considered as significant. Data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD).

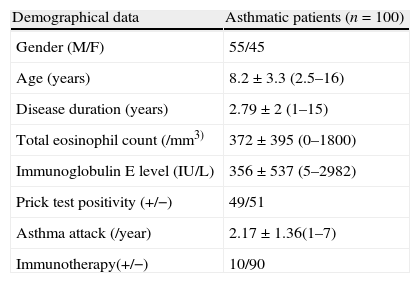

ResultsThere were 55 boys and 45 girls in the asthmatic group, while the healthy control group was of 22 boys and 27 girls. The mean age of the asthma patients was 8.2±3.3, while that of the controls was 9.1±2.6 years. No significant difference was found between asthmatic patients and the control group in terms of age (p=0.078) and gender (p=0.991). Clinical characteristics of the asthmatic children are shown in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of asthmatic children.

| Demographical data | Asthmatic patients (n=100) |

| Gender (M/F) | 55/45 |

| Age (years) | 8.2±3.3 (2.5–16) |

| Disease duration (years) | 2.79±2 (1–15) |

| Total eosinophil count (/mm3) | 372±395 (0–1800) |

| Immunoglobulin E level (IU/L) | 356±537 (5–2982) |

| Prick test positivity (+/−) | 49/51 |

| Asthma attack (/year) | 2.17±1.36(1–7) |

| Immunotherapy(+/−) | 10/90 |

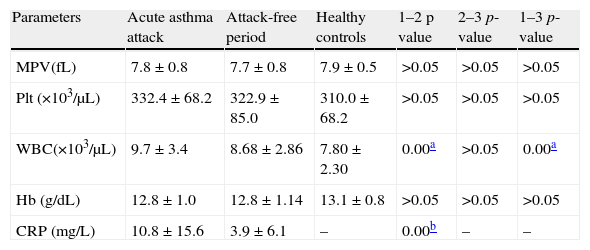

Mean platelet volume values of asthmatic children during an asthmatic attack and during the asymptomatic period were compared with MPV values of healthy children. Comparison of MPV values in asthmatic patients and healthy controls both in an acute asthmatic attack (p=0.434) and asymptomatic period had no statistically significant difference (p=0.110). Comparison of MPV values in asthmatic patients in an asthmatic attack and in the asymptomatic period also had no statistically significant difference (p=0.755) (Table 2).

Comparison of laboratory parameters between patients during asthma attack (group 1), attack-free period (group 2) and healthy controls (group 3).

| Parameters | Acute asthma attack | Attack-free period | Healthy controls | 1–2 p value | 2–3 p-value | 1–3 p-value |

| MPV(fL) | 7.8±0.8 | 7.7±0.8 | 7.9±0.5 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Plt (×103/μL) | 332.4±68.2 | 322.9±85.0 | 310.0±68.2 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| WBC(×103/μL) | 9.7±3.4 | 8.68±2.86 | 7.80±2.30 | 0.00a | >0.05 | 0.00a |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.8±1.0 | 12.8±1.14 | 13.1±0.8 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 10.8±15.6 | 3.9±6.1 | – | 0.00b | – | – |

Plt, platelet; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, haemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

The presence of atopy, infection, eosinophilia, elevated IgE, severity of asthmatic exacerbation did not influence MPV values (p>0.05).

DiscussionThis study demonstrated that MPV values in asthmatic children both during an asthmatic attack and during the asymptomatic period had no statistically significant difference compared to the healthy control group. Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was found between mean MPV values in asthma exacerbation and asymptomatic period.

The function of platelets is well known in haemostasis but also platelets are fully functional cells concurrently with haemostasis. Platelets have the ability to undergo chemotaxis, releasing various important mediators, expressing adhesion molecules on their surface and becoming activated in response to mediators released by other cells. Experimental evidence suggested that platelets have a role in each stage of asthma pathogenesis in development of bronchoconstruction, airway inflammation, airway remodelling and bronchial hyperresponsiveness.7 It is shown that platelet factor-4 and β-thromboglobulin levels as indicators of platelet activation increased in symptomatic atopic asthmatics platelets.8,9 Platelets of asthmatic patients respond to thrombin or platelet activating factor challenge by expressing higher amounts of P-selectin on their surface compared to healthy individuals.10 P-selectin expressing platelets prime eosinophil adhesion to the endothelium in atopic asthmatics.11 Moreover, a larger proportion of platelets expressed the high affinity receptor for IgE in asthmatic subjects.12 In the light of this evidence, platelet activation may be an important component of atopic and non-atopic asthma, especially in an asthmatic attack.7

Mean platelet volume values reflect the platelet size. Platelet size is determined at the level of progenitor cell (i.e. the megakaryocyte). Some studies reported that cytokines such as interleukin 3 (IL-3) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) influence megakaryocyte ploidy and can lead to the production of more reactive, larger platelets.13,14 IL-6 and IL-3 are the cytokines that are produced by Th2 cells.

Several studies were designed about MPV values in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as FMF, ulcerative colitis, Chron's disease, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondilitis.15,16 These studies suggested that MPV values were increased in FMF and decreased in the other diseases. Furthermore, it was suggested that increased MPV values are predictors of early atherosclerosis.17 In many chronic inflammatory conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis were related to enhanced risk of atherosclerosis.18–20 There were conflicting results in the association of asthma and atherosclerosis. Although some studies suggested that asthma enhanced the risk of atherosclerosis,21 others found speculative results about the association of asthma and atherosclerosis.22,23

In the current study we evaluated the relationship between asthma and MPV values. We suggested that asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder and platelets have a role in asthma. If MPV value is an indicator of inflammation, increased MPV values may be associated with asthma. However we could not find any difference in MPV values of asthmatics both in acute asthma and asymptomatic period. The limitation of our study is its retrospective design. Prospective studies performed in larger asthmatic populations may obtain further data about MPV values in asthma.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.