Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of zinc (Zn) deficiency. AE is the clinical phenotype of Zn deficiency and is characterized by pustular and bullous dermatitis with an acral and periorificial distribution, frequently associated with pustular paronychia, angular stomatitis, glossitis, generalized alopecia and diarrhoea.1–4

Initially the term AE was used to describe the congenital form. This genetic defect has been mapped to 8q24 and the defective gene identified as SLC39A4, which encodes the zinc transporter4 Zip4. Nowadays, AE is also associated with the acquired form of Zn deficiency resulting from impaired intestinal absorption due to gastrointestinal diseases or by poor consumption of the mineral.1–3 In this case it has been denominated as AE like (AEL) disease.

The diagnosis of AE is made by clinical presentation, dietary survey, laboratory tests, and histopathological findings (characteristic skin lesions). In some patients the differential diagnosis with other skin diseases is difficult and can generate delay in the correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

In this report we present an infant with AEL probably secondary to an inadequate dietary management due to suspicious atopic dermatitis (AD) related to cow's milk allergy.

CASE REPORTAn 11-month-old boy, the only child of non-related parents was born by normal delivery with satisfactory conditions, was exclusively breast-fed until he was 6months old. Then he was fed with cow's milk, orange juice, bean broth and vegetables. Two months later he developed diarrhoea, anorexia, alopecia, and a pruriginous, erythematous and maculopapular rash, distributed in face, axillar and inguinal regions, and buttocks. Treated topically with antifungal agents he did not experience any improvement.

At the age of 9months, skin lesions had worsened, became scaly and flaky, and spread into cervix, both arms, thigh, back of foot and malleolus, and despite using topical corticosteroids there was no improvement. Marked irritability, discrete alopecia, thin and friable hair was also observed at this time. His serum specific IgE to whole CM was positive, a CM free diet was initiated and a 15 % non-fortified soybean extract, with 5 % oat, was introduced.

Although he was on a restrictive diet, lesions worsened and spread with predominance of vesicles and pustular bullae, associated with anorexia, failure to thrive, and diarrhoea, that motivated his hospitalization twice. Oral lesions worsened food acceptance, especially of solid foods. Negative coagulase Staphylococcus was cultivated from the lesions and he was treated with systemic antibiotics and anti-histamines, and topical corticosteroids. At this time he was 11months old and was referred to our service.

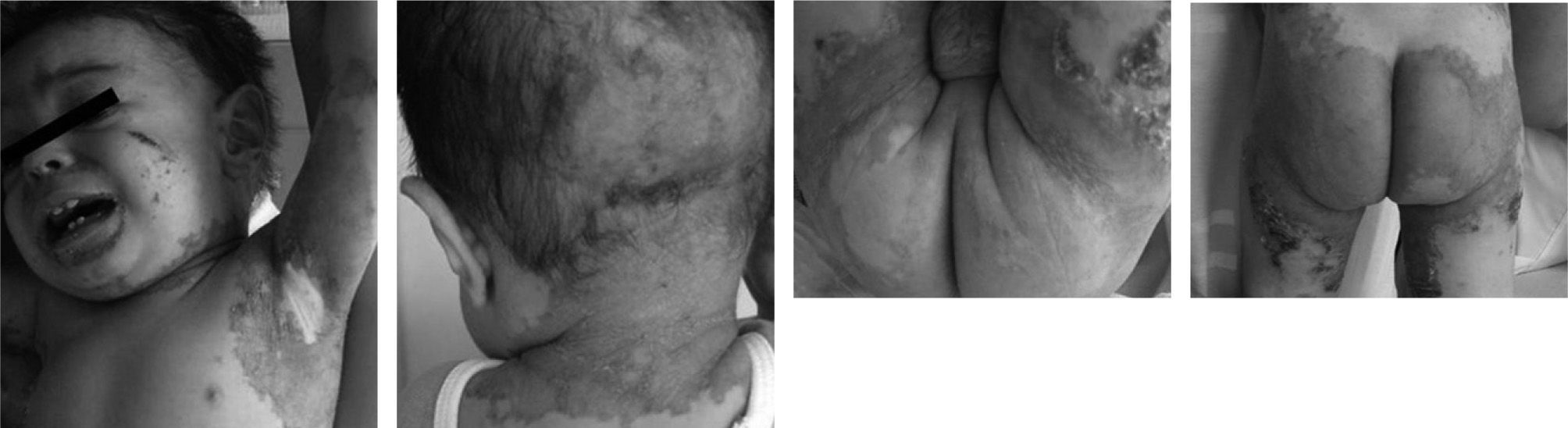

At his first clinical evaluation the patient was afebrile and irritable; his weight was 8.1kg (below 3rd percentile NCHS) and his height 70.5cm (below 5th percentile NCHS) characterizing him as a mildly malnourished infant.5 He presented with widespread erythematous scaly lesions distributed not only on the periorificial and acral area, but also on the buttocks, thigh and both arms, back of hands and foot and in malleolus (fig. 1A, B, C, and D). His scalp hair was thin and fragile with alopecia in the cervix (fig. 1A and B). Respiratory, cardiovascular, abdominal, and neurological examination findings were unremarkable. There was no relationship between exposure to climate changes, exposition to aeroallergens, physical activity, any medicine or contactant. He had virus bronchiolitis, acute otitis media and tonsillitis at 4, 8 and 10months, respectively and two hospitalizations due to diarrhoea and skin lesions. His father is asthmatic and his mother has allergic rhinitis.

Laboratory evaluation showed normal levels of haemoglobin, haematocrit, platelets count, and serum levels of immunoglobulin (G, A, and M). The white blood cell count revealed leucocytosis with normal distribution. Serum specific IgE to alpha-lactalbumin was 0.38 KU/ml and was absent for casein and beta lacto-globulin (UniCap Phadia). The serum level of Zn was lower than 40 mcg/dL (normal range: 70 to 120); Erythrocyte zinc was 414 mcg/dL (normal range: 440 to 860) and the level of dismutase superoxide was 5.3 U/g Hb (normal range: 6.5 to 14.5).

Microscopic examination of the skin lesions showed scattered parakeratosis; pustule-vesicle lesions partially broken and with lymphocytes and neutrophils infiltration in supra basal and sub corneal layers; irregular acanthosis; and dermal perivascular infiltration with neutrophil and spongiosis.

After diagnosis, appropriate dietary counselling was instituted, including soybean infant formula and stimulus for meat (particularly bovine) ingestion twice daily. Zinc arginine quelate (2mg zinc/kg/day) was prescribed during 4months. Vitamin supplements, in the daily dose recommended for age and gender6 and ferrous sulphate (1mg/kg/day) were also introduced.

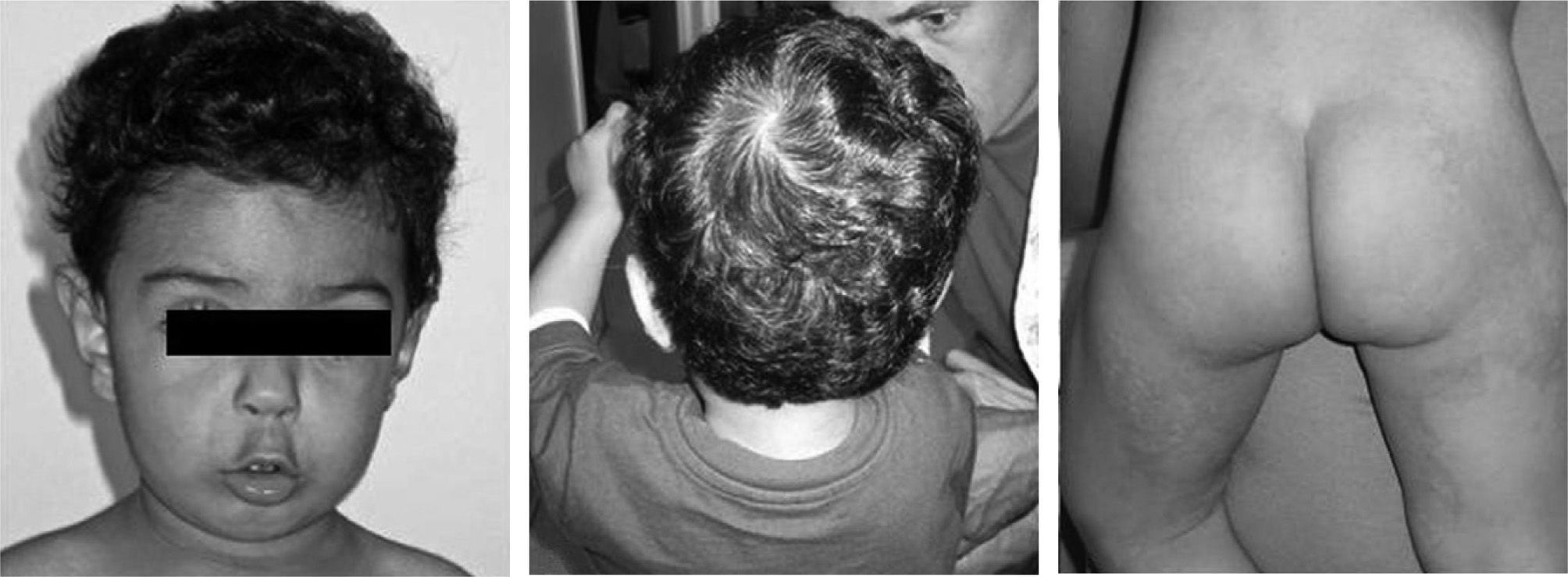

During the following weeks, the patient improved clinically and lesions disappeared almost completely. Two months later, after a negative double blind placebo controlled CM challenge, CM infant formula was introduced as was a free diet. During the next 6months weight and length increased 2.5kg and 11.5cm, respectively. Zn supplementation was then suspended and there was no patient harm (fig. 2).

DISCUSSIONZn has an important role in the generation and maintenance of several tissues, including the skin, cellular immune response and delayed hypersensitivity reaction, on growth and development and is also an essential cofactor for more than 200 enzymes, above all in carbohydrate, proteins and vitamin A metabolismo4,7,8

Although AE had been first reported in 1936 by Brandt1,9 it was not until 1942 that it was related with acral rash associated with diarrhoea by Danbolt & Closs and in 1973 it was related to Zn deficiency.1,2,7,9,10 Two forms of AE were identified: a) primary or congenital due to a genetic defect, autosomic recessive inheritance, with characteristic cutaneous lesions starting in early infancy,1,2,4,7,9,10 and b) secondary or acquired. The latter is also denominated AE-like (AEL) and is secondary to low ingestion or absorption of Zn, as in lactogenic acrodermatitis (breast milk deficient in Zn) or complementary food insufficient in Zn or with low bioavailability of Zn (phytate-rich diet, calcium-rich diet). Other causes of AEL are malabsorption syndromes (cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, chronic pancreatitis).1,3,4,7–13 Recently, two patients with food allergy with malabsorption associated and AEL were reported by Martin et al.14

Lesions of primary or secondary AE can simulate atopic dermatitis (AD). It is a chronic inflammatory and pruritic skin disease that affects adults and children, these mainly in the first year of life. AD is related with atopic sensitization, high levels of serum IgE, family history of atopy and is also associated, especially the severe forms, with food allergy.12–19 In general, young children with AD present lesions in scalp, malar and frontal regions with no involvement of buttocks and inguinal region.17–19 Acute phase lesions are extremely pruriginous erythematous papules, with serosanguineous exudation, vesicles or blisters and excoriations. Subacute lesions are dry erythematous excoriated papules.11,17

AE's lesions are vesicular and bullous, erythematous scaly plaques, seborreic or psoriasiform in acral and periorificial regions, hands, foot, knees, elbows and vertex.1–4,9,10 The triad dermatitis, alopecia and difficult to treat diarrhoea is present in only 20 % of cases.1 Zn deficiency is associated with: reduced healing; interference in growth and development; anorexia; delay of sexual maturation; hypogonadism; increased susceptibility of fungi or bacterial infections; gastrointestinal, psychiatric or ophthalmologic disorders; and mucosal lesions.1,2,4,7,9 In general, secondary infections are due to Candida albicans, Gram positive bacteria, and sometimes Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Klebsiella sp.1,4,7

The diagnosis of AE is based on clinical and dietary history, low levels of serum and/or erythrocyte Zn, although there are reports of patients with normal levels of Zn.1,4,9 Levels of dismutase superoxide and alkaline phosphatase, two Zn-dependent enzymes, can be reduced in serum.4,9,10

Complementary feeding is essential for adequate Zn nutritional status. It is well known that the concentration of Zn in breast milk declines sharply in the first few months of lactation and is independent of maternal Zn intake.20 In 9-12-month old breast-fed infants more than 90 % of Zn is derived from complementary feeding.21

The diet of the child we have reported, contained about 10 % of the recommended dietary allowance for Zn (3mg/day), being also insufficient in vitamins A, E, C, B1, B2, B6 and folate. It is also noteworthy that the diet was rich in phytates.

Zn supplementation as sulphate, gluconate or chelate (2mg Zn/kg/day), nutritional counselling and control of subjacent causes is the preconized treatment for AEL, especially in malnourished children.1,4,7,9,10,22 Behaviour alterations usually settle in 24 hours, skin lesions improve in between 4days and 6weeks, diarrhoea disappears in one week, and the alopecia improves in 1 to 3weeks.9,10

Our patient showed symptoms after 2months on CM feeding. As his skin lesions were severe and disseminated the diagnosis of AD was suspected. The identification of specific IgE to alpha lactalbumin (even at low levels), led to the erroneous diagnosis of DA secondary to CM allergy. Certainly, his Zn nutritional status was compromised and was further impaired with the inappropriate non-fortified soybean extract feeding. Furthermore, our patient had periorificial and oral lesions which are not present in AD.

The recovery of primary AE depends on permanent Zn replacement. In this case clinical improvement maintained with interruption of Zn supplementation and reintroduction of CM formula and appropriate nutritional counselling confirmed the AEL diagnosis.4,7,9

This report stresses again the importance and difficulty of the diagnosis of AEL. It also emphasizes the necessity of an appropriate nutritional orientation to prevent the development of severe nutritional deficiencies.